Live Encounters Magazine Volume One December 2020

Dr. Cauvery Ganapathy is a Strategic Affairs Analyst and currently works as a Strategic Risk Management Consultant. She has been a Research Associate with the Office of Net Assessment under the US Department of Defense previously. As a Fellow of Global India Foundation, she has presented and published at various national and international forums. She has been a recipient of the Pavate Fellowship to the University of Cambridge as Visiting Research Faculty and a recipient of the Fulbright-Nehru Doctoral Fellowship to the University of California, Berkeley. Cauvery interned with the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore, on the Nuclear Industry in India.

Abstract

Most issues in international relations acquire multiple identities. Oftentimes, the only purpose this serves is to compound a singular or simpler issue to begin with. The narrative of the Tibetan issue is an instance of such entanglement. The Tibetan issue, to a large part of the world, much of India included, resonates at the level of an ethno-cultural and religious suppression which is fast devolving into a humanitarian crisis. However, to consider Tibet through that prism alone- as it is most commonly done- is to overlook its significant strategic relevance, and to be willfully in denial of what, this commentary argues, is at the heart of the unquiet peace along the Sino-Indian border. The purpose of this commentary is two-fold- One, to upraise the strategic relevance of Tibet and argue that it may perhaps be time for it to feature more prominently in New Delhi’s strategic outreaches, and two, to upraise a hope that the struggles of a people long suppressed not be made a casualty of great power politics.

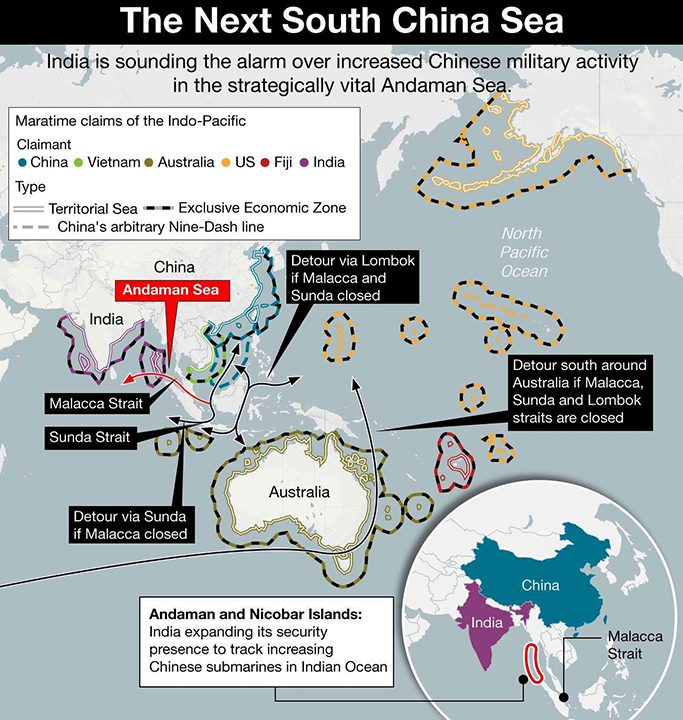

In a strategic arena intrinsically tied to considerations of Chinese behavior and approach, there appear two areas that New Delhi could increase its focus on in the near future. While the Andaman Islands with its vital positioning at the mouth of the Malacca Straits qualifies as one, the Tibetan plateau may well emerge as the second. It is a configuration that would irk Beijing endlessly and not one that would, should or could be made blithely in any measure either. The fact of a contiguous land border that India shares with China and the remarkable growth in the PLAN’s capabilities and their increased presence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), present the opening of fronts that India must confront more actively and imaginatively. These two territories, then, offer a most cogent markings of a strategic theatre that India needs to cultivate.

The central intent of this commentary is to focus on the second option – Tibet.

While Tibet forms the main focus of this commentary, a brief note on the Andamans is called for, given the reference made to it. The Andamans is a strategic asset that New Delhi appears poised to finally exploit most potently in its approach towards Chinese presence in the IOR. The landing of a US Poseidon P-8 on the island in late September, 2020 should be taken to be indicative of a much more open stance on the part of India to accept and utilize the strategic value of the Andaman Islands at a time when the Chinese presence in the IOR appears to be increasing. The Andamans, in many ways, acts as a gateway to the Malacca Straits, indisputably the most critical chokepoint where global energy trade is concerned. This development must be contextualised also in the backdrop of the conclusion of a series of military logistics agreements that India and the US have recently signed, beginning with the LEMOA and the COMCASA and concluding with the BECA and MISTA earlier this week. The fundamentals of all of these agreements rests on enhancing the scope of interoperability between American and Indian naval forces. Attendant to any such intent must necessarily be a robust positioning in the IOR, and the Andamans offers an unparalleled location to base such a collaboration out of.

