Patron-Client Relationship: Pakistani Deep State and the Jaish-e-Mohammad

by Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray

Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray held the position of Visiting Professor and Indian Council of Cultural Relations (ICCR) chair, India Studies at Murdoch University, Perth between July-December 2017. He served as a Deputy Director in the National Security Council Secretariat, Government of India and Director of the Institute for Conflict Management (ICM)’s Database & Documentation Centre, Guwahati, Assam. He was a Visiting Fellow at the South Asia programme of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang TechnologicalUniversity, Singapore between 2010 and 2012. Routray specialises in decision-making, governance, counter-terrorism, force modernisation, intelligence reforms, foreign policy and dissent articulation issues in South and South East Asia. His writings, based on his projects and extensive field based research in Indian conflict theatres of the Northeastern states and the left-wing extremism affected areas, have appeared in a wide range of academic as well as policy journals, websites, and magazines.

Article republished by permission of http://mantraya.org

Abstract

In the complex jihadi landscape of South Asia, Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) , since its origin in 2000, has served as an instrument of Pakistani military’s policy vis-à-vis India and Afghanistan. The deep state within Pakistan nurtured it in the initial years and used it as an instrument of foreign policy against the neighbouring countries. Barring few years when President Musharraf tried to curb JeM’s activities, such incessant logistical support contributed to the group’s rising profile. Buried in the debate, however, are two important trends that continue to receive less attention. Firstly, the JeM continues to share a symbiotic relationship with the Taliban and al Qaeda; and secondly, Pakistan military continues to adopt a dual strategy of switching between the JeM and the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), to deflect international criticism. A policy to neutralise these groups in Pakistan must factor in ways and means to break this patron-client relationship.

Introduction

It was on a cold wintry evening of 31 December 1999, 31-year-old Masood Azhar walked few steps as a free man on the tarmac of Kandahar airport with a cautious glee, before being whisked away in a jeep by the Taliban. He had spent his last five years in the Kot Balwal prison in Kashmir, since his arrest in 1994. His previous attempt to escape the prison had failed. But the hijacking of the Indian Airlines flight IC814 by a group of Pakistanis who sought to exchange four prisoners in Indian jails, including Azhar, for 155 passengers in the plane, changed his fate. Indian government decided to give in to the demands of the hijackers and Azhar was now free to return to the mujahideen’s career he had chosen in 1989, after passing out of the Binori mosque in Karachi.[2] In less than a year, Azhar, the secretary general of the terrorist group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen (HuM), went on to establish the JeM[3], a formidable terror formation which is believed to share the closest link with the Pakistani military.

Although the JeM, in comparison to other Kashmir-centric and Pakistan based terror formations, is a relatively new outfit, this analysis attempts to provide its contemporary history, focusing on its relations with the Pakistani military establishment. The Pakistani military underplays JeM’s existence and has even denied Masood Azhar’s presence in the country. This paper extrapolates primarily from literature from both Pakistan and India. Indian analysts, over the years, have depended on their unnamed Pakistani sources and inputs by India’s own intelligence agencies to construct their narrative on Indian centric terror formations operating from Pakistan. Very few Pakistanis have been able to visit any of the JeM establishments in the country. So, the dependence of this analysis on unverifiable data and information is higher. This is not an uncommon trend in research on terrorism. Attempt, however, has been made to keep any consequent bias to the minimum by making intelligent choice of sources and cross verification of information derived from them.

