Live Encounters Magazine May 2021

Kathleen Mary Fallon most recent work is a three-part project exploring her experiences as the white foster mother of a Torres Strait Islander foster son with disabilities. The project consisted of a feature film, Call Me Mum, which was short-listed for the NSW Premier’s Prize, an AWGIE and was nominated for four AFI Awards winning Best Female Support Actress Award. The three-part project also includes a novel Paydirt (UWAPress, 2007) and a play, Buyback, which she directed at the Carlton Courthouse in 2006. Her novel, Working Hot, (Sybylla 1989, Vintage/Random House, 2000) won a Victoria Premier’s Prize and her opera, Matricide – the Musical, which she wrote with the composer Elena Kats-Chernin, was produced by Chamber Made Opera in 1998. She wrote the text for the concert piece, Laquiem, for the composer Andrée Greenwell. Laquiem was performed at The Studio at the Sydney Opera House. She holds a PhD (UniSA).

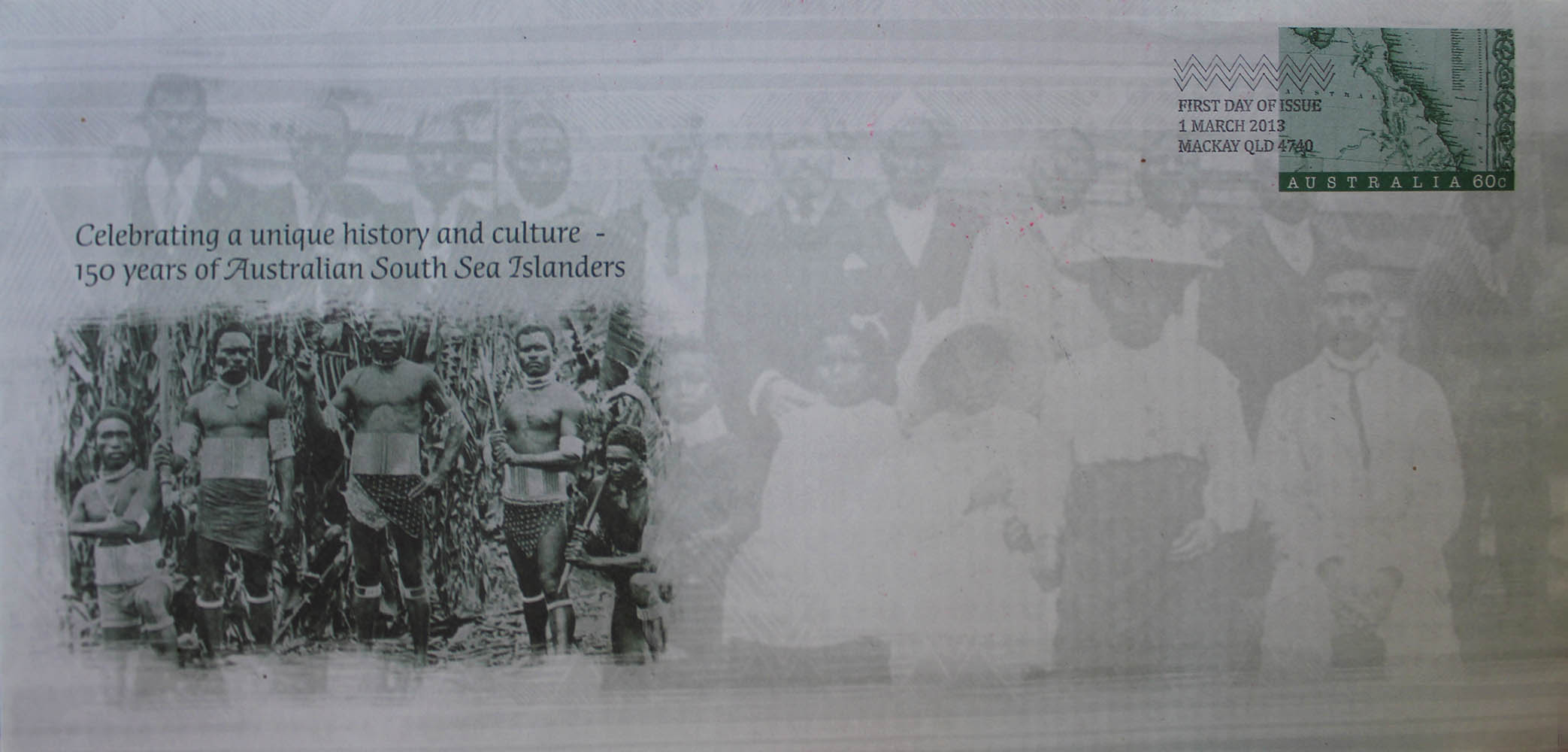

The Australian South Sea Islanders (ASSI):

Towards a Post-colonial Society?

I am five years old. I am at my grandfather’s sugar cane farm outside Bundaberg. He’s the Golden-syrup Man. I am wandering and wondering in the fields of rasping green cane. Wandering along beside me, on both sides, are stone walls. They are about the same height as I am and somehow they seem kindred. I can’t help caressing the warm grey-black orbs about the same size as my head. These are like friends with no eyes, no ears; no faces. I have to imagine them. I am taking a big risk because my mother, the White-sugar Princess, has warned me of the dangers lurking inside the walls. I imagine the yellow eyes of disturbed snakes; the rattle of the liquorice-black elephant beetles is a warning signal.

