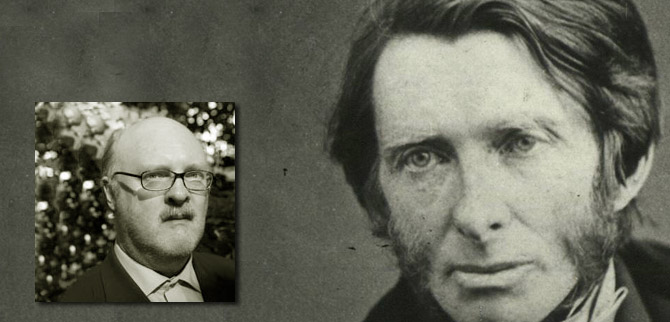

Why John Ruskin Still Matters by David Morgan

David Morgan looks at the work of the 19th century British art critic and social commentator John Ruskin to discover what he has to teach us today.

David Morgan has been a professional editor and journalist for over thirty years beginning his career on the subs desk of the Morning Star newspaper. He is editor of numerous historical publications under the Socialist History Society imprint. David’s interests and research include Turkey and the Kurds, literary figures like George Orwell, Edward Upward and William Morris, British anarchism, the 17th century English revolutionary era and the history of psychoanalysis. He has contributed towards many different publications and writes review articles, commentaries, opinion pieces, polemics and poetry.

“How deadly dull the world would have been twenty years ago but for Ruskin!”

This was William Morris writing in 1894 in his famous article, ‘How I Became a Socialist’, which appeared in the political journal, Justice. Here Morris pays tribute to John Ruskin as the most powerful critic of Victorian society and the main inspiration for his own work as an artist and political activist.

Morris had also read Marx, he worked alongside Marx’s political partner, Friedrich Engels and his daughter Eleanor Marx; historians such as E P Thompson and Ray Watkinson have seen William Morris as a pioneer English Marxist. It very pertinent that Morris himself should choose John Ruskin as his formative inspiration. Describing Ruskin as “my master”, Morris says, “It was through him that I learned to give form to my discontent, which I must say was not by any means vague. Apart from my desire to make beautiful things, the leading passion of my life has been and is hatred of modern civilization.”

By “hatred of modern civilisation” Morris means the injustices, suffering and conflict created by modern society in its relentless pursuit of progress and private wealth. In this respect, Ruskin famously sums up his own attitude to social ills when he states “there is no wealth but life”.

Morris of course saw himself as a socialist, even a revolutionary Communist, although the meaning of “Communist” in the 19th century differed greatly from its meaning after 1917; Morris associated it with the Paris Commune of 1871. Ruskin, by the way, had strongly opposed the Communards, but he was still able to inspire some of Britain’s foremost socialists. Ruskin was a great independent thinker who displayed tremendous courage; he was unafraid to espouse radical, even revolutionary, ideas, but he never defined himself as a socialist as such. It is without doubt not insignificant that Ruskin had ceased all public activities by the late 1880s, the decade when the modern socialist parties began to be formed and an organised independent labour movement emerged. Ruskin was to work closely with the Christian Socialists collaborating with them to provide education for workers and artisans when he taught art and drawing classes at the London Working Men’s College, enlisting Pre-Raphaelites such as Rossetti to teach at the college as well. Labels really matter very little; what actually counts is what people do: while not a card-carrying socialist, Ruskin was always keen to encourage the talents of individual workers by employing them and commissioning them to undertake creative work, such as painting.

Like Morris, many prominent people, artists, writers, social reformers, pioneers in different fields, many original thinkers, and political leaders, as various as Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi and Marcel Proust, have drawn valuable lessons from studying Ruskin’s work and following his example. Gandhi, for example, was to translate Ruskin’s “Unto This Last” into Gujarati retitling it “The Welfare of All” (Sarvodaya); in doing this, Gandhi declared that some of his “deepest convictions” had been learned from reading Ruskin and he went so far as to state that the encounter with Ruskin “transformed his life”. Many people less famous than Gandhi could express exactly the same sentiments.