Origin, expansion, and network formation

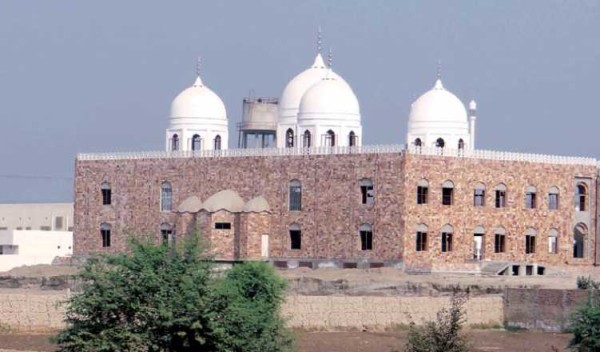

in Pakistan, 2000. Photo Courtesy: BBC

After being released, Azhar’s connections with the Pakistan military, the Afghan Taliban, & al Qaeda combine ensured that the JeM emerged as one of the important Jihadi outfits in Pakistan in quick time. Azhar toured Kandahar to secure the blessings of the Taliban leadership for launching JeM. The HuM was flabbergasted by the formation of the new group and called Azhar “a greedy Indian agent who is out to damage the Kashmiri Jehad”. Azhar delivered speeches in various Pakistani cities and towns and said that his group would eliminate Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee, who he termed as Abu Jahal (one of the key enemies of Prophet Mohammad).[4] Prior to the 9/11 attacks, the JeM was reckoned as one of the two primary jihadi organisations in the country, the other being the LeT. A number of Pakistani media reports narrated the linkages between the JeM and the talked about the help Azhar got from the establishment. For instance, Amir Mir writes, Azhar’s spymasters in Pakistan managed his career well. On one occasion, “he was allowed to travel to Lahore with scores of Kalashnikov-bearing guards”[5].

The outfit set up a training camp in Balakot as well as Bahawalpur sometime in 2000. Initially set up as a facility to churn out Jihadis to fight the United States in Afghanistan, Balakot became a crucial training centre for JeM’s recruits focused on Kashmir. By early 2001, the camp was providing ‘both basic and advanced terrorist training on explosives and artillery’. A secret US Department of Defence cable, released by Wikileaks, mentions a Pakistani national Hafez K Rahman who fought against the US in Afghanistan, had received training from the JeM facility at Balakot. Rahman is a Guntanamo Bay detainee.[6] Another Pakistani national and Guantanamo detainee Mohammed Arshad Raza, a member of Tabligh-e-Jamaat, too had trained at Balakot and claimed to have knowledge of the recruitment practices of the JeM.[7] Khan had been arrested in December 2001 in Afghanistan and released from Guntanamo in September 2004. Similarly, Rashid Rauf, who attempted to bomb a transatlantic flight, passed out from the Bahawalpur camp of the JeM. In 2006, Rauf confessed to his Pakistani interrogators that he arrived in Bahawalpur in early 2002, got in touch with a senior JeM operative Amjad Hussein Farooqi, trained in the Bahawalpur camp and went Afghanistan with Farooqi in mid-2002, before establishing close connections with the al Qaeda.[8] One the perpetrators of the London underground attacks in July 2005, Shehzad Tanweer, had met a JeM leader Osama Nazir during his visit to Pakistan in 2003 and might have undergone training in one of the JeM’s facilities.

Masood Azhar, because of his body weight, was never cut out to be an active fighter. The HuM had used him as a propagandist and fundraiser, and had even sent him to Africa and Europe.[9]However, such oratory skills of Masood Azhar and his standing as a religious scholar came handy and was a key factor in attracting and enlisting recruits from Indian Kashmir and the PoK. Ayesha Siddiqa attributes the recruitment successes of the JeM to failing agricultural system, absentee landlords who used to solve he financial problems of the poor, poor education and limited job opportunities in Punjab (Pakistan).[10]Siddiqa claimed to have seen open recruitment for JeM during her research visits to Bahawalpur. According to her, the fact that JeM could do so in an area, which also houses the Pakistan Army’s 31st Corps Command, points at an inevitable link between the two.[11]

Activities of the JeM were focused not just on Kashmir, but on mainland India. Not surprisingly, within two years of its establishment, it carried out the spectacular attack on the Indian parliament on 13 December 2001. Two months before, on 1 October, the JeM had carried out a suicide bombing of the Jammu and Kashmir legislative assembly building in Srinagar killing more than 30 persons.

The Assassination Bids

Azhar was arrested on 29 December 2001. According to Pakistan’s National Counter-Terrorism Authority, the JeM too was proscribed on 14 January 2002. Although the arrest and the ban came after pressure from the international community and India, in the wake of the 13 December 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament and the 9/11 attacks, Pakistan insisted that the ban had nothing to do with the Indian demand and was purely related to the sectarian activities of the JeM which included ‘suicide attacks on churches and missionary institutes in Islamabad, Murree and Taxila’[12]. Azhar was released after a three-member Review Board of the Lahore High Court ordered his release on 14 December 2002. The JeM, however, was re-banned in November 2003.

In December 2003, the JeM carried out a two assassination attempts on then President Parvez Musharraf. On the 14th, his car was targeted as it crossed the Jhanda Chichi bridge near the 10 corps headquarters in Rawalpindi. The bridge ‘had been wired with an estimated 250 kilograms of C4 explosives’[13]. On the 25th, ‘two suicide bombers tried to ram cars packed with explosives into the presidential convoy, not far from the venue of the first attack’. The 14December attack killed none, whereas 14 persons including the two suicide bombers were killed in the second attack. The attacks led to a massive overhaul of the President’s security arrangement. Additionally, the intelligence failure that had led to the attack cost director-general of military intelligence Major General Tariq Majeed his position. He was replaced with Musharraf’s military secretary Major General Nadeem Taj.

