The Competition for Outer Space Resources and the Role of Middle Powers

by Dr Namrata Goswami

Dr. Namrata Goswami is an author, strategic analyst and consultant on counter-insurgency, counter-terrorism, alternate futures, and great power politics. After earning her Ph.D. in international relations, she served for nearly a decade at India’s Ministry of Defense (MOD) sponsored think tank, the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), New Delhi, working on ethnic conflicts in India’s Northeast and China-India border conflict. She is the author of three books, “India’s National Security and Counter-Insurgency”, “Asia 2030” and “Asia 2030 The Unfolding Future.” Her research and expertise generated opportunities for collaborations abroad, and she accepted visiting fellowships at the Peace Research Institute, Oslo, Norway; the La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia; and the University of Heidelberg, Germany. In 2012, she was selected to serve as a Jennings-Randolph Senior Fellow at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), Washington D.C. where she studied India-China border issues, and was awarded a Fulbright-Nehru Senior Fellowship that same year. Shortly after establishing her own strategy and policy consultancy, she won the prestigious MINERVA grant awarded by the Office of the U.S. Secretary of Defense (OSD) to study great power competition in the grey zone of outer space. She was also awarded a contract with Joint Special Operations University (JSOU), to work on a project on “ISIS in South and Southeast Asia”. With expertise in international relations, ethnic conflicts, counter insurgency, wargaming, scenario building, and conflict resolution, she has been asked to consult for audiences as diverse as Wikistrat, USPACOM, USSOCOM, the Indian Military and the Indian Government, academia and policy think tanks. She was the first representative from South Asia chosen to participate in the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies NATO Partnership for Peace Consortium (PfPC) ‘Emerging Security Challenges Working Group.’ She also received the Executive Leadership Certificate sponsored by the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, National Defense University (NDU), and the Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies (APCSS). Currently, she is working on two book projects, one on the topic of ‘Ethnic Narratives’, to be published by Oxford University Press, and the other on the topic of ‘Great Power Ambitions” to be published by Lexington Press, an imprint of Rowman and Littlefield.

Outer-space is changing given the visible and growing discourse in developed nations about trillions of dollars of space-based resources, waiting to be harvested, to include Platinum, Titanium, Solar Power.

This discourse is a departure from the Cold War ‘Space Race’ between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R, when getting somewhere first in space was critical for purposes of prestige and reputation.[1] Today, the space discourse aims to develop competence in technology to generate profit by investing in future projects like Space-based Solar Power (SBSP), asteroid mining, and lunar presence. Space is becoming as much a private sector enterprise as it is state driven. U.S. based companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, Planetary Resources, Deep Space Industries, Chinese-based companies like OneSpace, Tencent, LandSpace, and Indian based companies like ReBeam, Bellatrix, TeamIndus, Astrome, are pushing for legislation that enables private sector investments in space

Consequently, the U.S. Congress passed the “U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act” in 2015, offering its citizens ownership over space resources on a ‘first come, first serve’ principle.[2] In China, there is interest in establishing similar legislation. India released its draft “Space Utilities Bill” in 2017 to regulate and encourage private investments.[3] Significantly, China is investing in space resource capabilities like asteroid mining, SBSP, especially aimed at making China the most advanced country in space technology by 2045.[4] India follows close behind, with its former President Abdul Kalam stating that only after harvesting space resources can India truly develop. In 2018, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi committed India to a human space program aimed at accomplishing feats leading to permanent space presence.[5]

With Commerce follows Military Innovation

History informs us that commerce led to military innovation for maintaining free access and safe passage. The development of the British Royal Navy and the U.S. Navy, including the reestablishment of the Marine Corps, whose main task was to fight the Barbary pirates in Tripoli and Algiers, reflects this.[6] With growing commercial interests and military assets in space, Chinese President Xi Jingping directed China’s Strategic Support Force (SSF), established in 2015, tasked with ‘space and cyber’, to innovate and develop to support China’s growing presence in space.[7] In response, U.S. President Donald Trump announced the establishment of a ‘U.S. Space Force’ in June 2018, to respond to the rising challenges of space dominance/industrialization, and military innovations by China and Russia.[8] The Pentagon released a report soon after, detailing how the ‘Space Force’ will be established.[9] The absence of clear regulatory frameworks, anticipating this space-based economy, implies the need for additions to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST) that does not offer clear provisions in this regard. Luxembourg is the only country to establish legislation to regulate asteroid mining and create a sovereign fund that can attract private space companies to set up shop.[10] However, to argue that this growing economic competition would lead to militarization of outer-space is missing the point. Space is already militarized with military space satellites, Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) paths, and Anti-Satellite Weapons (ASAT) technology. Wang Cheng, a Chinese intellectual, noted in an article titled, “The US Military’s ‘Soft Ribs,’ A Strategic Weakness,” in 2000 that, “For countries that can never win a war with the U.S. by using the method of tanks and planes, attacking the U.S. space system may be an irresistible and most tempting choice.”[11] China’s 2007 ASAT test (a decade ago), alerted the world to potential Chinese threats to their satellites.