The Golden-syrup Man told me the walls had been built long ago by ‘Kanakas’ and I imagined they must have been mythical-magical beings to have constructed such beautiful walls. But what if these ‘Kanakas’ still lurked somewhere in all that cane? Were these the Boogeymen that the White-sugar Princess threatened me with if I was naughty? She said they were old Black men who walked the countryside with sugar bags over their shoulder in which they carried off naughty children. Was that them whispering in the rasping cane? Over half a century later I am engaged in fieldwork for a PhD trying to hear what they are whispering.

This is, again, the landscape in which I find myself, ‘a place where nature and culture contend and combine in history’[i] but this is still an infantile landscape of colonial phantasmagoria and fantasy; a landscape shared with these ‘Kanakas’. Is it possible to move out of phantasmagoria and fantasy and create a truly post-colonial landscape and how might this be achieved? Perhaps through knowing the thoughts, emotions and actions – the culture and hidden history – of these ‘Kanakas’, these ‘forgotten people’ for, as Ross Gibson says, ‘as soon as you experience thoughts, emotions or actions in a tract of land, you find you’re in a landscape.’[ii] Would this go some way to creating a post-colonial landscape in which their descendants, the Australian South Sea Islanders (ASSI) could also be known and their culture and contribution to the wealth – financial, cultural, social – of Queensland and Australia be acknowledged and respected?

This is what they were whispering about: a brief history

In August 1863 Robert Towns ‘brought’ the first sixty-seven ‘Kanakas’ to his Townsvale estate, near Beaudesert, to work on his cotton plantation. These ‘Kanakas’ came from Vanuatu (formerly New Hebrides) and the Loyalty Islands off New Caledonia. (The American Civil War was in progress and products such as cotton and sugar were at a premium.) The cotton didn’t do well in southern Queensland but, in the north, sugar did and the ‘Kanakas’ were sent north to work on the bourgeoning sugar industry. It was believed, at the time, that white workers couldn’t stand the rigours of a tropical climate. From the mid-nineteenth century until 1904, approximately 62,500 ‘South Sea Islanders’ were ‘brought’ to Australia mainly from the Solomons and Vanuatu and other Pacific islands as well as from Papua New Guinea, to ‘work’, as ‘indentured labour’, on these sugar plantations in the coastal regions of Queensland.[iii] By using the words, ‘South Sea Islander’, ‘brought’ and ‘work’, I have avoided the contested terms ‘Kanaka’, ‘blackbirded/kidnapped/recruited’ and ‘slavery’. These are much debated terms which raise points of disagreement within the ASSI community itself as well as amongst academics. A brief discussion of the hotly contested term, ‘Kanaka’, highlights some of these complex issues around history, memory and identity.

For some ASSI ‘Kanaka’ calls up the image of pitiful, enslaved victims in chains and loin cloths, ‘blackbirded’ by violence and trickery, forced from their islands, transported as human cargo in the filthy holds of sailing ships with inadequate food, ventilation or sanitary facilities, holds in which many died and were unceremoniously dumped at sea. This image is at odds with later generation’s pride in their ancestor’s resilience and determination to endure and make better lives for their descendants. The Australian South Sea Islanders are keenly aware of the political implications of the ways they are represented. I will use ‘Kanaka’ here, in quotation marks, to differentiate the old people from their Australian-born descendants who prefer the term Australian South Sea Islander and call themselves, ASSI (pronounced ‘ASSE’).

This chapter explores some of the strategies used by the ASSI in negotiating these fundamental and paradoxical situations around representation, remembrance and commemoration of their history and identity, and how these strategic negotiations have created, and continue to create, a landscape and unique culture, a culture that I believe can be considered postcolonial. To demonstrate this I focus on two major events in Mackay – the 2011 Recognition Day bus tour of ASSI heritage sites and the production, in 2013, of a ‘commemorative pilgrimage’ tourist guide to these same sites.

On arrival in Queensland the ‘Kanakas’ were sold, or delivered as per contract between plantation owners and ‘recruiters’, to sugar plantations all the way up the Queensland coast, where they then worked remorselessly in harsh and often lethal conditions. As Clive Moore has argued, ‘The death rate is a reprehensible 24 per cent of the total number of contracts and an even higher proportion of the individuals involved (around 30 percent).’[iv] They were ‘contracted’ (a thumb print on page of a contract they could not understand) as ‘indentured labour’ to work for three years after which they were to be returned to their home island. Alternatively, if they chose to remain in Queensland, they were classed as time-expired and could negotiate their pay rate and move more or less freely but were restricted to fieldwork.[v] There was also another class of ‘Kanaka’, the ticket-holder, who could work and travel anywhere and for any wage they could demand.[vi] (The Boogeyman myths probably had their origins in these two groups.)

The pay, rations and clothing for the ‘Kanakas’ were stipulated in the Polynesian Labourers’ Act 1868.[vii] Employers were to pay them £6 per year and were obliged to provide daily food rations, additional weekly rations of tobacco, salt and soap and an annual ration of clothing.[viii] Wages did rise over time; however, even twenty years later, they still fell well below those of Europeans: ‘the total amount paid to Europeans in 1888 … for wages and supplies (was) at the rate of 9 pounds for every 1 pound paid direct to kanakas,’ writes historian Tracey Banivanua-Mar.[ix]

The early ‘Kanakas’ constructed much of the infrastructure – including land clearance, building wells, wharves, roads, bridges – that enabled the sugar wealth of Queensland to grow. Among the first Acts passed after Federation in 1901 was the Immigration Restriction Act, part of the notorious White Australia Policy. Soon after, with the increasing tensions around the issue of ‘coloured’ labour and white workers’ rights, came the Pacific Island Labour Act which banned the importation of Islanders after the end of March 1906. It stipulated that all Islanders had to be ‘repatriated’ or forcibly deported, by the end of that year.[x] Through ASSI’s own activism and agency, however, a Royal Commission was established and the blanket law amended to allow some to remain.[xi] By 1906, around seven thousand Islanders were ‘repatriated’ and approximately two thousand remained. Most of those who remained were from the ticket-holder or time-expired groups.

