Live Encounters Magazine May 2021

Dr Caroline Higgins is Professor Emeritus of History and Peace Studies at Earlham College. She earned a Ph.D in History and Humanities from Stanford University in 1970 and subsequently focused her work on Latin America, Women’s Studies, and Peace theory and practice. Her writings include a novel, Sweet Country, (1979), about the Chilean coup d’etat of 1973. The book was named one of the best of the year by The New York Times in 1979. She led numerous off-campus study programs to Latin America. Upon retirement from Earlham College, she moved to Chile with her husband, the philosopher Howard Richards, where they devote themselves to small-scale organic agriculture and community development. Their organization, Chileufu, can be accessed online at chileufu.cl.

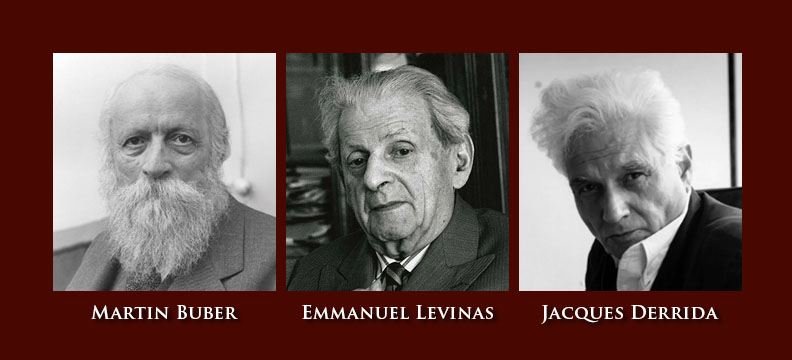

Encounter: Martin Buber, Emmanuel Levinas, Jacques Derrida

And the Question of Otherness

1

Socrates

“Tell me, Socrates, can virtue be taught?” So begins one of the most highly esteemed works on values and education ever written, although Socrates fails to answer the question posed or any other question. No matter: by the end of the dialogue (1) the reader is apt to see Socrates’ relentless if inconclusive arguments as incomparably richer than the muddled assertions made by persons unpracticed in critical reasoning. But if Socrates was deemed an extraordinary thinker in 380 B.C., the resumed dramatic date of the dialogue, the public had reversed itself by 399 B. C., when the peripatetic philosopher was condemned to death for atheism and unwholesome influence on youth.

Is there a lesson to be learned here? The generations which followed Socrates, for their part, have lionized Socrates and ridiculed the ignorant Athenian democracy which condemned him, although a few, like the American journalist I. F. Stone, have defended the Athenians for surmising that Socrates, with his deceptively modest manner but elite viewpoint, in fact aimed at subverting the city’s democratic values, institutions, and folkways (2) Forbearing to decide one way or another, we are left with perplexing questions: When is subversion justifiable? Which values are worth preserving? Where do values originate? Who gets to decide? To what extent does philosophy continue true to foundational principles, or alternatively, how far does it move to reinvent itself in light of the new demands made on it? Has philosophy been discredited? Where do we stand in regard to values today?

2

Martin Buber, Emmanuel Levinas, and Jacques Derrida

Among the twentieth century philosophers critiquing Western philosophy after the defeat of fascism, three were especially remorseless. They dethroned rationality from its privileged place in the liberal arts, advancing an alternative position as to human being and the origin of ¨morality,” what Socrates would call ¨virtues¨and others ¨values.¨

Martin Buber (1876-1965) in his seminal book, I and Thou, (3) identified a precognitive and as it were primordial encounter between two humans which elicits the original and essential response: Do not kill the other. Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995), following Buber, also privileged the relationship between self and other (l´autre). Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), radicalized the concept of the Other ((tout autre), in his later years sometimes anchoring his comments in analyses of stories from Hebrew Scriptures.

While there are important similarities among these writers—indeed, their shared understandings form the subject of this essay—it is important to note that they did not form a school. Buber denied he was a philosopher, asserting that his reflections were centered on the personal. Derrida described himself (perhaps disingenuously) as an historian. Unlike Buber and Levinas, he declared himself an atheist. Levinas thought it important to prove himself as a professional philosopher (rather than, like Buber, a Jewish thinker), and his arguments clearly follow the paths of reasoning we associate with philosophical thinking.

Although they did not form a school they read the same books and as young men studied with the same masters, including Husserl and Heidegger. As children of observant Jews they understood the pull of ancient ideals as well as the persuasiveness of modernity and progressive discourse.