Suspicion fell on the al Qaeda, since few months back the group’s then deputy chief Ayman al- Zawahiri had called upon the Pakistani security forces to topple General Musharraf for “betraying Islam”. The investigations also pointed at the possible role of the Brigade 313 alliance consisting of five militant organisations including the JeM, Harkatul Jihad al-Islami, LeT, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and Harkatul Mujahideen al-Alami. Brigade 313 had come into being shortly after the US started its operations in Afghanistan in October 2001. The militant leaders had pledged to target key Pakistani leaders who, were ‘damaging the cause of jihad’ in order to ‘further the American agenda in Pakistan’. Subsequently, two suicide bombers responsible for the 25 December were identified as Mohammad Jamil, a 23-year-old JeM recruit from Poonch district of Kashmir and Hazir Sultan, a HuJI cadre Afghanistan.

These attacks led to a series of steps by the government against the JeM. On 26 December, Azhar’s younger brother and the JeM deputy chief, Mufti Abdul Rauf, was arrested from Rawalpindi. A manhunt was also launched for Azhar who reportedly had gone into hiding. Azhar was subsequently arrested and lodged in Bahawalpur Central jail, before being put under house arrest. Azhar wrote afterwards, “While I was lodged in Bahawalpur Central jail, the jail administration feared that my friends and companions may attack them. So I was shifted to Dera Gazi Khan.”[14] Subsequently, his own home was declared a sub-jail and he was put under house arrest.

This seemed to have minimal impact on the JeM’s operational ability. Between 2003 and 2008, it not only operated openly in parts of Pakistan, it conducted a series of high-profile attacks. In July 2004, Pakistani authorities arrested a JeM member wanted in connection with the 2002 abduction and murder of US journalist Daniel Pearl. In 2006, JeM claimed responsibility for a number of attacks, including the killing of several Indian police officials in Srinagar. JeM was also involved in the 2007 Red Mosque uprising in Islamabad. Masood Azhar, who had been released from house arrest and was openly preaching in mosques all over the country, went underground that year.

The fact that JeM was involved in the assassination attempts on Musharraf, the attack on the Indian parliament and killing of journalist Daniel Pearl was admitted by former chief of the ISI, Lt. Gen. Qazi, who was a cabinet minister in Musharraf’s government. He said in the Pakistani Senate on 6 March 2004, “We must not be afraid of admitting that the JeM was involved in the deaths of thousands of innocent Kashmiris, bombing the Indian Parliament, Daniel Pearl’s murder and attempts on President Musharraf’s life.”[15] Qazi, however, asserted that ISI had nothing to do with the extremist and sectarian outfits in Pakistan and there was no truth in the allegations that they were patronized by the establishment.

Remarriage of Convenience

In 2008, however, the estranged JeM started finding favours with the Pakistan military. In June that year, the outfit’s leadership was reportedly working to resolve its differences with other Pakistani extremist groups and began shifting its focus from Kashmir to Afghanistan in order to step up attacks against US and coalition forces. Over the next few years, the relationship was cemented. In return for the Pakistan military providing the JeM freedom to organise its activities in the country, the JeM begun expunging anti-Pakistani elements from the organisation. The 2008 Mumbai attacks in which the LeT was involved brought in lot of attention on the group and its sponsors within the Pakistan military. Indian intelligence agencies believe that the latter was in lookout for a group that would continue the LeT’s work in Kashmir. The JeM perfectly fitted the role. Ayesha Siddiqa notes, the outfit was “back in full force with offices in every neighborhood”[16].

It is this time that the JeM felt the need to expand its real estate and set up its permanent headquarters. A US Department of Defense document of November 2008 reveals the presence of a newly built madrassaon the outskirts of Bahawalpur city headed by a devotee of Maulana Masood Azhar identified only as Maulana Al-Hajii.[17] Locals told the US embassy officials that ‘these sites were primarily used for indoctrination and very limited military/terrorist tactic training. They claimed that following several months of indoctrination at these centres youth were generally sent on to more established training camps in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and then on to jihad either in FATA, NWFP, or as suicide bombers in settled areas.’[18] They also said that their repeated complain to the government regarding the rise of extremism in the area through these indoctrination centres have been ignored. Ayesha Siddiqa observes that without the tacit support from the military and the ISI, dismantling such centres would have been a simple police action.[19]