The Islanders who remained have been subjected to repeated institutional and social discrimination, which has limited employment and economic development within the community. The ASSI are neither Indigenous nor migrant. They have often been ineligible for government benefits that Aborigines, Torres Strait Islanders or migrant groups have been eligible for. They have fallen through the cracks and the holes in the welfare net and yet they have survived in communities from the Tweed region of New South Wales and all the way up the coast of Queensland to Moa Island in the Torres Strait. According to Clive Moore’s estimates, ‘there are between twenty thousand and forty thousand’ ASSI in Australia today.[xii] The numbers are difficult to ascertain because some, with mixed heritage, identify administratively as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander on the Australian Census.

In the 1970s and early 1980s a renaissance of interest in the ASSI occurred in Australia and a flurry of media and academic activity brought this hidden history to public attention. This was partly due to the zeitgeist of the period, including the civil and indigenous rights movements, identity and solidarity politics, and the Black Power movement. The year 1978 saw the first significant coming-out onto the national stage for the ASSI with the airing of a three-part ABC radio documentary, ‘The Forgotten People’, produced by Matt Peacock for Broadband. This series brought the experiences of ASSI to wider public attention. Noel Fatnowna, a Mackay Elder, was extensively interviewed for the series, along with a number of other ASSI. The historian Clive Moore, a Mackay local, edited a book based on the series, which was published by the ABC. This was followed by his seminal study, Kanaka: A History of Melanesian Mackay in 1985. In 1989, Fatnowna went on to publish the first major ASSI memoir, Fragments of a Lost Heritage. Before this, in 1977, activist Faith Bandler had published the fictionalised biography of her father, Wacvie, followed by two other fictionalised biographies of family members over the next few years.

1967: The referendum and ASSI identity

Faith Bandler believed in Black Solidarity and in the 1960s worked with Federation for the Advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (FACCASI) towards the 1967 referendum which removed discriminatory clauses relating to Aboriginal peoples from the Constitution and also stipulated that Aboriginal peoples should be counted in the Australian Census. As a result the Federal Government eventually enacted legislation regarding land rights, discriminatory practices, financial assistance and preservation of cultural heritage for Aboriginal peoples but this did not apply to ASSI.

Faith Bandler’s experiences amply reveal the issues of identity with which the ASSI struggled, and continue to struggle; from all being blackfellas together suddenly divisions were created by identity politics. With the success of the referendum and the establishment of organisations such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Council (ATSIC) in 1990 she found herself excluded from the very organisations she had helped set up – because she identified as ASSI and not as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Following this exclusion she pursued her Islander ancestry by writing her fictionalised biographies and travelling to her father’s home island of Ambrym in Vanuatu. Complex issues around identity continue to permeate through the ASSI community. Some, for example, with Aboriginal or Torres Strait heritage are able to claim government support benefits, while those who insist on their ASSI identity are excluded from these benefits.

Again ASSI worked to deal with this new situation and through their tireless efforts achieved recognition from the Federal Government in September 1994 and from the Queensland State Government in August 2000. These governments recognised ASSI as a distinct cultural group and acknowledged past injustices as well as their significant contributions to the social, cultural and economic development of Queensland and Australia.[xiii] Each year, usually on 23 August, the ASSI celebrate Recognition Day as an important event in their social and cultural lives and the day has become very significant in the revivification of ASSI culture.

After 1980

What effect did the media interest and cultural activity of the 1970s and early 1980s have on this community and did it redress their sense of being ‘the forgotten people’ as they had hoped? Some answers to this question can be found in the activities of the ASSI community in the city of Mackay in central Queensland, and their relationship to the landscape and their ancestors.

Mackay has the largest population of ASSI in Queensland. Often referred to as the ‘sugar capital’ of Australia, the city is on the Pioneer River, approximately one thousand kilometres north of Brisbane. Sugar is the major industry, an industry built in the late nineteenth century by the Islanders’ labour. The whole area around Mackay – the endless acres of sugar cane, the scrubby hills, the banks of the creeks and river – hold deep resonance for ASSI who experience the landscape – infused, quite literally, with the blood, sweat and tears of their ancestors – quite differently from non-ASSI and Aboriginal peoples. Given the often violent and repressive past that their ancestors endured, Maria Tumarkin’s concept of ‘traumascape’ offers lucrative interpretive allusions appropriate to the landscape and its sites. According to Tumarkin, traumascapes are places … marked by traumatic legacies of violence, suffering and loss’, where:

the past is never quite over … spaces where events are experienced and re-experienced over time. Full of visual and sensory triggers, capable of eliciting a whole palette of emotions, traumascapes catalyse and shape remembering and reliving of traumatic events. It is through these places that the past, whether buried or laid bare for all to see, continues to inhabit and refashion the present.[xiv]

There are ‘visual and sensory triggers’ of ‘Kanaka’ presence everywhere in the Mackay area: graves – marked and unmarked – old wooden homes, rock walls, a historic hall, an ancient tree. Through their insistent remembering and persistent memorialising and through continued cultural, social and political labours these sites, which could so easily be silent, grief-filled traumascapes have been nurtured by the ASSI community and become sites of memory – nurturescapes rather than traumascapes – and provide the basis for healing, identity, and re/conciliation.

