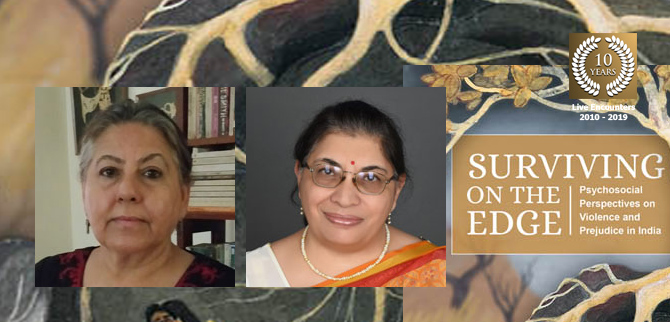

Shobna Sonpar is a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist based in New Delhi.

Neeru Kanwar is a practising psychotherapist and counsellor based in New Delhi.

Published by SAGE – https://in.sagepub.com/en-in/sas/surviving-on-the-edge/book269161

A plural society inevitably faces challenges to harmony arising from contestations over issues of resources, power and identity. In the midst of rapid social and technological change with the world becoming globalised, with increasingly porous borders between people and ideas, with traditional hierarchies of gender, class, caste and ethnicity being upturned, there is the paradoxical rise of groups and movements that are more ‘localised’ and insular. Seeking to assert their distinctiveness and superiority, they espouse attitudes and behaviours that reject, exclude and vilify persons perceived to be outsiders to their community or nation. Often they lay claim to power in ways that are regressive and violent. At its worst this xenophobia manifests in hate crimes.

A plural society inevitably faces challenges to harmony arising from contestations over issues of resources, power and identity. In the midst of rapid social and technological change with the world becoming globalised, with increasingly porous borders between people and ideas, with traditional hierarchies of gender, class, caste and ethnicity being upturned, there is the paradoxical rise of groups and movements that are more ‘localised’ and insular. Seeking to assert their distinctiveness and superiority, they espouse attitudes and behaviours that reject, exclude and vilify persons perceived to be outsiders to their community or nation. Often they lay claim to power in ways that are regressive and violent. At its worst this xenophobia manifests in hate crimes.

The tension between belonging to a plural and diverse whole while sustaining a cherished sense of distinctiveness is a ubiquitous challenge based on the opposing human needs for belonging and for differentiation. The theory of optimal distinctiveness posited by the social psychologist Brewer holds that we identify with groups which satisfy our need to assimilate and belong but which are also sufficiently distinct from other groups to satisfy our need for distinctiveness. The clarity of boundaries between the two serves to secure both inclusion and exclusion. One way that such boundaries are maintained is through the beliefs and practices that govern norms of social distance.

Another layer to the tension described above is how individuals construct sameness and difference in order to affirm their own identity.

Othering, the process of perceiving and portraying something as fundamentally different and alien to oneself, enables people to differentiate Self from the Other, the in-group form the out-group, in ways that affirm and protect the Self. Self-regard can come to depend on the denigration of the other group even as the despised group becomes the receptacle of qualities disavowed by the Self.

These processes result in various forms of exclusion . It is evident at the resource level where many are excluded from sharing material resources to the extent of poverty and deprivation. It is evident at the social level in the practices of social distance, the operation of stereotypes, prejudice and stigma. Significantly, social exclusion also determines the boundary of our moral community, those whose suffering is recognized and who fall within the scope of justice. Moral inclusion is characterized by considerations of fairness for those falling within the community, sharing resources with them and extending efforts for their well being. Moral exclusion is characterized by lack of concern and responsibility towards those outside, positioning them as undeserving and inferior. This sets the grounds for dehumanization. Race, gender, caste, class, sexual orientation, disability, nationality, ethnicity, religion have all served as markers differentiating those within from those outside the moral community.

Prejudiced attitudes and beliefs about other groups and norms for conduct towards them that are discriminatory, devaluing and exclusionary form the base of a pyramid of violence. The stereotypes and prejudices that make up the base are often culturally congruent and normalized and therefore not acknowledged as forms of violence. At the top of the pyramid are actual acts of physical violence – acts of murder, rape, mutilation, lynching .Perceived threat is the central factor in escalating prejudiced attitudes to acts of violence such as hate crimes. The threat may be realistic such as competition for jobs, scarce resources or territory. But often the perceived threat is a symbolic one to people’s social identities, their culturally important values and norms, their ‘way of life’.

The threads that connect the dramatic instances of violence to the mundane, normalised and hence invisible forms of exclusion and discrimination indicate the importance of examining how social and psychological processes drive feelings, attitudes and behaviours towards greater malignancy.

The book ‘Surviving on the edge: Psychosocial perspectives on violence and prejudice in India’ is a collection of essays, experiential accounts and case studies originally published in Psychological Foundations – The Journal. These articles are written primarily but not exclusively by psychologists and other mental health practitioners. While it is sometimes thought that the particular interest that psychologists take in the voices of individuals and their inner reality implies a disregard of social and cultural influences, it is to be noted that the stories of suffering heard in the clinic are also a reflection of the discriminatory and violent world in which we live. What is within the individual psyche is also ‘social’ because people internalise social norms as a part of their subjectivity and such ‘normative unconscious processes’ evoke thoughts, feelings and behaviours consonant with social norms. Hence the use of the term ‘psychosocial’ which explicitly recognizes that all behaviour results from the interaction of factors lying within individuals, within their interpersonal and group relations and also within the larger, social, political and cultural context.

The volume does not offer a comprehensive account of theory and research, nor is it exhaustive of all categories of prejudice, discrimination and violence. What it does provide is a stance that is experience-near, a position that deepens understanding by making the subject a human one. It also tends towards a process view looking at the ways in which the base of the violence pyramid -prejudiced and exclusionary attitudes and behaviours – is constructed and the sites of such socialisation including the family.

The book is in two sections. The first section maps some of the terrain marked by violence and prejudice and the second section considers the impact of prejudice and violence on wellbeing and the amelioration of such impact. Gender-related discrimination and violence are well researched areas especially from feminist-led understandings of power and gender inequities. The related contributions in this volume suggest that the complexity of real life warrants exploration into other dimensions that feed into discrimination and violence as well as the ways in which oppressive gender socialisation is escaped. The theme of ethnicity and religion is another area addressed by some papers in the volume -the tensions between the personal self and socio-cultural identity, the ways in which our location in particular class, caste, race and ethnic identity blinds us to how we participate in discriminatory and exclusionary practices, and the way that social-religious identity becomes hyperconscious when under attack. Disability, mental and physical, is another sector where stigmatisation and consequent devaluation operate. The articles in the volume interrogate the legitimisation and perpetuation of stigma of disability through society’s ideological systems and institutions.

The second section of the volume addresses the impact of prejudice, exclusion and violence. The idiom of trauma is often used to talk about the nature of suffering following situations of prolonged deprivation and victimization as well as extreme situations of disaster and violence. The articles span the issue of trauma and ameliorative interventions in contexts of sexual violence, political conflict , terrorism, and riots. The articles also underline the abundant evidence of resistance, resilience and even ‘adversity-activated’ personal development. While liberation from the tyranny of prejudiced ways of relating to the world can lie in the practice of self-reflexivity and the development of personal aspects of selfhood, several illuminating examples of work on the ground demonstrate the range of interventions possible to deal with such trauma.

Taken together, the essays in this volume offer a psychosocial perspective on prejudice and violence that is close to the complexity of lived experience and ground realities.

© Shobna Sonpar and Neeru Kanwar