Significantly, the OST ensures that “States shall not place nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies or station them in outer space in any other manner’.[12]

While the OST states that “Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means,”[13] it also affirms in article 1 that “Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall be free for exploration and use by all States…”[14] and further requires that “The activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty…” [15] In that context, the U.S. claims that asteroid mining constitutes merely ‘use’ and involves no claim of sovereignty over either space or a celestial body. To comply with the provision of authorization and continuing supervision, the U.S. Congress has written laws stating, “A United States citizen engaged in commercial recovery of an asteroid resource or a space resource under this chapter shall be entitled to any asteroid resource or space resource obtained, including to possess, own, transport, use, and sell the asteroid resource…”[16] Similarly, Luxembourg’s law states, “authorisation shall be granted to an operator for a mission of exploration and use of space resources for commercial purposes upon written application to the ministers.”[17] The International Institute of Space Law Position Paper states, “Therefore, in view of the absence of a clear prohibition of the taking of resources in the Outer Space Treaty one can conclude that the use of space resources is permitted. Viewed from this perspective, the new United States Act is a possible interpretation of the Outer Space Treaty. Whether and to what extent this interpretation is shared by other States remains to be seen.”[18]

That said, conflict could break out if two countries (say U.S. and China) arrive at an asteroid rich in resources and claim ownership based on ‘first come, first serve’. What then?[19] There is no established regulatory authority that can adjudicate in such a dispute. We know that the U.S. military is constitutionally obligated to come to the assistance of U.S. military and commercial assets if it is threatened by an adversary. The U.S. Commercial Act said as much, “It is the sense of Congress that the Department of Defense plays a vital and unique role in protecting national security assets in space.”[20] The lack of legal clarity in these matters requires urgent intervention as the position of the U.S., Luxembourg is disputed by some. The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) should begin the process of adding protocols to the OST, perhaps in line with The Hague International Space Resources Governance Working Group’s draft proposal,[21] given the large-scale entry of the private sector into space. We must avoid repeating the mistakes of the past when private trading organizations like the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company undertook excessive commercial exploitation, without any regulatory mechanisms in place, to the devastation of the colonies. Ideas of space colonization is relevant here as policy makers have framed the discourse as such. For instance, Ye Peijian, head of China’s Lunar Mission stated that [t]he universe is an ocean, the moon is the Diaoyu Islands, Mars is Huangyan Island. If we don’t go there now even though we’re capable of doing so, then we will be blamed by our descendants. If others go there, then they will take over, and you won’t be able to go even if you want to. This is reason enough.[22] Elon Musk, founder of SpaceX has pushed for plans to colonize Mars stating, “It’s important to get a self-sustaining base on Mars because it’s far enough away from earth that [in the event of a war] it’s more likely to survive than a moon base.”[23]

In this context, countries like UAE and Luxembourg can influence regime construction that ensures that ‘Middle Powers’[24] take advantage of the future space economy. I define Middle Powers as those states in the international system that locate below a super-power or a major power, but with enough power, capacity and influence at their disposal to shape international regimes and events. These powers utilize their constitutive capacities, especially through their foreign policy behavior, to not only create global norms and standards of behavior, but also add legitimacy to international regimes through their support. In my estimation, both UAE and Luxembourg are Middle Powers. The role of Middle Powers is likely to grow in the realm of outer-space. After all, the U.S. commercial act does privilege, “first come, first serve”, with an implicit assumption that those who arrive first will be American citizens. Hence, the key question is how to develop a framework that ensures profit sharing of a global common, given the range of resources in outer-space.