Once Derrida had settled in Paris to pursue a degree n philosophy, he became friends with Levinas. It is unlikely that Derrida knew Buber personally, and he never acknowledged that Buber had influenced him. Yet Buber influenced Levinas who in turn influenced Derrida. (4)

One of the ways that we can approach these thinkers, whose lives collectively spanned the twentieth century and more, is to note their discursive intersections, where their works both converge and depart from a similarly situated ontological and ethical problematic.

3

1942

Consider the three in 1942:

Martin Buber is now a professor at the Hebrew University in Palestine. He had fled Germany in l938, after Hitler´s rise to power, when Buber was dismissed from his post teaching philosophy the University of Mannheim. At the Hebrew University he teaches introductory courses in philosophical anthropology and philosophy, and in sociology. Although he had completed I and Thou in the late 1920´s, a German edition published in the l930´s received little attention. He will become well known when the book appears in English after the war.

Emmanuel Levinas is a prisoner of war in Hanover, Germany. He had served as a Russian/French translator in the French army before being captured in l940. His status as a war prisoner saved him from the Jewish camps, although he was almost murdered when released in 1944.

Jacques Derrida is a twelve year old schoolboy living in his native Algeria. On the first day of class he is expelled from the French lycee by order from the Vichy government: Vichy is enforcing the anti-Semitic quotas which drasticaly limit Jewish children´s access to schooling. The child refuses to attend the Jewish lycee set up by the expelled teachers and students, spending his time reading Gide and Rousseau and Sartre while he daydreams of becoming a professional football player.

Later Derrida was to observe that he was twice marginalized, first as a Jew, then as an Algerian. Since French intellectual life is centered in Paris– and no one expected Algerian Jews to end up there studying and then teaching at l’Ecole Normale–he was always the Other, His works must be read in light of his sense of alienation.

It is futile to ask to what extent their war experiences shaped the subsequent views of the three philosophers. They themselves probably couldn´t say. What is clear is that privileging ethics over ontology , and deriving values from the Encounter with the Other spoke to the convictions of thousands of people who faulted Western philosophy and more generally Western Civilization for dehumanizing those who could not or would not be assimilated into the hegemonic culture. While three European philosophers can hardly take all the credit for a now almost universal revolt against exclusion and hierarchy—against the privileging of White, European rationality over local narratives and practices—they did open up new discursive spaces big enough to include all who wanted to inscribe their own stories and claim their own identities.

4

Encounter: I and Thou

Buber completed his best known work, Ich und Du, in 1923. It was translated into English as I and Thou, a title which subtly conveyed the book´s tenor: Since Thou is archaic, used only in prayers and poetry from former times, we are appraised of Buber´s spiritual orientation. In the body of the text, however, “you” replaces “thou.” It is not only or even predominantly a religious book. It crosses boundaries between philosophy, theology, psychology, and social commentary. It is both prose and poetry. Although the book advances an argument, it seems like a book written under the influence of exalted and prophetic passion. Indeed Buber admitted as much when, as an old man, he wrote, “At that time I wrote what I wrote under the spell of an irresistible enthusiasm. And the inspirations of such enthusiasm one my not change any more, not even for the sake of exactness.” (5)

For all of these reasons the book achieved an enormous success, especially among students of the humanities. Buber became a world-renowned figure, nominated the Nobel Prize, among other honors. His status as a philosopher is more ambiguous– he continued to write on literary and humanistic subjects and on Zionism (the idealism of which he shared even as he criticized it)—but he was indifferent to disciplinary norms and expectations. Similarly, although I and Thou betrays its author´s Jewish orientation, it is not about Judaism or addressed to Jews over others.

Buber claims that “man´s” world is two-fold: There is the I-You relationship and the I-It. Each of these pairings establishes a mode of existence, but the I-You can be spoken with one´s whole being, whereas “ I-It can never be spoken with one´s whole being¨(p 54) While the I-You establishes a world of relation, I-It does not. “It” does not participate in experience. Rather, it allows itself to be experienced, but is itself not concerned. “It” constructs nothing and nothing happens to it.” (p 56)

Humans can relate not only to each other but also to nature, to spiritual beings and to “the Eternal You:”

In every sphere, through everything that becomes present to us, we gaze toward the train of the eternal You: in each we perceive a breadth of it; in every You we address the eternal You, in every sphere, according to its manner (p 57)

While the “eternal You” seems to be the Godhead, it is notable that Buber claims he knows nothing of God but only of the relations people have with God. He writes:

…whoever says “God” and really means You, addresses, no matter what his delusion, the true You of his life that cannot be restricted by any other and to whom he stands in a relationship that includes all others. But whoever abhors the name and fancies that he is godless—when he addresses with his whole devoted being the You of his life that cannot be restricted by any other, he addresses God.( p 57 )