On Tibet

Tibet and the Tibetan cause have resonated internationally over the past seven decades. The central point of interest relates, quite understandably, to ideas that emanate from the realm of humanitarian considerations. The struggles of the Tibetan people, living in exile in large part, have come to acquire the status of a great humanitarian tragedy being played out since the last century and is one that appears to have caught the public imagination like no other. Yet, support and advocacy for it remains conditional upon the troughs of political relations with and within other countries.

The Tibetan issue represents an anomaly in that, what is also a critically important strategic issue is being dealt with by most nations, as a humanitarian one. To an objective observer, a humanitarian issue must take precedence in any case, it would appear. However, international relations and global politics has been a testimony to the fact that when it comes to decision-making, it is most often the strategic issues that enthuse an expedient and invested response from governments. The tragedy of the Tibetans has been that their cause is largely universally considered a humanitarian one and consequently gets featured much lower on the list of priorities by nations other than China, while significantly, the Chinese themselves see the Tibetan issue as one of strategic importance and national security. It is in this backdrop that the importance that Beijing accords to the cause of controlling Tibet and its diffidence to any apparent international condemnation must be understood, while attempting to locate the apparent ambivalence of other countries to the issue.

This commentary urges a ‘reconsideration of Tibet’ along parameters of relevance other than the humanitarian one. One could take pains to underline yet again that an issue should be most critical by virtue of it being a humanitarian one alone, but it would seem like harping on a truism which would serve no purpose. Instead, if the raising of an issue to the level of strategic – and other- considerations is what would accord it the immediate and unqualified credence and support it deserves, then that is what must be done. A change in the narrative is required for Tibet. While the Dalai Lama is and will perhaps remain the most recognizable symbol of non-violent protest, there comes a time to reckon whether an approach needs to be supplemented. The bold strides that the elected Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) has recently been making is perhaps just such an option. Similarly noteworthy are the multiple steps that the US Congress and the most unlikely of administrations in US history, has taken to be openly supportive of the Tibetan cause and raise the prospect of retributions.

A similar change in narrative on the Tibetan question may perhaps be useful within India too. India’s position on Tibet, for one, could well be classified as one of calibrated empathy. There are the undoubted acts of statesman like courage – or, strategic foresight, as many with the benefit of hindsight over India’s Tibet policy would perhaps argue – that allowed for a fleeing people to be provided a home within Indian territory. Yet, instances of allowing their struggle to become a victim of the changing moods of the country’s domestic political disposition as also the vagaries of international relations abound equally, and more.

India would need to upgrade the strategic importance it openly attaches to Tibet for a change of such a narrative to take place. To begin with, underlining Beijing’s view of Tibet and the undeniable strategic value it places on the territory should find a mirror in India. Tibet’s critical relevance to Beijing emanates from a twin concern —

The first, that it is the periphery that could make the Chinese core susceptible. The Chinese predicate it on their traditional strategic understanding of ‘neiluanwaihuan’ which believes that any chinks in the domestic armour makes one susceptible to foreign aggression;

Second, that it is the literal fountainhead from which Chinese water security and territorial hold of the downstream countries of South and South East Asia emerges. The weaponization of water that the Chinese could implement with a total control of Tibet, would be as effective as any resource war that the world has seen so far.

In the intertwining of these two identities that Beijing has ascribed to Tibet, lies the misfortune of a people that are finding themselves in the crosshairs of what is essentially a strategic and tactical calculation that is deeply invested in wiping their very identity out.

Dulong Jiang/ Irrawady, Bhote Kosi. Arun, Karnali, Trishuli.

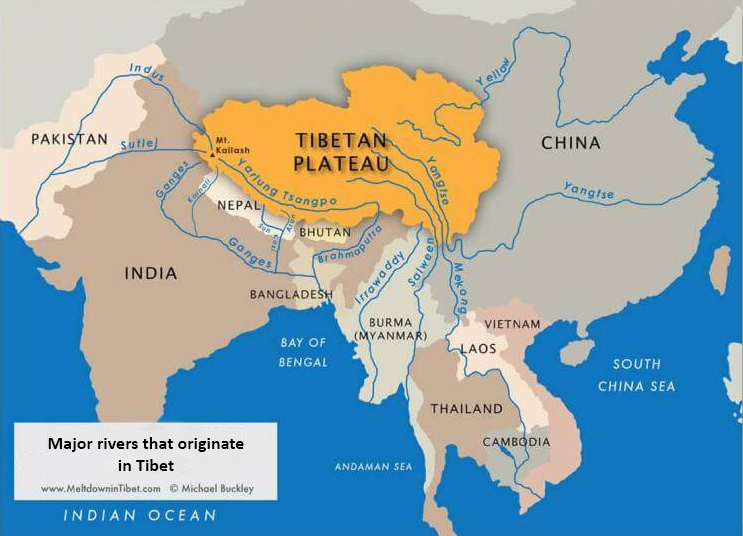

To China, the significance of Tibet may be identified as both strategic and tactical. Strategic because, in addition to its position as frontier land, there are ten river systems which originate in the Tibetan plateau and the control of which is a crucial area of interest. Controlling Tibet, then, translates into gaining control over the destinies of all the downstream countries that depend on access to these rivers for their sustenance. Water security is a natural, non-negotiable concern for every country- as a result, it is also a threat multiplier. Since the times of Mao, Tibet’s promise of freshwater and the agrarian bounties of its fertile soil have made it absolutely essential for the Chinese state to have complete and unfettered access to Tibet and its resources. These resources now also include the mining of critical minerals.