Ethical socialism with which Ruskin is commonly associated in Britain was once a major influence in the Labour Party and Ruskin’s name was frequently cited by Labour pioneers as the public figure whose many writings helped shape their political outlook and opinions. When the journalist W T Stead questioned the first intake of Labour MPs on their influences many cited the works of Ruskin. “Unto This Last” was the book that was most often mentioned. “Ruskin seems to have been regarded by many who were active in the movement as a fellow socialist,” commented historian David Martin in a study of the early Labour Party from 1906-1914. Robert Blatchford, the editor of The Clarion newspaper, included Ruskin alongside Morris, H M Hyndman, Edward Carpenter, George Bernard Shaw and Annie Besant as leading British socialists. Ruskin was also included in a once influential study titled Great Democrats, published in 1934, a weighty tome that consisted of forty profiles of the pioneers of democracy, Chartists, Christian Socialists and early Fabians. In reality, Ruskin was far from being a “democrat” in the modern sense of the term at all and he had very little respect for Parliament denouncing the building itself as the “most effeminate and effectless heap of stones ever raised by man”; one suspects that Ruskin was not simply thinking of the style of the building alone.

Ruskin’s social and political influence declined considerably in the early 20th century under the cumulative impact of the assault on Victorian values waged by the likes of Lytton Strachey in books like Eminent Victorians and the harrowing experience of the catastrophe of world war which instilled a widespread feeling scepticism and hostility to heroes of all kinds. While Ruskin did not aspire to heroism, he did a cast himself in the role of teacher and opinion former and his general approach as a social critic came to seem old fashioned. His language had become somewhat archaic. Today, that is even more so. It is no longer easy to speak about ethical values or to espouse morality in today’s culture. We inhabit a culture where cynicism is the norm and where mention of things like “virtue” or “honour” or “joy” are belittled. Even the words are now hardly used so much have they been erased from public discourse. The prose of a Victorian like Ruskin can seem extremely remote even though the issues that concerned him, namely the environment, social justice, education, housing, poverty, the nature of work and the importance of cooperation are just as urgent now as they were two centuries ago.

Ruskin’s ideas live on, not just in Britain, but around the world where active Ruskin societies can be found as far afield as the US, India, Russia and Japan. As celebrations take place to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth, it is the perfect occasion to revisit his legacy and explore Ruskin’s abiding influences. So who exactly was John Ruskin? What did he stand for? And why are the ideas of this mid-Victorian writer not only still relevant today but becoming modern again?

He was born on 8th February 1819 and his life spanned the entire Victorian age. He died in 1900 but spent the last ten years confined to his home in Brantwood on Coniston Water, a virtual recluse sheltered from the world that had long become too hostile for him to endure and cared for by his relatives; late photographs show Ruskin as a frail old wreck of a man wearing a long, untidy beard resembling Shakespeare’s King Lear.

He had been a child prodigy writing competent poetry before he reached his teens. He was an only child born to extremely protective parents; his mother taught him at home, instructing him to read the Bible from end to end and memorise entire passages. His mother accompanied him to Oxford when he went to university and his father visited them at weekends. He never experienced poverty and had no need to work for a living. His only paid job was as Slade Professor at Oxford a post he held from 1869–1878 and again from 1883–1885; he finally resigned over the issue of vivisection which he strongly opposed.

Ruskin could have chosen to live a life of luxury and leisure on the generous allowance provided by his wine merchant father and a private income derived from the lucrative sherry business. It is admirable that he didn’t choose to squander his inheritance on self-indulgent trifles and excess but devoted millions of pounds to individual acts of charity, sponsoring countless good works, educational activities, public museums and financing causes such as housing for the poor all with the aim of improving the social conditions of his fellow citizens. His strong sense of duty and commitment to the community are values that should today be more widely emulated by the rich and powerful in our own society. He stated that he practised what he preached and he was widely revered as a good natured and “gentle man”. In public and in private he was the Good Samaritan, the good neighbour and the good citizen.