An Indian investigative report made a similar observation. “In 2009, just months after the Mumbai attacks of 26 November, 2008, Rauf arrived at a small government office in Bahawalpur to register the purchase of nine acres and one kanal of farmland off the Bahawalpur-Karachi highway. For a stated value of 1.5 million Pakistani rupees, a local, Ahmad Nayeem, sold the property to Rauf and his partner, Rashid Ahmed, on 23 March of that year.”[20] The Sunday Telegraph reported in 2009 that the facility even had a ‘fully-tiled swimming pool, stabling for over a dozen horses, an ornamental fountain and even swings and a slide for children’[21]. Both the JeM and the Pakistani officials maintained that the facility is simply a small farm to keep cattle. In the next few years, this property grew into a sprawling JeM facility on the outskirts of the city, which the organisation’s propaganda material says, has space for 12,000 students, sports facilities and prayer areas.

The public activity of the proscribed JeM increased noticeably. With the tacit approval of the military and the ISI, open meetings were organised in Dera Ismail Khan and Muzaffarabad among other places. One such public meeting for militants was organised in mid-January 2010 in Muzaffarabad by the militant alliance, the United Jihad Council (UJC) of which the JeM is a member. The meeting was chaired by, among others, former chief of the ISI, Lt Gen Hamid Gul. It was concluded with a call ‘for a reinvigorated jihad(holy war) until Kashmir was free of “Indian occupation”.’[22] In January 2014, Masood Azhar addressed supporters gathered in Muzaffarabad from an undisclosed location and said the time had come to resume jihad, or holy war, against India. A journalist from Reuterswho attended the gathering reported that a telephone was held next to a microphone which broadcast his comments to loudspeakers. JeM flags, inscribed with the word “jihad”, fluttered in and around the venue.[23] It appeared that while the continuing proscription of JeM and his health issues discouraged its chief from making public appearances, but it had no impact on the groups’ mobilisation activities.

It is also during this period that the JeM successfully sought funds within and abroad to build mosques and madrassas. ‘In 2010, a JeM-affiliated publication said the trust was paying pensions to the families of at least 850 jihadists killed or imprisoned in India, as well as in other countries.’[24] In addition, Pakistan’s government had issued legal permissions for JeM-related publications to print, and to solicit advertisements.

Rising Profile & Growing Clout

By 2016, the JeM was showing signs of growing too big even for its mentors. Following the attack on the Indian Air Force base in Pathankot, Azhar (under the pseudo name Saidi) wrote in the group’s online journal al Qalam warning the Pakistan government against cracking down on the group, as it may become ‘very dangerous’ for the country.[25] Azhar ridiculed Pakistan for being overtly India friendly. “…There is a lot of noise coming from India regarding us — arrest, kill, arrest, kill — and here our rulers are in anguish because, perhaps, we have disturbed their intimacy and friendship (because) they want that on the day of judgment, they should stand as friends of Modi and Vajpayee”[26], he wrote.

Explaining JeM’s stand vis a vis the Pakistani government, he wrote: “Our thinking regarding Pakistan has always been based on wishing it well and peace…not to save our life and skin but for the interests of Muslim Umma(nation) and in the interest of jihad. I am sorry that the rulers here (in Pakistan) have no respect for that. They (have) continued to be guided by those who are not our own — and they (rulers) continue to turn their own country into a heap of explosives and fire. Each one of them comes and puts their own country on fire and then they flee.”

This was a significant indicator of the JeM asserting its utility for the Pakistan state, going even to the extent of warning it against any policy shift. It carefully targeted Pakistan’s (civilian) government’s inclination to start a peace process with India. It is, however, possible that the statement had been issued at the military’s behest, who professes a similar anti-India world view.

The same situation prevails even today. There are reasons to believe that the deep state in Pakistan is unwilling to take steps to curb the activities of the JeM and other terrorist groups. Two recent instances are indicators of this trend. After India carried out air strike on the JeM camp in Balakot on 26 February, Pakistan’s foreign minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi admitted that Azhar is in his country. His statement, however, was quickly dismissed by the military spokesperson who feigned ignorance about Azhar’s whereabouts. “Jaish-e-Muhammed does not exist in Pakistan. It has been proscribed by the United Nations and Pakistan also”, Director General Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) Major General Asif Ghafoor told the CNN in an interview.[27] Similarly, following the 14 February 2019 suicide attack in Pulwama, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Interior announced that the Punjab government has taken control of a campus of the Jama-e-Masjid Subhanallah in Bahawalpur, along with the Madressatul Sabir— both parts of the complex belonging to the JeM.[28] But, just a day later, Bahawalpur deputy commissioner Shahzaib Saeed told a group of visiting journalists it was just a “routine seminary having no links with the Jaish-e-Mohammed… Some 600 students are studying here and none of them is associated with any banned organisation or involved in any terror activity”. Pakistan’s information and broadcasting minister Fawad Chaudhry joined him in denial. “This is a seminary, and India is doing propaganda that it is the JeM headquarters,” the minister said.[29]