Second, tactical because, of the identification of Tibet as ‘the palm that holds the five Himalayan fingers’ of Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Ladakh, Nepal and Bhutan, together- an idea that finds extensive exposition in Mao’s thoughts. This positioning of Tibet makes it absolutely imperative for the Chinese to maintain a hold over it if they wish to enjoy any tactical advantage of higher ground entry into the five territories. In this context, it may be underlined that what transpired in Ladakh earlier this year should not perplex anyone that has followed the patterns of Chinese actions where any perceived Indian focus (whether through the building of infrastructure, or movement, or legislation) on any one of these five ‘irritant points’ calls for an immediate redressal through return to status quo, often at the cost of precipitating a conflict.

One telling indicator that this is the Tibet that the Chinese see, are the heads under which a visible Chinese policy towards Tibet may be classified and compared with to their traditional policies elsewhere. Chinese political history appears to favour the pillars of defense, development, migration and homogenization through ethnic classification in peripheral areas, that it considers as principle national security risks. The CCP’s approach to Tibet demonstrates these four features in ample measure. Building on these and consolidating them are the instruments of surveillance and subjugation. This consolidation of the periphery is implemented through an easily discernible pattern —

First, through propaganda to create a milieu that would make the need to ‘protect’ the territory a given; Second, to undermine the social and cultural elites; Third, to arrange for migration of the majority population into the territory; and, fourth, to make this newly migrated population stakeholders by integrating them into a model of economic growth that is irrevocably tied to the aegis of the core-in this case, the CCP in Beijing.

This is, in fact, a pattern that marks every overreach of the Chinese state along regions which could qualify as its periphery- it begins with Tibet and stretches through Xinjiang, Taiwan, Inner Mongolia and finally, Hong Kong.

Building on these precepts are the two flagship projects in Tibet- the Qinghai Tibet Railway and the South-North Water Diversion Project, both unique enablers of the Chinese state’s apparent defense and strategic objectives. A continuing reticence on part of actors such as India to build on the momentum the US has been building, in expressing and demonstrating their support for the Tibetan cause would lead to an easy implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative, which in turn would further the entrenchment and control of access to Tibet that these two projects already accord Beijing. Furthermore, another problem with the BRI succeeding in a place like Tibet is that it would then increase the stakeholders in the oppression of the Tibetans- a virtual death-knell for their struggle for freedom.

Now, there is no reason to believe that New Delhi thinks of Tibet in ‘non-strategic’ terms. However, it is necessary at times to reflect a view through action, when an implicit understanding alone does not suffice. Doing so would send effective signals to Beijing about the stake and importance that India accords the Tibetan issue. Simultaneously, it would also remove the garb around the considerations that must necessarily be offered to the other cause- that of Tibetan identity -which has ended up a casualty of larger strategic imperatives. There was a refreshing change noted with the presence of a senior minister from the BJP at the funeral of the fallen Tibetan soldier recently. However, this act of open recognition and support was immediately undercut by the deleting of the Minister’s tweet referring to his attendance and homage. There is an inherent value in a nation being identified with the normative choices it stays true to. To not openly recognize and stand by the struggles of a people that have now even come to serve in our defense forces should, then, generate a moral compunction that leads to reckoning.

The creation of silos could sometimes offer creative solutions. To identify the Tibetan cause as a strategic one that must be fought accordingly and assurances accordingly offered, would be to create a space where the simultaneous and related suppression of the Tibetan way of life could then be separated from the equation and whereby the support offered to the Tibetan activists would not be rendered meaningless or even farcical. It would help liberate the struggle of the Tibetans from the tragic and tiring role it has come to play as a pawn of appeasement or threat in Great Power rivalries.

The World Wars began as conflicts of identity and ethnicity. It is incumbent to remember that a cause like Tibet which has for too long functioned as a pawn of convenience in international politics is occurring in a geographic region that in itself is a powder-keg that could not be easily diffused if it were to blow up. A challenge is prepared for and can be managed. A threat, on the other hand, usually demands a response, which generally does not offer the leeway of a leisurely considered action. To cultivate the Tibetan plateau (and the Andamans) and position it as central in India’s strategic calculus, then, may be a way to recognize an imminent challenge and get ahead of it before it morphs into becoming a strategic threat that may need to be answered, uncomfortably.

© Greta Sykes