Poet, writer and artist Greta Sykes has published her work in many anthologies. She is a member of London Voices Poetry Group and also produces art work for them. Her new volume of poetry called ‘The Shipping News and Other Poems’ came out in August 2016. The German translation of her book ‘Under charred skies’ has now been published in Germany under the title ‘Unter verbranntem Himmel’ by Eulenspiegel Verlag. She is the chair of the Socialist History Society and has organised joint poetry events for them at the Poetry Café. She is a trained child psychologist and has taught at the Institute of Education, London University, where she is now an associate researcher. Her particular focus is now on women’s emancipation and antiquity. Twitter: @g4gaia. Facebook.com/greta.sykes. German Wikipedia: Greta Sykes.

Poet, writer and artist Greta Sykes has published her work in many anthologies. She is a member of London Voices Poetry Group and also produces art work for them. Her new volume of poetry called ‘The Shipping News and Other Poems’ came out in August 2016. The German translation of her book ‘Under charred skies’ has now been published in Germany under the title ‘Unter verbranntem Himmel’ by Eulenspiegel Verlag. She is the chair of the Socialist History Society and has organised joint poetry events for them at the Poetry Café. She is a trained child psychologist and has taught at the Institute of Education, London University, where she is now an associate researcher. Her particular focus is now on women’s emancipation and antiquity. Twitter: @g4gaia. Facebook.com/greta.sykes. German Wikipedia: Greta Sykes.

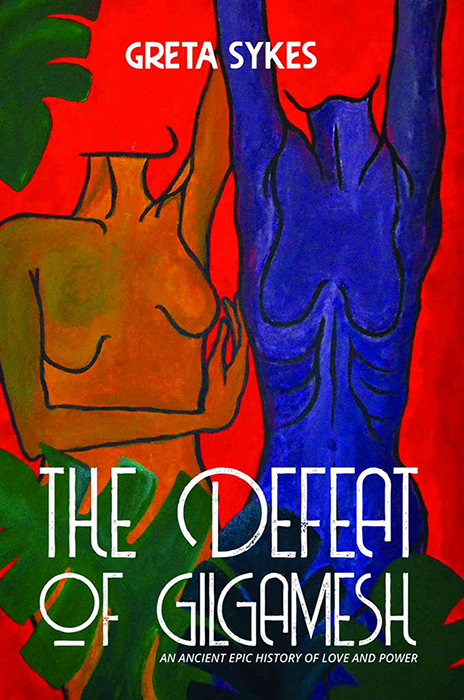

THE DEFEAT OF GILGAMESH

An ancient epic history of love and power by Greta Sykes.

Available at https://www.gretasykes.com/

Amazon, bookshops and publisher https://www.austinmacauley.com/book/%C2%A0defeat-gilgamesh

The feathered punk angel and the sisters

The music resonates in my ears from the instruments played by the rose and ochre coloured angels. But who is the shadowy dark green, feathered figure with a cockerel’s comb, like a punk, who lurks amongst them? His ringed fingers also hold a musical instrument. Erna and I are visiting Grünewald’s Isenheimer Altar in Colmar, painted during the time of the Great Plague. It had ravaged the lives of local families. The torment was so unbearable that the priests attempted to bolt. Matthias Grünewald, a local artist, had been asked to paint the altar pictures. Perhaps the display of suffering could soften the pain of the people. His distorted figures with their swollen bellies would even move a stone to tears and thus ease the lonesome pain of the plague ridden victims.

The music resonates in my ears from the instruments played by the rose and ochre coloured angels. But who is the shadowy dark green, feathered figure with a cockerel’s comb, like a punk, who lurks amongst them? His ringed fingers also hold a musical instrument. Erna and I are visiting Grünewald’s Isenheimer Altar in Colmar, painted during the time of the Great Plague. It had ravaged the lives of local families. The torment was so unbearable that the priests attempted to bolt. Matthias Grünewald, a local artist, had been asked to paint the altar pictures. Perhaps the display of suffering could soften the pain of the people. His distorted figures with their swollen bellies would even move a stone to tears and thus ease the lonesome pain of the plague ridden victims.

The train sped from Karlsruhe to Colmar almost weightlessly as if flying with the geese along sandy acres, winter vegetable fields and distant blue hills. Erna is my older sister. She has an irresistible desire to teach me as if I was twelve years old. She laughs with her eyes almost closed and her painted lips wide in an exaggerated display of great amusement, whether shared by me or not.