UAE and Luxembourg

While Great Power (U.S, China, India) actions may be primary drivers on space, their actions take place against a tapestry of institutions, norms and receive approval or approbation of a larger international society which may decide the legitimacy or illegitimacy of such actions. As Middle Powers, both UAE and Luxembourg appreciate the possibility of space resources to shift resource availability and control with implications for changes in global power.[25] Each is constructing their approach to this under-governed and contested region according to their own unique cultural context and preferences.

UAE

In 2014, UAE announced the establishment of its space agency with the explicit aim to develop UAE as the regional hub for outer space activities in the Middle-East.[26] The UAE Space Agency seeks to help resolve global issues of natural disasters and share space expertise to mitigate the problems arising from shrinking resources and climate change. The Mohammad Bin Rashid Space Center (MBRSC), the commercial satellite communication companies, Thuraya and Al Yah Sat, are taking the lead in this domain. By end of 2019, the UAE Space Agency and Exolaunch will jointly launch the MeznSat, a satellite developed by students from the American University of Ras Al Khaimah and Khalifa University. MeznSat will monitor and measure the methane and carbon dioxide levels in the UAE’s atmosphere.[27] According to Dr Mohammed Al Ahbabi, the Director General of the UAE Space Agency “The MeznSat project falls within the framework of the UAE Space Agency’s strategy, which aims to develop Emirati capacities and expertise and support scientific research”.[28]

One of UAE’s major space project is its Mars Mission, named “Hope Probe”, an indigenously built spacecraft that will orbit MARS and study its climate and atmosphere by 2021.[29] 2021 is significant for the UAE as it marks the 50th year of its establishment, and the Hope Probe is planned to utilize space in that celebration. On April 22, 2019, the UAE Space Agency and the MBRSC issued a statement that the Hope Probe was 85 per cent complete. Director-General of the MBRSC, Yousuf Hamad Al Shaibani, asserted that, “Completing 85 per cent of the Hope Probe in this short period was a great challenge that we overcame through the guidance of our wise leadership and the efforts of our youth. The UAE has reached an advanced stage in achieving our wise leadership’s vision to reach the Mars orbit by December 2021”.[30]

One of UAE’s major space project is its Mars Mission, named “Hope Probe”, an indigenously built spacecraft that will orbit MARS and study its climate and atmosphere by 2021.[29] 2021 is significant for the UAE as it marks the 50th year of its establishment, and the Hope Probe is planned to utilize space in that celebration. On April 22, 2019, the UAE Space Agency and the MBRSC issued a statement that the Hope Probe was 85 per cent complete. Director-General of the MBRSC, Yousuf Hamad Al Shaibani, asserted that, “Completing 85 per cent of the Hope Probe in this short period was a great challenge that we overcame through the guidance of our wise leadership and the efforts of our youth. The UAE has reached an advanced stage in achieving our wise leadership’s vision to reach the Mars orbit by December 2021”.[30]

Interestingly, the UAE space program is advertised as the “first Arab, Islamic probe to reach MARS by encouraging the peaceful application of space research”.[31] Minister of State for Higher Education and Advanced Skills and Chairman of the UAE Space Agency, Dr Ahmad Belhoul Al Falasi specifies:

The UAE is on the verge of making history, after turning its dream of becoming the first Arabic and Islamic country to send a spacecraft to Mars into reality. This monumental endeavour is the culmination of the efforts of a skilled and experienced team of young Emiratis who, with the support of the nation and its visionary leadership, will secure the UAE’s position at the forefront of space exploration.[32]

According to the UAE’s Ambassador to the United States, Yousef Al Otaiba, “This is the Arab world’s version of President Kennedy’s Moon shot – it’s a vision for the future that can engage and excite a new generation of Emirati and Arab youth”.[33] In October 2015, the UAE space agency became a member of the International Space Exploration Coordination Group (ISECG).[34] Dr. Mohammed Al Ahbabi, Director General of the UAE Space Agency, specifies, “certain countries might have problems here on Earth, but you will see them cooperate in space”.[35] UAE is starting to play a prominent role in the UN’s Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) and by hosting several international meetings and conferences on space law and policy. Through its membership in ISECG and U.N. space forums, the UAE can bring about substantial influence to construct this future space regime relevant to a resource-based future of space, especially to ensure that future is based on cooperation.