Strategy to neutralize JeM

The suicide attack carried out at Pulwama by a JeM cadre on 14 February 2019 has brought renewed attention on the group and is serving as a raison d’etre for the call for declaring Masood Azhar a global terrorist. The group’s linkages with the Afghan Taliban and the al Qaeda, however, has been less talked about. At a time when Afghanistan is witnessing important developments on peace negotiations with prospects of future power sharing arrangement with the Taliban, such nexus cannot be overlooked. The JeM’s connections with Taliban/ al Qaeda would serve as a much-needed instrument of influence in the near as well as in the long-term for the deep state. Strengthening of the JeM in Kashmir is another wherewithal for calibrating violence that the military in Pakistan would like to exploit.

Some analysts in India believe that generational change within the JeM may bring about significant power equation transformations with its patrons. Such speculations have based themselves on the reports that Masood Azhar has serious health issues and may not survive for very long, giving rise to leadership contestations and even a split within the organization. Such assumptions are not completely unfounded. JeM’s establishment did undermine the HuM and its leadership. However, historically many terror organisations like the JeM have demonstrated a unique vitality that enables them to withstand losses of important leaders which include even their founders. That is the reason why eliminating terrorist leaders is not considered a full proof counter-terrorism strategy. The environment which sustains them must be curated, if not transformed. A strategy that imposes huge costs to the patrons of JeM is more important than neutralizing the outfit alone.

It is in this context that the strategy of the Pakistan military to switch between the two predominant terror groups, the JeM and the LeT, must be taken note of. When international attention focuses on one, usually following a terror attack, that group is kept at a low profile and the other one is propped up. What remains constant, however, is the symbolic official measures against the JeM and the LeT within Pakistan, directed mostly at managing international criticism. Pakistan counts on the support from China to keep the JeM safe and is unlikely to give up on this instrument of choice in near future. The JeM is deeply entrenched within Pakistan. Its primary source of strength is mostly within Pakistan and partly in Kashmir. The skewed civil military relationship and the collapse of the Pakistani state’s ability to effect socio-economic regeneration in Punjab and Sindh accentuates the problem. Thus, India’s actions targeting the JeM within Kashmir or through strikes on Pakistan would have only limited value. Pakistan needs to change its course and there is no other alternative than to building consistent pressure on it through an array of mechanisms.

End Notes

[1] S K Malik, ‘The Quranic Concept of War’, (New Delhi: Himalayan Books, 1986), p. 57.

[2] Praveen Swami, “Masood Azhar, in his own words”, Frontline, vol.18, issue. 21, 13-26 October 2001, https://frontline.thehindu.com/static/html/fl1821/18210190.htm. Accessed on 21 March 2019.

[3] Writers like Ayesha Siddiqa, however, indicate that JeM was established by Masood Azhar in 1994.

[4] Amir Mir, Talibanisation of Pakistan: From 9/11 to 26/11 and Beyond, (Pentagon Press, 2009), p.107.

[5] ibid, p.106.

[6] “15 years ago, US took note of JeM’s major terror training camp in Balakot”, Hindu, 26 February 2019, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/15-years-ago-us-took-note-of-jems-major-terror-training-camp-in-balakot/article26379168.ece. Accessed on 1 April 2019.

[7] Andy Worthington, “The Unknown Prisoners of Guantanamo (Part Two)”, Wikileaks, 31 May 2011, https://wikileaks.org/The-Unknown-Prisoners-of,101.html. Accessed on 1 April 2019.

[8] Raffaello Pantucci, “A Biography of Rashid Rauf: Al-Qa`ida’s British Operative”, CTC Sentinel, July 2012, vol. 5, issue 7, https://ctc.usma.edu/app/uploads/2012/07/CTCSentinel-Vol5Iss74.pdf. Accessed on 5 April 2019.