‘Sic nos rodunt omnes gentes.’ Erna chatted, mingling the occasional Latin phrase into her speech, like a diamond you want to show off. She had a habit of turning her whole face frontally towards mine Shiva like, her face a mask, both of us embroiled in a dance for survival, or perhaps to escape childhood. Her black contoured green eyes were trying to gaze into my face, catching me out, like an insect in a Venus flytrap. She is beautiful and exotic, I thought, like one of those plants that, as a small insect you want to keep away from. I felt irritated by feeling like a child impulsively disobedient and ready to escape. At one point she said exasperatedly:

“Could you turn to look at me and also move your hair aside a little, so that I can see your face.” She was spoiling my peaceful enjoyment of the landscape, and I stubbornly continued to eye the fields. After a while she suddenly exclaimed: “What beautiful hands you have, such long fingers, so graceful and artistic.” She smiled deceptively. I wondered when the unpleasantries were going to start, I mused and felt caught in judgments, like a bird in a cage. Extra bars could be placed on it any moment. She was sitting very upright close to me making sure I was not straying elsewhere.

I kept my eyes firmly fixed on the ebbing hills and meagre green shoots of the winter wheat, while part of my brain lit up pictures of Hἂnsel, Gretel and the witch in the forest. Is she going to come out and ask me to show my finger to see if I was fat enough?

Thoughts like these intermittently ruffled my mind, but mostly I thought of this strange man called Gruenewald. An experienced multi-media artist in water art, soap making and fine art Gruenewald’s life story remains to this day shrouded in the mists of the past. He lived through the turn of the fifteenth to the sixteenth century and worked at the time of other great modernisers of painting who came under the influence of the Reformation, like Albrecht Duerer, Hans Holbein and Lucas Cranach. His Isenheimer Altar painted to give relief to those suffering from the plague or ‘Johannisfeuer’ is one of those pieces of art that every school child in Germany was taught about with great reverence and awe. Some call Gruenewald the stormiest of all artists who ‘produced a tornado of unbridled art that pulsates past us and drags us into its current’.

We reached Colmar, the medieval town huddled in the Elsass under a bright and cold February sky. Suddenly we were in the tiny museum chapel in front of the altar. Blood red robes drape the figures that seem to relate to each other in a kind of trance dance. They look as if they are unsuccessfully attempting to move away from an endlessly bleak, forlorn land with just shadows suggesting light. The wasted pale yellow and green tinged body of Christ, coloured all over with faint marks, suggestive of the plague, hangs in front of us with his head sunk on his chest. Over there stands John the Baptist tall and imposing and as if he is reflecting on the desperate scene he is witnessing. With an evocative gesture that seems to say ‘learn from this’ his hand is raised towards the figure at the cross with his long finger pointing at the dying Christ, giving a lesson in sorrow and pity.

“Someone told me the red drapery of the cloth is meant to be a symbol of the tongue,” Erna whispers into my ear.

“Why the tongue?” I mutter. The expressive folds of wine coloured cloth seem more a symbol of passion and love, than eroticism. We meander to and fro amidst the visitors to look at other aspects of the Altar. Each panel is presented separately, so that it can be viewed individually.

“I want to find the feathered angel,” my sister demands, pointing at the green punk figure on the exhibition flier.

“I think it is this one,” I reply wondering why she is keen on him. His dark presence amongst the joyful musicians is disturbing. There is an eerie sense of foreboding in his thickly furred body, his feathered arms, his huge olive coloured wings, his querying glance into the heavens. Everything is thrown into question in his look. Hidden cloven hoofs come to mind. Erna leans into the painting for a closer glance. For a moment she seems to become the punk angel with his reddish high toupee like a cock’s comb. Is her hair not also wound into a high reddish toupee? My stomach tightens. We move to another altar scene.

“Do you think this is a cradle?” she asks me, pointing to an item next to the joyous Mary holding her newborn baby in its rags of cloth.

“I think it’s her bed”, I reply. I am lost in the haunting and fragile depiction showing Mary in the intimacy of her bedroom with the water butt and a chamber pot present. Erna is determined to argue about the bed. She wants it to be a cradle. Her face closing in on mine Lucifer like and, with a devilish grin, she murmurs:

“We are slandering! I think we are upsetting these people here.” She looks triumphantly around herself, relishing the conspiracy, as if the other visitors were to be despised for their innocence. Despi-sed, my mind hums Handel. Had the feathered punk angel stepped out of the canvas? On another panel called ‘Saint Anthony’s temptation’ the old man is tugged along the murky ground by his hair. His facial expression shows him yelling with pain and fear at the sight of the nightmarish beasts who threaten him with claws, clubs and fangs. All around him pock marked monsters and reptiles peer out of the darkness at him, while a desperate plague ridden sick man with a swollen belly and open wounds leans into the corner of the painting, ready to give up his soul.