According to Buber, there is an intimate relation among what he terms “presentless, Encounter, and relation. When “You” becomes present, presence comes into being. Without “You,” “I” has only the past. What is essential is lived in the present (p 64). The You, however, encounters the I “by grace.” It cannot be willed, for the objects willed lie outside relatedness. “The You encounters me,” he writes. “But I enter into a direct relationship to it.” Indeed, Buber indicates that in order to be, I require a You. “In becoming I, “I say You.” (p 62)

And what of the It? Unfortunately, every You is by nature doomed to become It or at least to “enter into thinghood” again and again. The You must become an It when the relation between I and I/you has run its course. (p 84) Men can become accustomed to the I/It world in a utilitarian way, regarding the world as something to be used and experienced. Men can divide their lives into two defined districts: institutions and feelings—the It district and the I district. (p 91) “But the severed It of institutions is submerged in the It World of the economy and the state, both of which see You as “centers of services and aspirations that have to be employed according to their specific capacities. (p76)

Buber´s utter originality is apt to raise questions today as it did when I and Thou was published. Is the book a contribution to philosophy? Is it sui generis? Perhaps it might be better considered as an extended personal reflection, the fruit of his vast reading, his religious formation, and his tumultuous history. Whichever original philosophical contributions he made tended to be obscured by his rather repetitive prophetic locutions. Yet Buber without apology named relationships, not rationality, as that which constitutes human being. Epistemology and ontology, long the sin qua non of Western philosophy, give way to ethics as the ground of human being. The Encounter with the Other, both psychologically and historically, is pre-cognitive. It is essential to the formation of identity. It makes demands of us, at the least openness to the possibility of You, and authenticity in giving oneself over to the I/You relationship.

Many, including Emannuel Levinas, found much to admire in Buber . At the same time, Levinas expressed some reservations. Buber´s ethics insist on establishing and maintaining I/You relationships, but nothing beyond that seems to be required. It is as if ethics has now completed its function. The language of I/You doesn´t appear, at least according to this reading, to generate its own ethical grammar. But Buber, very widely read in the postwar period, invited people to reconsider their assumptions about virtue, knowledge, and the relation between the two. He mapped out an ethical terrain available not only to those open to religious claims but also to skeptics who appreciated the porous borders between religion, philosophy, and humanistic learning which Buber adumbrated.

5

L’autre

In a commentary on a brief work by Martin Buber , Emmanuel Levinas affirmed that the thought of war was always with him. His preoccupation is manifest in his great work, Totality and Infinity. The preface begins with a reference to Heraclitis who famously claimed that “War is the father of all;” Levinas discusses this paternity in philosophical terms. What war reveals is “fixed” in the concept of totality, which, he claims, dominates Western philosophy. In a totalizing system “the meaning” of individuals derives from the totality. The present is incessantly sacrificed to a future which is constantly referred to “in order to bring forth its objective meaning.” (6) Our common conception of peace as established by force of war is mistaken., but it follows from the totalitarian impulse. A moralilty which claims to aim at peace while at the same time making it impossible is hypocritical.

What is essential to peace is a rupture with the underpinnings of Western morality. What must be introduced is an eschatology of messianic peace to superimpose itself over the ontology of war. But where does such an opposition come from? Neither from the regime of evidence, nor from a teleological system. Indeed, what we are looking for is

a relationship with a surplus always exterior to the totality, as though objective totality did not fill out the true measure of being, as though another concept, the concept of infinity, were needed to express this transcendence with regard to totality, non-incompassable within a totality and as primordial as totality. (23)

Now we are in a position to understand the title of the work: “Totality” must by opposed by “infinity” which is beyond history and sacrifices for the future. In infinity, beings exist in relationship, but not on the basis of totality. The relationship with wars and empires is broken. The hypocrisy of our world, attached as it is to “both the philosophers and the prophets” (i. e., both Greek and Hebrew) lies exposed. (24)

How to begin? With the Other. With what is exterior. Or more precisely, with “the infinity which is produced in the relationship of the same with the other” (26) Infinity does not first exist, then reveal itself. Rather, infinity is produced and revealed in me when welcoming the Other.

At this point it is clear that like Buber, Levinas challenges the traditional Western assumption that morality precedes from knowing. Welcoming the Other—the ancient Biblical and also Homeric injunction—and the total giving of oneself is precognitive and also the condition for consciousness and activity. But whereas for Buber the Encounter appears to satisfy the requirement of ethics, which has now replaced ontology as ¨first philosophy,” for Levinas the Encounter engenders an infinite debt to the Other mandating welcoming, hospitality, and the total giving of oneself.(298)

It is the face of the Other which one acknowledges before using reason to arrive at conclusions. The “face of the Other” remains infinitely foreign, but it also gives of itself in language. This is in contrast to the ontological assertion that the Other is an object about whom we make judgments, treating him/her as a finite being in a totalitarian system.