His singular vision was inspired by Biblical teaching but also by the splendours of the natural world he saw around him and all its living creatures. He was inspired in equal measure by the abundant beauties of nature in all its manifestations from the grandeur of the mountains to the intricacies of a flower and even a dried leaf attracted his attention because he was able to see beauty in its intricate form. The colours of nature were a source of inspiration. The blue scarf that he always wore became his trademark. Its natural colour was symbolic of the sea and the sky which he loved rather than an indication of political allegiance.

His consciousness of the world was essentially green and he has been claimed as a pioneer environmentalist or ecologist. He spoke in opposition to railway construction because he was aware of the destructiveness of development and that in interfering in the natural environment to make way for progress was to wreck a destruction that was permanent.

Ruskin has been described as Britain’s Goethe and like Goethe he combined many interests that are usually seen as quite distinct; typically those of the artist and the scientist. In an essay, “John Ruskin as a Victorian Goethe”, Elémire Zolla writes:

‘He was one of those people …who refuse to restrict themselves to one specialty, surrendering themselves to the corporate delirium that oppresses modern people, bound to a division of intellectual work that is an aspect of the linguistic confusion of Babel. The art critic won’t dare to look at the stones that nevertheless speak like the pigments of a painting, the metaphysician doesn’t dare descend to the art gallery to enlighten the judgement of those who contemplate works of art, or to the marketplace to judge the fairness of contracts. Ruskin challenged the taboo of specialties, of exclusive skill. He understood that the universal conditions of what is conceivable, the supreme intellectual principles, permit one to contemplate, act, and judge, and that whoever knows them has the right to bring order into the chaos in individual disciplines.’

Ruskin began his writing career as an art critic defending the work of Turner in Modern Painters, which is a work of five volumes, published over a 17 year period starting in 1843. But he was never solely interested in art. He was concerned with the circumstances surrounding how art was produced and especially the conditions of work of those who produced art. When he began to study architecture, Ruskin became preoccupied with whether the workers derived any satisfaction from the tasks they were compelled to carry out. He believed in human creativity and that those who undertook the work should be happy in doing it. It was an indictment of the society if workers were working under conditions of compulsion amounting to slavery. He chose the learn from history to embolden his critique of contemporary society and drew a stark contrast between what he believed were the more human-centred and integrated circumstances that the craftsmen of the Middle Ages had experienced comparing their situation unfavourably with the harsh, mechanical and repetitive conditions endured by workers in the industrialised factories. His interest of the medieval period was emphatically not driven by nostalgia.

This brief summary is to crudely simply Ruskin’s basic arguments and much more could be said, but the main point is that his critique of industrialised capitalism and the economics of the free market posed a great challenge to the fundamentals of how society was run and the prevailing orthodoxy. For this Ruskin incurred the wrath of the defenders of liberal capitalism and he was to be attacked mercilessly in the press.

Different strategies were adopted to undermine Ruskin and tarnish his reputation which persist to this day and can be found in historical studies of the Victorians. He is frequently defined merely as an ‘aesthete’ akin to Oscar Wilde, who was incidentally a great admirer of Ruskin. The portrayal of Ruskin in the film, Mr Turner, by British director Mike Leigh about the life of Turner includes a gross caricature of Ruskin as an effete aesthete which reflects the contemporary lampoons in the Victorian press. Alternatively, there is the tendency among commentators to dwell obsessively on Ruskin’s private life and especially his failed marriage to Effie Gray; much of the innuendo is largely based on threadbare evidence, pure speculation and derives from the whispering campaign that Gray’s supporters engaged in their attempt to destroy Ruskin’s reputation and by so doing elevate his former wife as the blameless victim. Nothing more need be said about this, apart from to state that it should not be used as a means of obscuring interest in Ruskin’s bold and original ideas or in undermining his courageous critique of social injustice. We have a lot that we can learn from Ruskin in how we run our society and how we treat each other as human beings and how we relate to the planet and all the other living creatures that inhabit it.

Ruskin’s philosophy of life is best summed up in his own simple but beautiful words: “I will not kill or hurt any living creature needlessly, nor destroy any beautiful thing, but will strive to save and comfort all gentle life, and guard and perfect all natural beauty upon the earth.”

© David Morgan