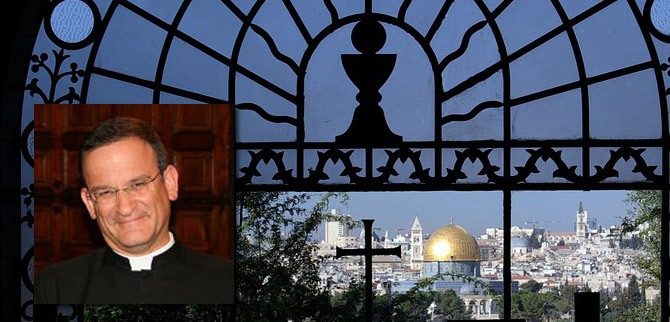

A personal reflection on dialogue with Muslims – an experience in Jerusalem

by Rev. Dr. David Mark Neuhaus SJ

Rev. Dr. David Mark Neuhaus SJ is a member of the Society of Jesus (Near East Province) and teaches Scripture at the Seminary of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem in Beit Jala, in the Religious Studies Department at Bethlehem University, at the Salesian Theological Institute in Jerusalem and at Yad Ben Zvi in Jerusalem.

He completed a BA, MA and PhD (Political Science) at Hebrew University, Jerusalem. He then completed pontifical degrees in theology and Scripture in Paris (Centre Sevres) and Rome (Pontifical Biblical Institute).

His publications include Justice and the Intifada: Palestinians and Israelis speak out (edited with Kathy Bergen and Ghassan Rubeiz), New York, Friendship Press, 1991; (in collaboration with Alain Marchadour), The Land that I will show you…Land, Bible and History has been published in French (2006), English (2007), Italian (2007), German (2011) and Korean (2018); and Writing from the Holy Land, has been published in French (2017) in English (2017) and Italian (2018).

He served from 2009 to 2017 as Latin Patriarchal Vicar for Hebrew Speaking Catholics in Israel and as coordinator of the Pastoral Among Migrants within the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem.

Abstract: Recent events in the Middle East and their resounding echoes throughout the world have sharpened antipathies as Islam has become identified in the minds of many with its most extremist practitioners. How might the view from Jerusalem challenge this perspective on relations with Muslims? In reflecting on dialogue with Muslims from a Christian point of view, the reflections in this article are based upon the the experience of deep friendships with Muslims in Jerusalem. The Holy City can be a unique place for a Christian engagement in dialogue with Muslims focused not only on the Quran as Muslim Scripture but also on the long centuries of history that have forged attitudes and relationships.

Abstract: Recent events in the Middle East and their resounding echoes throughout the world have sharpened antipathies as Islam has become identified in the minds of many with its most extremist practitioners. How might the view from Jerusalem challenge this perspective on relations with Muslims? In reflecting on dialogue with Muslims from a Christian point of view, the reflections in this article are based upon the the experience of deep friendships with Muslims in Jerusalem. The Holy City can be a unique place for a Christian engagement in dialogue with Muslims focused not only on the Quran as Muslim Scripture but also on the long centuries of history that have forged attitudes and relationships.

In 1965, paragraph 3 of Nostra aetate announced the dawning of a new age in the development of the attitude of the Catholic Church towards Muslims. The text of the conciliar document states with limpid clarity: “The Church regards with esteem also the Muslims”. The long centuries that had known too much suspicion, antipathy and even violence were now to give way to a new epoch in which Catholics and Muslims were called to recognize how much they had in common and to work together to build a more just and more humane world. Without obscuring the differences, particularly with regard to the identity of “Jesus as God”, the document called on one and all to “forget the past and to work sincerely for mutual understanding and to preserve as well as to promote together for the benefit of all mankind social justice and moral welfare, as well as peace and freedom”. From a discourse based upon apologetics and polemics, Catholics were called to develop a discourse based on encounter and collaboration with Muslims.

The Catholic Church’s dialogue with Muslims has developed parallel to the Church’s dialogue with Jews, rooted in paragraph 4 of the same conciliar document. However, in the post-Vatican II Church, dialogue with Muslims and dialogue with Jews have taken different paths. According to a dominant Western theological discourse, Christianity has a unique relationship with Judaism, unlike that with any other religion. Due to this uniqueness, the responsibility for dialogue with Jews was assumed by the office that promotes Christian unity in the Catholic Church, whereas responsibility for the dialogue with Muslims was assumed by the office that deals with dialogue with believers of other religions. Jews are sometimes shocked to discover that this separation of responsibilities implies that the Jewish-Christian divide is considered a division internal to Christianity and, consequently, that Judaism is not seen by Catholics as a religion totally separate from Christianity. This was made explicit by Pope John Paul II when he spoke to Jews in the synagogue in Rome in 1986, “The Church of Christ discovers her ”bond” with Judaism by ”searching into her own mystery.” The Jewish religion is not ”extrinsic” to us, but in a certain way is ”intrinsic” to our own religion. With Judaism, therefore, we have a relationship which we do not have with any other religion. You are our dearly beloved brothers, and in a certain way, it could be said that you are our elder brothers.”