In his later works Levinas connects his philosophy to twentieth century history, arguing that the West´s embrace of instrumental reason, with its value-free orientation, displays a “will to domination.” It is implicated in the rise of European totalitarianism and the great twentieth century wars.

As in the case with Buber, Levinas´contributions to philosophical thought are inflected in Biblical tropes. It is sometimes said that Levinas attempted to “translate Hebrew into Greek, “ i. e., to reconfigure Western philosophy by bringing to it a biblical perspective. It is interesting to note that for a decade and more he delivered a Sabboth message every week at the Ecole Normale Israelite Orientale (ENIO), a school for Jewish students in Paris which he directed.

6

Tout autre est tout autre

Finally we arrive at Jacques Derrida, the enfant terrible of our philosophical trio, the one who aroused both wide admiration in learned circles but also enormous anger and resentment. He was named one of the three greatest philsophers of the twentieth century by the New York Times, the others being Wittgenstein and Heidegger. (7) Yet, in 1992, when Cambridge University proposed to give him an honorary degree, a group of well –known thinkers, including John Searle, wrote a letter of protest, attacking Derrida for his putatively specious arguments and impenetrable prose. (8)

Derrida had left his native Algeria in 1949, passing his entrance exams to the l’Ecole Normale on his second try. Once his M. A. was awarded, he became a member of the faculty, remaining there until 1983, when he assumed a position at l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes where he remained until the end of his life. He also taught courses at other universities including Yale and the University of California at Irvine.

His stature as a world thinker was assured in 1967 when he published three books (9) which defined his vocation as a major critic of Western philosophy and civilization, irritating many by his criticisms of ideas and institutions which people generally admire, or, at least, accept without question. Nothing escaped his critical gaze, neither God nor country nor individualism nor conformity, neither law and order nor claims to authenticity and purity. Perhaps his two most infamous qualities were his writing style, which, although it could be described as highly original and brilliant, few could penetrate without great effort; and his innovative methods of arguing against “truth” and “meaning:” there are no fixed meanings, but rather free-floating signifiers whose intelligibility is constantly deferred to other terms which themselves depend on yet other terms.

He followed Heidegger in critiquing the dominant Western philosophical conviction that words refer to things outside the realm of language itself: Derrida labeled the realm beyond words, which language supposedly referenced, “presence.” Presence is wrongly taken as an abiding guarantor of truth. We attempt to found a necessary relationship between our words and an always already existing non-verbal reality. The metaphysics of presence, moreover, constructs a set of binaries beginning with presence/absence itself and including the ones that circulate widely today even in popular discourse: rationality/irrationality, man/woman, culture/nature, soul/body, white/black, law/chaos, heaven/hell, sameness/difference, power/impotence. Obviously in such binaries one term is favored over another. As our thoughts are structured around them, so are our institutions and practices. Derrida refered to such thinking as logocentrism: as we can deduce from the binaries, logocentrism is phallocratic, patriarchal, and militaristic.

Derrida attempts to reveal “presence” hidden in the discursive strategies of important texts, developing a particular way of reading called “deconstruction,” Ultimately he aims to show that language usage is unstable and incredibly complex. In his readings texts reveal sub-texts which disrupt the purported intended meaning or structural unity. Yet he does not expect to unmask once and for all the presence, the logocentrism which constitute our erroneous interpretive logic. Against such a universal enterprise he proffers careful readings of particular texts.

============

Critics commonly identify two phases in Derrida’s professional life, the first centered on ontology and its deconstruction, and the second on ethics. As he himself has observed, however, ethics are imbedded in the earlier works as well as in the latter. Indeed, discerning reads have been quick to see the originality of the philosopher´s ethical challenges implicit in a critique of logocentrism.

Still, latter works like Specter of Marx (10), which argues for a prophetic messianism awaiting a democracy to come, and The Gift of Death (11) are overtly

dedicated to interrogating particular texts as to their ethical implications. In that effort he influence of Levinas is everywhere apparent. As he admitted in an interview in 1986, “Faced with a thinking like that of Levinas, I never have an objection. I am ready to subscribe to everything he says.” (12)

The Gift of Death is particularly interesting for its focus on “the other” in light of Hebrew Scripture. The Levinasian insistence of welcome and hospitality as grounding ethical practive is assumed, but the addressee—the “other” is reconsidered. “Tout est tout autre” can be taken as a tautology: It can mean “Every (one) is an other “, or, if the second “tout” is an adjective, the term would mean “every (one) is a bit, or totally or somewhat “other.” If we say “totally Other, then we are defining God. Of course, this linguistic ambiguity can be discerned in Levinas´work. The other, always beyond our understanding, is an instance of Otherness.