The altar was exhausting and we needed a break. I was relieved to see the ordinary stone pavement and street signs outside, as if we had made a lucky escape. We found an open café. We chatted about the sights and had soup and tea. I wondered why she had not mentioned that she had already visited the exhibition with our sister Marta.

‘You’ve already seen the exhibition with Marta, haven’t you?’

“How do you know?” she asked sharply, as if I had betrayed a confidential secret.

“I talked to her the other day,” I replied nonchalantly.

She continued to make conversation and ignored my question. I was not going to let her off the hook that easily and asked her again directly, addressing my sister Marta’s health issues.

“How was she, when you saw her?”

“She has suffered, so I just let her talk. She wanted to tell me a lot of things.”

When I spoke to my sister Marta recently about Erna she also told to me that she had just listened, because Erna needed to talk a lot. By now we were rushing back to the station in the growing darkness. She continued.

“I don’t want to talk about her. She behaved very badly at my husband’s funeral. I can’t forgive her for that.”

I began to feel sad for her. She seemed so lonely. She had not seen Marta for many years. Her contact with our sister Ulla had also broken off. Her husband was dead, her children far away in other countries. The terrifying dog- and frog-eyed reptiles started to lurk in the shadows of the waning light. I tried to find reassuring reasons for the lonely and angry feelings plaguing her, that did not involve blaming our sisters.

“Maybe, it was the men in your lives that stopped you getting on with each other. “

I am thinking of the jealous intrigues caused by a man who had first wooed Erna, the oldest, only to change his mind and choose a younger one.

“No, it wasn’t,” she retorted sharply.

“I just did not get on with mother. She could not handle me. Did you know that when our mother was pregnant with Ulla, they gave me away to a children’s home for two months. When I was brought home again, I had lost all my speech and my hair. I was weak and feeble!”

We are close to the station at last. So here was one of the dark secrets she had harboured all these years. Erna as a victim. I shuddered but could hardly believe it. It was all the fault of our mother who was long in her grave! She knew how fond we were of our mother, a generous and kind person. My stomach crunched tightly. I saw the feathered punk angel raise his huge bronze wings and fly off into the night contemptuously. She added:

“I never got on with mother. She found me too difficult. She was not intelligent enough for me.”

That remark grazed me as if with cut glass. My mother became kneeling Mary Magdalena with her beautiful hair holding her clasped hands high in utter misery. My sister Erna a wounded, neglected child? Hardly. Her disdainful and vain behaviour just a façade? What was the hidden truth behind the deceptive mask-like smile she kept pushing into my face? Soon enough we were seated in the flying train amidst the darkening landscape. Hills, fields, pylons rushed by and so did the dark shadows from the stories of the family’s past, like Grünewald reptiles with cold, glassy frog’s eyes, horns and claws. I wondered about the lonely anguish she had harboured all these years. Idle reptiles from Grünewald’s temptation walked past the glass door of the compartment of the train. Lucifer’s comb shone. I tried an appeasing smile towards her in an attempt to soothe her brittle feelings but was met by a stony glare. My eyes returned to the fading hills outside with a wish to banish the ghosts from the past when she suddenly hissed in my ear: “You have mother’s mouth.”

‘I have my own mouth,’ I replied stupefied by her spiky outburst. Her obsessive studying of my face had enclosed me in a prison of her past. I had become the bad mother who had sent her child into exile. A frozen moment in her life a long time ago was transformed into molten lava, as she tried to lure me into her past. I turned to look at her. Her pale-reddish hair rose high above her forehead. Her eyes were cold and bland, her mouth had closed down. The huge amused smiles were gone. Who was the fallen angel now? The fallen angel with the cock’s comb sat next to me enticing me to feel guilty. Her mental image of the past had nothing to do with me. I had become wise to the games she was playing. I shrugged my shoulders internally. I decided to ignore her and all the glassy eyed reptiles. I pondered how she could be a badly behaved child who wanted me to be the cruel mother. But that was a game I was not prepared to play.

© Dr Greta Sykes