A question of identity

A question prominent in the 1970s and 1980s, and one still sometimes posed by the dominant, settler society, was: Do the ASSI have a culture? This question is also an issue for the ASSI. Many were told, and some even believed, that they had no culture of their own because they had lost their familial and cultural connections with their home islands. Also, their material culture – blady grass huts, kerosene tin furniture, hessian bag furnishings, cane trash cradles, gardens and so on – were impermanent and have largely disappeared. All they had were their ancestors stories, their oral history, and its association with the landscape. How could they make a culture out of these?

Noel Fatnowna, in his memoir, Fragments of a Lost Heritage, angrily and succinctly articulates this no-culture idea when he quotes what had been said to him: ‘ “You’ve got no customs, you’ve got nothing, you’ve got no brains.” ’[xv] The belief that ASSI have no culture is echoed in the 2002 documentary featuring Eddie ‘Koiki’ Mabo’s widow, Bonita Mabo, For Who I Am: Bonita Mabo. In this documentary she claims, and proclaims, her ASSI identity, which existed in the shadow of the strength of Eddie Mabo’s Torres Strait/Murray Islander cultural identity. Because she had lost her association with her home islands and tribal ancestry he’d say to her, ‘You don’t have a culture.’ [xvi]

Ross Gibson articulates the reasons for, and ramifications of, this belief that ASSI were a no-culture, ‘forgotten people’:

Most contemporary Australians feel compelled to deny the islanders any ancestry status in a comfortable modern federation … There is a tendency to ignore all the scrappy memories of past exploitations in Australia, to say that they are now so little in evidence that they have no bearing on the present. But because … their presence still resonates in descendants and community tales, in photographs and gravestones, and in the lingering dynasties of wealth, they are part of the world we take our living from.[xvii]

That the ‘Kanakas’ ‘presence still resonates’ and that the ASSI have created a culture and identity through the remembrance and memorialisation of their ‘presence’ is forcefully demonstrated in both events I discuss here. For the first, the 2011 Recognition Day bus tour of heritage sites, in which I participated, I describe my own and other’s responses to the tour and examine the memorialisation process for some of these sites. The collaborative and creative work I then did with members of the ASSI community to produce a ‘commemorative pilgrimage’ tourist guide was the basis for another bus tour in July 2013, which commemorated the 150th anniversary of the first ‘Kanakas’ arriving at Townsvale plantation. These events reveal each site as something of a text, alive with historical connotations and ramifications. The tourist guide and the bus tours were steps not only towards commemoration; they went beyond this, to healing. This is a story of history and trauma, but it is also one of healing, witnessing and collaboration. The sites are themselves artefacts, objects, machines of survival and an encyclopaedia of history and memory alive, still, with stories and the spirit of the old people, the ‘Kanakas’.

Christianity, melancholia and the post-colonial

The 2011 Recognition Day bus tour began with a commemorative service in the Farleigh Seventh Day Adventist Church beside the Farleigh Sugar Mill. Christianity has a long and complex relationship with the ASSI. As Gibson says, ‘The canefields around Mackay were spirited by a mélange of ‘theologies’ commingling Melanesian ancestor-worship and several Christian catechisms.’[xviii] The planters and mill owners often encouraged Christianity for their own political reasons, and yet the old people often embraced it wholeheartedly. Historian Kay Saunders, in ‘Workers in Bondage’, argues it is too simplistic to relegate the Christianity of the ASSI to the cynicism and expediency of the masters. ‘Christianity provided genuine spiritual and emotional comfort to committed Melanesians … The one area where Melanesians were made to feel important and worthy of regard was in the sphere of religion.’[xix]

Through their political agency, shrewd adaptability and survival strategies, the ASSI made the most of what was available to them. The importance of Christianity today, and its connection to respected ancestors, can be seen in a long and detailed letter-to-the-editor penned by the ASSI Elder, Rowena Trieve, published in Mackay’s The Daily Mercury in which she writes of her grandmother, Katie Marlla’s, Christian values. ‘Today, we, her descendants, reap the benefits of that choice. Practical Christianity … played a significant part in helping us Australian South Sea Islanders to assimilate and integrate.’[xx]

I suggest that partly as a result of their Christian values the ASSI as a community have overcome melancholia and are actively engaged in the hard emotional work of mourning and remembrance which has become memorialising; a constant ethical/political activity for them. According to Freud’s ‘Mourning and Melancholia’ the processes of mourning and melancholia are similar – feelings of loss, grief, dejection, lack of interest in the world, inability to love but, with melancholia, there is also a profound loss of self-regard and fear of poverty. With mourning there is an end and it is completed once the subject knows, through reality testing, that the object of mourning is dead whence normal ego activity and connection with the world resumes.[xxi] The ASSI know, very consciously, what they have lost and that their ancestors are dead and they have mourned them and now remember and honour them. They have also always been poor so poverty is not a fear but a reality they know how to deal with. They are reality-testers par excellence.

This is transformation work indeed, work which is also required of all Australians if we are ever to be truly post-colonial. Gibson suggests that the White Australia Policy can be interpreted, ‘as a melancholic refusal to allow differences into the definition of the society … a way to avoid the mourning’.[xxii] ‘The creation of the Commonwealth of Australia had been accompanied by a symbolic act of expulsion – the attempted deportation of Pacific Islanders.’[xxiii] The words of Marilyn Lake, Faith Bandler’s biographer, could be applied to all ASSI. ‘Faith’s very existence thus represented a defiance of White Australia.’[xxiv]

Gibson applies the concept of social melancholy to the colonial mentality. I would argue that in the events of Mackay’s 2011 Recognition Day and the events of the 150 commemorative year such as the ‘Uncle Cedric Andrew Andrew’s’ booklet and bus tour we see ASSI’s confrontation with, and refusal of, melancholia; their completed mourning and constant remembering through ritual and commemoration. In their quiet, determined and politically astute way they use the events to promote and progress their cultural and political agenda. In this it is possible to see their ‘struggle to translate racial grief into social claims’and how they construct ‘social meaning and its subjective impact at the site of racial injury.’[xxv] The events considered here will articulate the strategies with which ASSI confront the politics of amnesia, denial and neglect as they re-inscribe their history, ancestors, identity and continued presence into the public historical imagination and the dominant settler narrative; strategies such as the acceptance and mobalisation of what they see as their social and historical obligations to their ancestors and to the broader community through re/conciliatory practices.