That ethics must rest on a precognitive recognition of the obligation the other presents to us as he confronts us face to face, rather than on our human reasoning, is the anchor of Levinas´ethics, to which Derrida says he subscribes. However, in The Gift of Death Derrida draws our attention to the difficulty of inscribing our choices in an ethical system when God is “tout Outre” and therefore unknowable: (“I am who I am, “ God says to Abraham, as if to say, “Stop asking: That is all you will get from me”). And yet He commands absolute obedience. Then there is the other difficulty: “ Levinas is unable to distinguish between the infinite alterity of God and that of every human. His ethics is already a religion. In both cases the border between the ethical and the religious becomes more than problematic, as do all discourses referring to it.” Indeed, the concept of responsibility now lacks coherence. It continues to function, as does justice, international law, etc., but these discourses “hover around a concept that is nowhere to be found” “And here Derrida permits himself a small moment of pique: Rather than admitting the aporias that beg to be acknowledged openly, people blame as nihilistic or relativist the honest deconstructionist “ and “ all those who remain concerned in the face of such a display of good conscience.” (p. 84)

Derrida illustrates with a commentary on the narrowly averted sacrifice of Isaac:

The sacrifice of Isaac is an abomination in the eyes of all, and it should continue to be seen for what it is—atrocious, criminal, unforgivable, Kierkegaard insists on that. The ethical point of view must remain valid: Abraham is a murderer. However, is not the spectacle of this murder, which seems untenable in the dense and rhythmic briefness of its theatrical moment, at the same time the most common event in the world? Is it not inscribed in the structure of our existence to the extent of no longer even constituting an event? It will be said that it would be most improbable that the sacrifice of Isaac would be repeated in our day, and it certainly seems that way. We can hardly imagine a father taking his son to be sacrificed on top of the hill on Montmartre. If God did not send a lamb as a substitute or an angel to hold back his arm, there would still be an upright prosecutor, preferably an expert in Middle Eastern violence, to accuse him of infanticide or first-degree murder, and if a psychiatrist …were to declare that the father was “responsible,” carrying on as if psychoanalysis had done nothing to upset the order of discourse on intention, conscience, good will, etc., the criminal father would have no chance of getting away with it. He might claim that the wholly other had commanded him to do it, and perhaps in secret (how would he know that?) in order to test his faith, but it would make no difference. Everything is organized to insure that this man would be condemned by a civilized society. (But) the same civilized society… “puts to death…or allows to die of hunger and disease tens of millions of children (those relatives or fellow humans that ethics or discourse of the rights of man refer to) without any moral or legal tribunal ever being considered competent to judge such a sacrifice, the sacrifice of the other to avoid being sacrificed oneself… (pp 85-86)

Derrida has more to say about the sacrifice of Isaac, and more generally the challenge of rescuing the concept of human responsibility from a biblical discourse which privileges obedience to God who is Other to us even as our neighbor is other. In a provocative and close reading of several passages from Matthew, he attempts to link Otherness to the themes of salvation, gift, and, perhaps most provocatively, secrecy. In reaching for a conclusion to the discussion he points to a way to reconceptualize God in a manner which accounts for human responsibility and autonomy as well as otherness:

We should stop thinking of God as someone over there, way up there, , and what is more –into the bargain, precisely, more than any satellite orbiting in space, capable of seeing into the most secret of the most interior places. It is perhaps necessary, if we are to follow the traditional Judeo-Christian-Islamic injunction, but also at the risk of turning it against that tradition, to think of God, and the name of God, without such a representation or such idolatrous stereotyping. Then we might say: God is the name of the possibility I have a keeping a secret that is visible from the interior but not from the exterior. As soon as such a structure of conscience exists…there is what I call God (there is ) what I call God in me, he is the absolute “me” or “self,” he is that structure of invisible interiority that is called, in Kierkegaard´s sense, subjectivity. And he is made manifest, he manifests his non-manifestation when, in the structures of the living or the existent, in the course of phylo- and ontogenetic history, there appears the possibility of secrecy…that is to say, when there appears the desire and power to render absolutely invisible and to constitute within oneself a witness of that invisibility. That is the history of God, of the name of God or the history of secrecy, at the same time secret and without any secrets. (p 108)

© Dr Caroline Higgins