In March 2019, the UAE adopted its National Space Strategy 2030, in a meeting chaired by Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai. The National Space Strategy 2030 is ambitious, and it includes investments on space manufacturing, assembly, space science and research, as well as commercial space. Critically, the UAE also commited to establish a space regulatory framework, which includes four components: National Space Policy, Space Sector Law, Space Regulations, and National Space Strategy.[36]

Luxembourg

Luxembourg’s prominence in encouraging exploitation of space resources is growing. In June 2016, Luxembourg established a $227 million fund to attract companies focused on asteroid mining.[37] It became the first European country to develop a legal framework (like the 2015 US Asteroid Act) to adjudicate the commercial exploitation of space resources. In 2016, its Ministry of Economy announced the establishment of the Space Resources Initiative (SRI), whose role “will be the development of a legal and regulatory framework confirming certainty about the future ownership of minerals extracted in space from Near Earth Objects such as asteroids.”[38] The SRI website states that Luxembourg aims to establish itself as a European hub (similar to UAE’s goal for the Middle-East), in the “exploration and use of space-based resources”.[39] Luxembourg has a draft law that states that companies can keep the resources they have mined. This positive atmosphere has drawn asteroid mining companies like U.S. based Deep Space Industries, Planetary Resources and Japanese company, iSpace, developing lunar landers, to open shop in Luxembourg. Luxembourg is already cooperating with Deep Space Industries (now re-branded as Bradford Space Inc. after it was bought up by Bradford Space) on its Prospector X mission that aims to use a nano-spacecraft to test its asteroid technologies. To add to its institutional capacity, Luxembourg established its Space Agency on September 12, 2018, especially aimed at Space Resources. Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of the economy, Étienne Schneider, announced that “The agency will be well-equipped to support industry in their daily challenges, and it leads to the most favorable environment for this sector to continue to grow”.[40] He announced the creation of $116 million Luxembourg Space Fund. In May 2019, Luxembourg and the U.S. signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to deepen cooperation on tackling space debris, defense, space commerce and regulation. Significantly, Luxembourg has signed space cooperation agreements with China, Japan, UAE, Brazil, Poland, Belgium, the Czech Republic.[41]

Luxembourg’s penchant for understanding the lucrative nature of outer space was vindicated by its early intervention in communication satellites. In the 1980s, when the space commercial satellite industry was still in its early days, Luxembourg passed legislations and invested heavily in its homegrown space company, Société Européenne des Satellites (SES), which enabled it to thrive and enjoy revenues to the tune of 2 billion Euros in 2015.[42] Consequently, Luxembourg is taking deliberate constitutive actions, contextually situated within the futuristic space-resources discourse, taking advantage of its state capacity rooted in high GDP Per Capita growth rates ($104, 103.00).[43]

The question that bears some significance is: In this scenario of growing interest in space industrialization, mining, and space presence, how can countries like Luxembourg and UAE ensure shared benefits from the future space economy?

Here are a few recommendations: –

- Lead the world in passing progressive national space law to establish compatible norms for space resources.

- Organize global capital through large investment funds and bank loans for space development.

- Organize global talent through innovation prizes (as is happening through the UAE’s UAV and space challenges).

- Offer to host global organizations for space governance (the Space Equivalent of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) to ensure safety of navigation,

- Space governance issues such as active debris removal, insurance reform, space traffic management, and frequency and slot allocation for Solar Power Satellites are likely to be ill-perceived if initiated by any of the major spacefaring powers, but if initiated and moderated by Middle Powers, competition between the Major Powers can be managed.

- Level up Luxembourg and UAE’s brand in renewable energy by investing in ideas like Space Based Solar Power.

Interestingly, very similar to China employing its space program as a critical part of its China dream, and ambitions of utilizing space for the 100th year anniversary of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) – 2049, UAE is broadcasting its Mars program as a celebration of the 50th year of its establishment (2021). Curiously enough, 2021 is also the year that China will utilize space to celebrate the 100th year establishment of the Communist Party of China (CPC).[44] What I find fascinating in these narratives that space achievements especially those that seek space industrialization and space commerce are broadcasted as celebratory projects by this major and middle space powers.