The 2011 Recognition Day bus tour

In the early afternoon we boarded a bus and drove along River Street following the Pioneer River. We passed one of the oldest and most significant sites – the ancient Leichhardt Tree – under which the ‘Kanakas’ were assembled, sometimes in chains, to be dispatched to the various plantations. The tree has been desecrated any number of times and the trunk is covered in old and new scars from these attacks. Fresh scar marks were obvious from the most recent axe attack. Perhaps the inexplicable lack of signage at the tree is an attempt to avert such desecration.

We skirted the hills and drove along a dirt road that ran parallel to a line of trees, many of them coconut and mango trees. They shaded one of the many creeks where the ‘Kanakas’ had camped, lived and were often buried. The dirt road took us into Rowallan Park, which is owned and maintained as a Scout and Guide park. It is a significant area for the ASSI as there are a number of large, rock-mound, mass graves of Islanders there and also the last remaining section of what is known as ‘The Kanaka Trail’. The graves have been traditionally constructed with the heads at the west and feet facing east, to watch the rising sun, and there is a palm tree at the feet. The kilometre-long ‘Kanaka Trail’ is retained by stone-pitched reinforcement and is approximated three metres wide and has lasted, intact, through the Islanders expert craftsmanship, for over a century.

I returned to Rowallan Park a few days later after organising the visit with the non-ASSI caretaker, Bob Hodda, who generously spent the whole afternoon driving me around the park in his old Nissan flatback. Bob Hodda is in his eighties and has been involved in the scouting movement since his early teens. He has been protecting and maintaining the graves and the track for decades; keeping nature and man at bay.

Rowallan Park, protected as it has been, by the Scout’s ownership and Bob Hodda’s sensitivity and interest, from being ploughed under and turned into yet another field of sugar cane, is a very special and significant place. However, this small act of preservation only highlights the poignant fact that the same graves and trails would have been everywhere and it is only fortuitous that these few remnants remain.

The Recognition Day bus tour continued through Homebush along a road that ran parallel to the Pioneer River, which was curtained by what looked to me like nothing but mango trees and bushes. Yet there was excitement in the bus as coconut, bush lemon and pawpaw trees were spotted, and more stories emerged. This was the stretch of the river known as The Palms where many had grown up and where grandparents and parents had built homes and gardens. Pleasure was taken in the memories of happy homes and good fishing spots, of sandy beaches and swimming holes before the ASSI were moved to other housing in town and before the Dumbelton Weir, up stream, eroded all the sand.

Then a story was told of the recent reappearance of a long dead ancestor. There are many such stories in circulation. The ancestors aren’t dead and gone and forgotten but are a constant, powerful presence from ghostly visitations to profound forces of spiritual and cultural energy.

We drove on to Homebush and turned off the road just before the Cedric Andrew Bridge. Cedric Andrew was the oldest ASSI in the area. He was nearly 102 when he died in 2012 and his stories and memories were the basis for the organiser’s commentary. Here we stopped between two brick ruins. On one side was the brick stack from the original Homebush Mill and on the other what remained of a brick chimney from the Mill Office where the ‘Kanakas’ would line up to collect their pay and rations.

Then we crossed the Cedric Andrew Bridge over Sandy Creek to certainly the most important and revered site – the Homebush Mission Hall – where we alighted from the bus and inspected the charming, old-fashioned, humble hall, with its powerfully resonant political, religious and social history. It continues to be voluntarily maintained by local ASSI and non-ASSI. Built in 1892, on land granted by the Colonial Sugar Refinery, the hall was the location for the first meetings, in 1901, of the Pacific Islanders Association and it was here that they organised their political campaign against forced deportation. After inspecting the hall we were served an afternoon tea of scones and Golden Syrup.

Our last stop was Walkerston Cemetery nestled among endless cane fields. A green, freshly mown verge lies across from the official cemetery, between the road and the railway line along which the cane is carried to the mill. We stopped beside this green patch and were told that it was the site of many unmarked graves of ASSI ancestors who had been buried in ‘pagan ground’ outside the cemetery.

Landscape and oral history

As we headed back to Mackay I asked one of the women how visiting all these sites made her feel. Did it make her angry, frustrated, hurt? Her response typifies the ASSI attitude. She said that she was grateful to these old people because they had fought hard to stay in Australia and make a better life for their descendants and that nothing was to be gained in bitterness and negativity. She said she wanted her children to remember the truth of the past but not fill the memory with any hatred. It wouldn’t be what the old people wanted.