[9] Praveen Swami, “The Jaish-e-Mohammad’s fidayeen factory: How Masood Azhar set up his industry of terror in Kashmir”, Firstpost, 26 February 2019, https://www.firstpost.com/india/the-jaish-e-mohammads-fidayeen-factory-how-masood-azhar-set-up-his-industry-of-terror-in-kashmir-6129311.html. Accessed on 7 April 2019.

[10] Ayasha Siddiqa, Military Inc.: Inside Pakistan’s Military Economy, (London: Pluto Press, 2007).

[11] US State Department Cable, Bahawalpur: Growing Militant Recruitment in southern Punjab, 4 February 2009, Published in Wikileaks, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09ISLAMABAD237_a.html. Accessed on 7 April 2019.

[12] Amir Mir, Talibanisation of Pakistan. Op.cit. p. 110.

[13] Amir Mir, “After they failed to assassinate Musharraf”, Herald Dawn, 14 December 2017, https://herald.dawn.com/news/1153914. Accessed on 31 March 2019.

[14] Muzamil Jaleel, “Pakistan on dangerous road, God’s army won’t feel my absence: Jaish chief Masood Azhar goes online”, Indian Express, 14 January 2016, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/pakistan-on-dangerous-road-gods-army-wont-feel-my-absence-azhar-goes-online/. Accessed on 31 March 2019.

[15] B Muralidhar Reddy, “Jaish behind Parliament attack: ex-ISI chief”, Hindu, 7 March 2004, https://www.thehindu.com/2004/03/07/stories/2004030703320900.htm. Accessed on 31 March 219.

[16] ‘Bahawalpur: Growing Militant Recruitment in southern Punjab’, op.cit.

[17] “Extremist Recruitment on the rise in southern Punjab”, 13 November 2008, Wikileaks, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08LAHORE302_a.html. Accessed on 1 April 2019.

[18] Ibid.

[19] ‘Bahawalpur: Growing Militant Recruitment in southern Punjab’, op.cit.

[20] “Property records nail Pakistani lie on Jaish-e-Mohammed HQ in Bahawalpur, finds Firstpost investigation”, First Post,1 March 2019, https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/property-records-nail-pakistani-lie-on-jaish-e-mohammed-hq-in-bahawalpur-finds-firstpost-investigation-3598911.html. Accessed on 1 April 2019.

[21] Saeed Shah, “Al-Qaeda allies build huge Pakistan base”, The Telegraph, 13 September 2009, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/pakistan/6180118/Al-Qaeda-allies-build-huge-Pakistan-base.html. Accessed on 7 April 2019.

[22] Syed Shoaib Hassan, “Why Pakistan is ‘boosting Kashmir militants’”,BBC, 3 March 2010, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4416771.stm. Accessed on 2 April 2019.

[23] Sanjeev Miglani & Katherine Houreld, “Pakistan militant Maulana Masood Azhar resurfaces, ignites fears of attacks”, 18 February 2014, https://in.reuters.com/article/jaish-e-mohammad-masood-azhar-india-paki/pakistan-militant-maulana-masood-azhar-resurfaces-ignites-fears-of-attacks-idINDEEA1H01T20140218. Accessed on 2 April 2019.

[24] Praveen Swami, “With backing of ISI, Jaish-e-Muhammad rises like a phoenix in Pakistan”, Indian Express, 11 January 2016, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/with-backing-of-isi-jaish-e-muhammad-rises-like-a-phoenix-in-pakistan/. Accessed on 1 April 2019.

[25] “Action against Jaish-e-Mohammad will be dangerous for Pakistan, warns Masood Azhar”, Times of India, 15 June 2016, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Action-against-Jaish-e-Mohammad-will-be-dangerous-for-Pakistan-warns-Masood-Azhar/articleshow/50583986.cms. Accessed on 31 March 2019.

[26] Muzamil Jaleel, “Pakistan on dangerous road, God’s army won’t feel my absence”. Op.cit.

[27] “Jaish-e-Muhammed does not exist in Pakistan: Military spokesperson”, Economic Times, 6 March 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/pakistan-army-chief-to-brief-parliamentarians-on-hostile-situation-at-loc/articleshow/68654296.cms. Accessed on 1 April 2019.

[28] Sanaullah Khan, “Punjab govt takes ‘administrative control’ of Bahawalpur seminary”, Dawn, 22 February 2019, https://www.dawn.com/news/1465406. Accessed on 1 April 2019.

[29] “Property records nail Pakistani lie on Jaish-e-Mohammed HQ in Bahawalpur”, op.cit.

© Dr Bibhu Prasad Routray