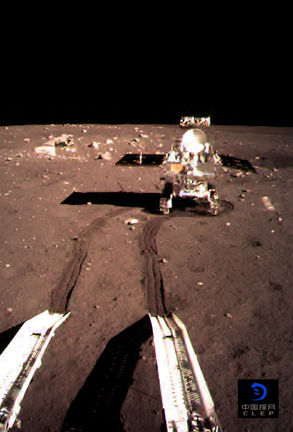

The game has changed: from the days of Apollo and Sputnik, when getting somewhere first in space and then returning to earth, was viewed as offering great prestige. We are in the age of Chang’e 4: when achieving space presence and industrialization are seen as offering great economic benefits and the resultant prestige that comes with that.

1Robert Hackett, “Asteroid Passing Close to Earth Could Contain $5.4 Trillion of Precious Metals”, Fortune, July 20, 2015 at http://fortune.com/2015/07/20/asteroid-precious-metals/ (accessed September 14, 2018).

[2] “U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, 2015,” H.R. 2262, 114th Cong, 2015-2016 at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2262/text (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[3] Aswathi Pacha, “The Hindu Expalins: What is the Space Activities Bill, 2017”, The Hindu, November 23, 2017 at https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/science/the-hindu-explains-what-is-the-space-activities-bill-2017/article20680984.ece (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[4] Mia Chi, “China Aims to be World-Leading Space Power by 2045”, China Daily, November 17, 2017 at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2017-11/17/content_34653486.htm (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[5] Michael Safi, “India Aims to Send Astronauts into Space by 2022, Modi Says”, The Guardian, August 15, 2018 at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/15/india-conduct-manned-space-mission-2022-modi (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[6] For more, Max Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace Small Wars and the Rise of American Power (New York: Basic Books, 2002), pp. 3-29.

[7] Xinhua, “Strive to Build a Strong, Modern Strategic Support Force: Xi,” ChinaMilitary, Aug. 29, 2016, http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2016-08/29/content_7231309.htm.

[8] Namrata Goswami, “The US ‘Space Force’ and its Implications”, The Diplomat, June 22, 2018 at https://thediplomat.com/2018/06/the-us-space-force-and-its-implications/ (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[9] “Final Report on Organizational and Management Structure for the National Security Space Components of the Department of Defense,” Department of Defense, Aug. 9, 2018, at https://media.defense.gov/2018/Aug/09/2001952764/-1/-1/1/ORGANIZATIONAL-MANAGEMENT-STRUCTURE-DOD-NATIONAL-SECURITY-SPACE-COMPONENTS.PDF (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[10] Jeff Foust, “Luxembourg Adopts Space Resources Law”, SpaceNews, July 17, 2017 at https://spacenews.com/luxembourg-adopts-space-resources-law/ (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[11] Mark Williams Pontin, “China’s Antisatellite Missile Test: Why?” MIT Technology Review, March 8, 2007, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/407454/chinas-antisatellite-missile-test-why/.

[12] “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”, at http://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, 2015,” n.2.

[17] “Draft Law on the Exploration and Use of Space Resources”, Luxembourg, at https://spaceresources.public.lu/content/dam/spaceresources/news/Translation%20Of%20The%20Draft%20Law.pdf (Accessed September 17, 2018).

[18] International Institute of Space (IISL)“Position Paper on Space Resource Mining”, December 20, 2015, p.3 at http://iislwebo.wwwnlss1.a2hosted.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/SpaceResourceMining.pdf (Accessed September 16, 2018) ; IISL, Directorate of Studies, “Does International Space Law Either Permit of Prohibit the taking of Resources in Outer Space and on Celestial Bodies and How is This Relevant for National Actors? What is the Context, and What are the Contours and Limits of this Permission or Prohibition?”, Background Paper, 2016 at http://iislweb.org/docs/IISL_Space_Mining_Study.pdf (Accessed September 16, 2018).

[19] Namrata Goswami, “Star Wars From Space-Based Solar Power to Mining Asteroids for Resources: China’s Plans for the Final Frontier”, Policy Forum, September 7, 2016 at https://www.policyforum.net/star-wars/ (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[20] “U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, 2015,” n.2.

[21] “The Hague International Space Resources Governance Working Group”, University of Leiden, https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/law/institute-of-public-law/institute-for-air-space-law/the-hague-space-resources-governance-working-group (Accessed September 16, 2018).