This long-held re/conciliatory stance is also a considered political and ethical response to the disappointments of the hopes held after the renaissance of interest in the late 1970s and 1980s. How did the ASSI reconsider this stance in the light of these disappointments in which the veracity of, and motivations for, the often traumatic testimonies of kidnapping, violence and slavery, gathered from Elders, were questioned and interpreted as expedient by some academics. Historian Patricia Mercer claimed, ‘that their forebears did not come willingly is an essential component of contemporary Melanesians’ attitudes to white Australia; so psychologically imperative is it that “blackbirding”, if it did not exist, would have to be created.’[xxvi] Likewise, historian Bob Reece attributed the strength of Australian South Sea Islanders’ views on kidnapping to political reasons: ‘the Kanaka descendants have a strong vested interest in repeating the horror stories (and there are plenty of them) about blackbirding and plantation life. What they are providing is not the raw stuff of history but an interpretation of history appropriate to the political needs of the moment.’[xxvii]

Much to the dismay of the ASSI, these interpretations found their way into a Queensland secondary school text book, Australian South Sea Islanders: a Curriculum Resource for Secondary Schools Secondary School as supposedly legitimate historical analyses, pitching history as a contested, texted domain. (This was not a required text and its study was at the discretion of the teacher.) As the curriculum text acknowledged, ‘this view angers many Australian South Sea Islanders. They object both to the interpretation itself and to the fact that it has been made by non-Pacific-Islander historians.’[xxviii] What didn’t find its way into the curriculum was a more sophisticated and humane interpretation of oral history such as the one given by Ross Gibson, who says:

Cultures which do not rely on written records know their environment is their world of meaning, because landmarks hold the prompts to the stories that constitute knowledge. In such cultures only a fool would be careless with narrative, for to have no care about the stories of your setting is to nullify your life in the place that determines your survival.[xxix]

One of the strategies with which the ASSI have responded to this questioning of their testimonies is by trying to take control of the way they are represented into their own hands. The 2000 Protocols Guide: Drumming the Story: It’s Our Business! by the Mackay and Districts Australian South Sea Islander Association (MADASSIA) is a detailed response to these disappointments and the astute awareness of the politics of representation that resulted. The overarching statement of the Protocols is: ‘We value confidentiality and we are generally protective of our private information. Perhaps this is because we have felt that our information has not been handled well in the past.’[xxx]

Trans-generational trauma?

I would argue that a case can be made that ASSI suffer trans-generational trauma and re-traumatisation. Mrs Trieve’s story of her grandmother is testimony. In a documentary, Stori Blong Yu Mi, produced by Crossroad Arts, a Mackay arts organisation, Mrs Trieve speaks of the terrible scars from leg shackles around Katie’s small ankles, even after half a century. Perhaps these interpretations were felt, by ASSI as a re-traumatisation and, adding to this, perhaps they felt, they had in some unintentional way betrayed their ancestors by divulging their stories, if this way how academics responded.

How should those suffering trans-generational trauma and traumatic retelling be treated? Was an opportunity missed? What was the opportunity that was missed? Work done by theorists such as Shoshana Felman, Dori Laub and Cathy Caruth on testimony and trauma, can be applied here. According to Caruth it would be the opportunity to learn a new way of listening, ‘by carrying the impossibility of knowing out of the empirical event itself, trauma opens up and challenges us to a new kind of listening, the witnessing, precisely, of impossibility.’[xxxi] This act of listening requires something not only of the speaker but of the listener as well. Caruth speaks of a ‘new mode of seeing and listening … from the site of trauma that could create ‘a link between cultures’.[xxxii]

I argue that we need to learn to listen, to witness ASSI witnesses, in this ‘new mode’; we need to mobilise the tools of trauma theory and testimony. We need to formulate, and to ask, ‘enabling questions that would offer new directions for research’.[xxxiii] As Felman remarks, ‘What ultimately matters in all processes of witnessing … is not simply the information, the establishment of the facts, but the experience itself of living through testimony, of giving testimony.’[xxxiv] Such were the considerations and questionings that were directly pertinent to the creation of the commemorative pilgrimage tourist guide.

The making of ‘Uncle Cedric Andrew Andrew’s Mackay’

Impressed by the mourning and memorialising work evident in the Recognition Day bus tour I wondered if it were possible to make the political, cultural and social potency of the ASSI’s work available to the general public? I wondered if it was possible to somehow formalise a ‘new mode of listening and witnessing’ in a more material and permanent way?

Despite the many differences and disputes within the ASSI community I believe there is a general consensus on three agenda points. These are the desire for the general public to be aware of the history of the ASSI, and to appreciate and understand their identity and acknowledge the contribution their community has made to the economic and cultural wealth of the country in general and of the Queensland sugar industry in particular. I found myself asking: how could these predicaments be negotiated and how could these agendas be advanced? The answer I came up with was a tourist guide – a commemorative pilgrimage – with photographs, stories and meditations or prayers for a selection of these significant ASSI sites.

To advance this idea I wrote a proposal and, following MADASSIA’s Protocols Guide regarding protocols and permissions, emailed it to a number of local ASSI organisations and prominent individuals. I received only one response and letter of support from Mackay’s Australian South Sea Islander Arts and Cultural Development’s chairperson, Jeanette Morgan, with backing from the Elder Rowena Trieve. This was one major reason I chose to work with the Mackay community on this commemorative pilgrimage booklet; Mackay had chosen me. Another reason was that Mackay has the largest population of ASSI in Australia.

In October 2012 I flew to Mackay, picked up my campervan, which I’d left there and in which I lived, worked and travelled, and began the consultation, collaboration, writing, editing and photographing process for the booklet. My methodology incorporated trauma theory and the action research model in that ‘my intention was to actually change social conditions’[xxxv] and my hope was that the booklet would go some way towards achieve the three primary ASSI agendas discussed above. I had also investigated David Denborough’s narrative therapy practices and believed aspects of the methodology could be advantageous in working with the stakeholders and the ASSI community. The approach is based on the belief that the participants have experienced some form of trauma and, particularly, trans-generational trauma. When faced with the practicalities of the situation I found myself in in Mackay it wasn’t possible to employ this narrative therapy methodology for every site; nonetheless, it did inform my practice in a variety of ways and I used it as a template. As Denborough says, ‘Collective narrative documents can stand as a different form of historical testimony. Importantly, these are double-storied testimonies of history – testimonies of survival and trauma at once.’[xxxvi] This ‘double-storied’ concept is a way ASSI’s sensitivity to victim status, for example the ‘Kanaka’ terminology debate, could be dealt with. The double-story or subtext of a collection of significant site stories would reveal the traumatic aspects of the sites but also the maintenance, respect and care which transform them from traumascapes into sites of memory. Also, including meditations or prayers would conceptualise the sites as sites of pilgrimage rather than simply tourist destinations as well as acknowledging the importance of Christianity to the ASSI community as a way to healing and to reconcile with the violent histories of the past.

The choice of the ten sites was made in collaboration with Jeanette Morgan, as her organisation was to publish the booklet. In a series of meetings, I explained to the stakeholders that the booklet was aimed at tourists and the general population and that there was a word limit of about five hundred words for each story. I told them that I would take notes of our conversations, write up their story and present it back to them for feedback. I asked them, if, in the meantime, they could write a meditation or prayer for the site. Bob Hodda’s story about Rowellan Park and Ernie and Gertrude Mye’s story about growing up at The Palms are two examples that best illustrate the results of applying my methodologies.

Of Bob Hodda’s many stories the one we chose to use in the booklet seemed exemplary. It included his sensitivity to and respect for the sites, his decades long research, his relationship with the local ASSI and specifically with Uncle Cedric Andrew. The story focused on a visit made to the park by a group of ni-Vanuatu from the scouting movement who performed a traditional consecration ceremony over the graves.[xxxvii] This story demonstrated the deep spiritual and cultural importance of the sites. Another reason I wanted to include Bob and the park in the booklet was to give a poignant and powerful example of the relationship between ASSI and some members of the non-ASSI community. Bob wrote this meditation/prayer for the site.

Bob Hodda’s meditation-prayer for Rowallan Park

As custodians of the wealth of knowledge hidden within these boundaries and beyond, we treasure the memories of those who have passed on. We pray for the workers from Vanuatu who lie in these mass graves, proudly kept in the formation as found by us so many years ago, their history sought, their road works and camping grounds noted and well preserved. We also pray for Scouting legends Noel Weder and his sister Mona, who lie in a grave-site on the terrace, keeping watch! We hope and pray that all their spirits are at rest but still they have a presence in this land. We pray that these memories and the stones of remembrance for them all will remain forever in our minds and hearts – God Bless Rowallan Park – may it continue forever!

Ernie and Gertrude Mye’s story is the other most successful example of my chosen methodologies. The Myes invited me to their home and told many stories of the old days and life at The Palms. They spoke of the importance to them of the communal atmosphere, the lovely spring water, fruitful gardens, good fishing and food cooked over open fires, the bitterness of their removal from the river and the insights into the socio-economic reasons for the removal, the continued relationship with the site, the ongoing spirituality of connection with ancestors and beliefs and also of Uncle Cedric’s input.

Ernie and Gertrude Mye’s meditation-prayer for ‘All Along the Pioneer River’

As we sit around the crackling fore, telling the most interesting stories of those old days, we can hear the rippling tide coming in, the fish swirling and playing, curlews singing out on the banks of the river and the wind whistling through the trees. We thank God for what was beautiful and good and for that peace of mind. He is always with us. He is the key of everything today. Amen.

In both stories Uncle Cedric Andrew’s name and his Elder status were articulated. This was by design on my part, as the booklet was to be dedicated to him – Uncle Cedric Andrew Andrew’s Mackay: 10 significant sites for the Australian South Sea Islanders. There were a number of reasons for this. Primarily it was because I was in Mackay on 16 October 2012 when this much-respected Elder died. His knowledge informed much of the self-published book, Fields of Sorrow: an oral history of descendants of the South Sea Islanders (Kanakas)[xxxviii] (The title painfully ironic in the context of the ‘Field of Dreams’ sugar trail in the nearby township of Sarina.) We felt it would be appropriate to dedicate the booklet to him given his deep connection with the Mackay region and his passion to pass on his cultural and historical knowledge to the whole community.

The decision meant focusing on Uncle Cedric rather than working with individual stakeholders which had proved difficult logistically given both their, and my, time constraints and also, given their history of story sharing with academics, some understandable distrust. It also opened up a range of other sources: Uncle Cedric’s published work such as Fields of Sorrow and other documents he had contributed to held in the Heritage Room of the Mackay Regional Library, newspaper articles in which he was quoted and the reminiscences of those who had known and admired him. It also meant accessing private records such as the large plastic box containing Rowena Trieve archives.

It also meant one person I had to discuss the booklet with, and seek information from, was his daughter, Cristine Andrew. Cristine still lives in the family home her father built, and is determined to maintain his work and memory, work which they had done together. I visited her at home in Homebush and she generously offered to take me on a tour of the area in her car. During the drive story after story emerged. It was this tour that underpinned the stories and meditation-prayers for most of the remaining sites documented in the booklet.

Needless to say I wish the process of material gathering and writing had been more face-to-face with stakeholders rather than gained from secondary sources and a number of the meditation-prayers were, necessarily, quite generic. However, Jeanette Morgan, and Rowena Trieve read, edited and approved my draft copy with Rowena Trieve writing a statement of endorsement for the back cover.