[22] “Space: The Next South China Sea,” Maritime Executive, July 13, 2018, https://www.maritime-executive.com/editorials/space-the-next-south-china-sea#gs.8SP=u7U.

[23] Olivia Solon, “Elon Musk: We Must Colonize Mars to Preserve our Species in a Third World War”, The Guardian, March 11, 2018 at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/mar/11/elon-musk-colonise-mars-third-world-war (Accessed on September 16, 2018).

[24] For an interesting perspective on Middle Powers, please see Eduard Jordaan, “The Concept of a Middle Power in International Relations: Distinguishing Between Emerging and Traditional Middle Powers”, Politikon: South African Journal of Political Studies, 30 (1), 2003, 165-181 at https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1393&context=soss_research (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[25] “Luxembourg and the United Arab Emirates Sign MoU on Space Resources”, Space Resources.Lu, October 10, 2017 at https://spaceresources.public.lu/en/actualites/2017/MoU-UAE.html (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[26] Muhammad Bin Rashid Space Center, at https://mbrsc.ae/en/page/aboutus (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[27] Jack Dutton, “UAE Space Agency to Launch Satellite Developed by Students”, The National, May 12, 2019 at https://www.thenational.ae/uae/science/uae-space-agency-to-launch-satellite-developed-by-students-1.860640 (Accessed on May 13, 2019).

[28] Ibid.

[29] “Emirates Mars Mission,” UAE Space Agency, at http://www.emiratesmarsmission.ae/mars-probe (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[30] “Video: UAE’s Hope Probe Bound for Mars is 85 per cent complete”, The Khaleej Times, April 24, 2019 at https://www.khaleejtimes.com/news/general/video-uaes-hope-probe-bound-for-mars-is-85-complete- (Accessed on May 13, 2019).

[31] Muhammad Bin Rashid Space Center, n.26.

[32] “Video: UAE’s Hope Probe Bound for Mars is 85 per cent complete”, n.30.

[33] Taimur Khan, “Mars Mission ‘Arab World’s Kennedy Moon Shot’, Says UAE”, The National, December 3, 2015 at https://www.thenational.ae/world/mars-mission-arab-world-s-kennedy-moon-shot-says-uae-ambassador-to-us-1.103660 (Accessed on September 14, 2018).

[34] “International Space Exploration Coordination Group, “Annual Report 2015”, at https://www.dlr.de/Portaldata/28/Resources/dokumente/rm/ISECG_AnnualReport_2015.pdf (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[35] Thamer Al Subaihi, “UAE Space Programme a Conduit for Cooperation”, The National, November 28, 2015 at https://www.thenational.ae/uae/uae-space-programme-a-conduit-for-cooperation-1.67069 (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[36] “UAE Cabinet Approves National Space Strategy 2030”, Khaleej Times, March 12, 2019 at https://www.khaleejtimes.com/news/government/uae-cabinet-approves-national-space-strategy-2030–12 (Accessed on May 13, 2019). Also see National Space Strategy 2030 at https://www.government.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/federal-governments-strategies-and-plans/national-space-strategy-2030 (Accessed on May 13, 2019).

[37] David Z. Morris, “Luxembourg to Invest $227 Million in Asteroid Mining”, Fortune, June 5, 2016 at http://fortune.com/2016/06/05/luxembourg-asteroid-mining/ (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[38] “Space Resources.Lu”, at https://spaceresources.public.lu/en.html (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[39] Ibid.

[40] Jeff Foust, “Luxembourg Establishes Space Agency and New Fund”, SpaceNews, September 13, 2018 at

[41] “Luxembourg and US Agree to Deepen Cooperation in Space”, Phys.org, May 10, 2019 at https://phys.org/news/2019-05-luxembourg-deepen-cooperation-space.html (Accessed on May 13, 2019).

[42] Atossa Araxia Abrahamian, “How a Tax Haven is Leading the Race to Privatise Space”, The Guardian, September 15, 2017 at https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/sep/15/luxembourg-tax-haven-privatise-space (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[43] The World Bank, “GDP Per Capita (Current US$), at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gdp.pcap.cd (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[44] “China in the New Era: What to Expect in 2021?”, Global Times, December 10, 2017 at http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1079510.shtml (Accessed on May 13, 2019).

© Dr Namrata Goswami