The Mackay Regional Council designed and printed two hundred copies of the booklet, which were distributed to over fifty ASSI and non-ASSI locals one Sunday in July 2013 to accompany a bus tour of the sites. This was one of the events organised for the 150-year commemorations and the feedback from the participants was positive and emotive. The most common comment from non-ASSI Mackay residents, some in tears, was that they had had no idea these sites existed nor were they aware of their importance to the ASSI community. Perhaps, through the affect of their response, the participants would agree with Ross Gibson’s insights into landscape and country, insights which are ingrained in ASSI culture. Gibson says, ‘country is thus shaped by persistent obligations, memories and patterns of growth and re-growth. Governed by this system of physical and metaphysical interdependence, the country lives like something with a memory, a force of the past prevailing in the landscape still.[xxxix]

Conclusion

Perhaps if the conceptual tools of trauma, memory, place and narrative theory from the 1990s and 2000s had been available to the historians of the 1970s and 1980s, and they had been willing to employ them, a more sophisticated engagement with ASSI cultural and social sensitivities and aspirations might have resulted. Thus avoiding the disappointments of the hopes they held, after the renaissance of interest, for their emergence from being ‘the forgotten people’ and also avoiding, what I have argued was a re-traumatisation of the community. This is certainly an argument for a more hybrid approach in the social sciences which might have generated the political imagination necessary to dismiss the phantasmagoria, phantoms and imagos – the Golden-Syrup Man, the White-sugar Princess, the Boogeyman – to the murk of the colonial Fantasyland from which they emanate. I have listened, and heard, what the ‘Kanakas’ and the ASSI are whispering and I have realised that much can be learned from their obligation, memory, mourning, remembrance and survival work; much that could go towards creating Australia as a truly post-colonial society.

[i]Ross Gibson, Seven Versions of an Australian Badland (Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 2002), 2

[ii] Ibid

[iii] Patricia Mercer, White Australia Defied: Pacific Islander Settlement in North Queensland (Townsville: James Cook University, 1995), 1

[iv] Clive Moore, ‘The Pacific Islanders’ Fund and the Misappropriation of the Wages of Deceased Pacific Islanders by the Queensland Government’, Public Lecture, School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics, University of Queensland, 15 August 2013, 6.

[v] Mercer, 41–2.

[vi] Clive Moore, Kanaka: A History of Melanesian Mackay (Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies: Boroko and the University of Papua New Guinea Press, 1985), 139.

[vii] ‘Contract for Polynesian Labour 1868’ in C.M.H. Clark, ed., Selected Documents in Australian History 1851–1900 (Melbourne: Angus and Robertson, 1955), 210

[viii] For details of rations see ibid., 210.

[ix] Tracey Banivanua-Mar, Violence and Colonial Dialogue: The Australian-Pacific Indentured Labour Trade (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2007), 134, see note 52.

[x] Pacific Island Labour Act.

[xi] Moore, Kanaka, 284.

[xii] Moore, ‘The Pacific Islanders’ Fund’, 11

[xiii] recognition documents what they said ????

[xiv] Maria Tumarkin, Traumascapes: The Power and Fate of Places Marked by Tragedy (Melbourne: University of Melbourne Press, 2003), 12

[xv] Noel Fatnowna, Fragments of a Lost Heritage, ed. Roger Keesing (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1989), 27.

[xvi] ‘Everyday Brave’, episode 1, For Who I Am: Bonita Mabo, Marcom Projects, 2002.

[xvii] Gibson.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Kay Saunders, Workers in Bondage: The Origins and Bases of Unfree Labour in Queensland 1824–1916 (Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1982), 119.

[xx] Mrs Rowena Trieve, ‘Letter to the editor’, Daily Mercury, 16 July, 1998.

[xxi] Sigmund Freud, ‘Mourning and Melancholia’ in The Penguin Freud Library: new introductory lectures in Psychoanalysis, Vol. 2, (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1971), 254.

[xxii] Gibson, 166.

[xxiii] Marilyn Lake, Faith: Faith Bandler, Gentle Activist (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 2002), 207

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Anna A. Cheng, The Melancholy of Race (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 3, ii.

[xxvi] Patricia Mercer, ‘The Forgotten People’, a review in Journal of Pacific History 15, no. 2 (1980): 126. Quoted in Sharon Bennett, Clive Moore and Max Quanchi, eds, Australian South Sea Islanders: A Curriculum Resource for Secondary Schools (Brisbane: Australian Agency for International Development, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Queensland Department of Education, 1997), 41.

[xxvii] Bob Reece, ‘The Forgotten People’, a review in Oral History Association of Australia Journal 1 (1978–79): 116. Quoted in Bennett, Moore and Quanchi, 41.

[xxviii] Bennett, Moore and Quanchi, 41.

[xxix] Gibson.

[xxx] S. Waite, Mackay and District Australian South Sea Islander Association: Protocols Guide: Drumming the Story: It’s Our Business! (Mackay: Mackay and District Australian South Sea Islander Association, 2000), 13.

[xxxi] Cathy Caruth, ed., Trauma: Explorations in Memory (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 9.

[xxxii] Ibid., 9

[xxxiii] Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History (New York and London: Routledge, 1992), xvi.

[xxxiv] Ibid., 85.

[xxxv] Margaret Sargent, Sociology for Australians (Melbourne: Longman Cheshire, 1983), 65.

[xxxvi] David Denborough, Collective Narrative Practice: Responding to Individuals, Groups and Communities who have Experienced Trauma (Adelaide: Dulwich Centre Publications, 2008), 42.

[xxxvii] Ni-Vanuatu refers to all Melanesian ethnicities originating in Vanuatu as well as to nationals and citizens of Vanuatu

[xxxviii] Cedric Andrew, Fields of Sorrow: An Oral History of Descendants of the South Sea Islanders (Kanakas), eds Cristine Andrew and Penny Cook (Mackay: self-published, 2000)

[xxxix] Gibson, 63.

© Kathleen Mary Fallon