The strict division of the two dialogues, that with Jews and that with Muslims, is of course a consequence of history, cultural affinities and the theological presuppositions engendered by them. First and foremost, contemporary Jewish-Christian dialogue has been forged within the context of European history, often attempting to replace an anti-Judaic or even anti-Jewish perspective[1] with a philo-Judaic and philo-Jewish one. The dual heritage of the Enlightenment, creating a Judeo-Christian culture, and the Holocaust, which sought to destroy that culture, have moulded European cultural attitudes with regard to the Jewish people and the theology that derived from this context. As a result of this history, many refer to a “common Judeo-Christian heritage”, founded in shared Scriptures, promoting a heightened awareness of Jesus’s Jewish identity and milieu, developing a shared ethical teaching, establishing a common understanding of dialogue and a common program of joint action (in which the struggle against anti-Semitism plays no small part). Muslims are often regarded as newcomers to this friendship if not considered complete outsiders.

This theological understanding is rooted, to some extent, in a Christian tradition which understood Judaism as the ultimate praeparatio evangelica[2]. However, the flowering of Catholic positive theologies of Judaism is the fruit of the twentieth century. Most significantly, these theologies reflect a Christian awakening to the tragic and sinister consequences of “a teaching of contempt” (see Jules Isaac) that characterized Christian discourse about Jews and Judaism through the centuries. Pope John Paul II, giving expression to the heritage of the Council, stressed over and over again that Jesus was a Jew, that Jews and Christians share common Scripture (defined as the Old Testament) and common values and that the roots of Christianity are in Judaism. Whereas this attitude to Jews and Judaism is evident in Catholic teaching today, it is striking that it hardly ever emerged from the shadows in the hundreds of years of Catholic teaching and preaching about Jews that focused on their presumed responsibility for the death of Christ, their supposed blindness when reading Scripture and their ostensible stiff-necked rejection of the preaching of the Church.

In today’s Catholic discourse, whereas dialogue with Jews is often proposed as an existential obligation for Christians seeking to understand themselves, dialogue with Muslims is commonly conceived of as grounded in utility, reflecting a practical and political necessity in a shared world. This necessity is understood to relate to two parallel contexts. One is the context of Christian minorities living in countries with a Muslim majority and the dialogue seeks to guarantee not only their religious and human rights as Christians but also their full and equal citizenship in the state and in society. The other context is that of growing Muslim minorities in countries with a Christian cultural heritage and the dialogue seeks to guarantee that Islamic faith and practice does not clash with Western ideas of democracy, equality and integration. Within the context of the dialogue on the integration of Muslims in Europe and North America, the historical experiences of the Jews, with successes, after the French Revolution, and dismal failures, culminating in the Shoah, should be a constant point of reference.

The Catholic view of the dialogue with Muslims often presupposes that, as compared to Christians and Jews, Christians and Muslims indeed also share a heritage based in Scripture but that this commonality is sharply curtailed by a Quranic text that remains foreign to Christians. Whereas Jews and Christians might be enriched by reading together shared texts (in what Christians call “the Old Testament”), Muslims have their own Scripture and make reference constantly to a prophet unrecognized by Christian tradition, Muhammad. It is striking that Nostra aetate mentions neither the Quran nor Muhammad, the two fundamental defining features of Islam and the life of Muslims.[3]

For those located at the Church’s centre in Europe and North America, while Christians and Jews are perceived to share a European rooted culture, Christians and Muslims are felt to live in essentially differing cultural worlds. This difference, is of course, underlined by fears for security, media images of militant Islam and the challenges of integrating Muslim minorities. Theologically one might complete the picture. Whereas Judaism, assimilated to the religion of the Old Testament Israelites, is seen as “preparation for the Gospel”, Islam is condemned as “deviation from the Gospel”. Whereas “Judaism”, with its Old Testament patriarchs, kings and prophets opened the way for Christ’s coming; Islam, with its “false” prophet and “false” holy Book deviated from the fully revealed truth in Christ. Judaism is seen as the trunk upon which Christ and his first Jewish disciples sprouted and upon which the Gentiles who were converted to faith in Him in ever increasing numbers were grafted. At least since the Shoah, and more especially since Vatican II, Catholics celebrate that Jesus, his Mother, his disciples and his ancestors were all Jewish. Yet, Mohammed, Islam’s prophet, despite having come into contact with Christians and their claims about Jesus’s divinity, despite venerating his Mother and even referring to Jesus as the Word of God, constructed a religion which ultimately denies Jesus’s divinity and consistently refuses the Good News of the Church.

To all intents and purposes, Islam and Muslims are not perceived to be in the same inter-religious playing field as Judaism and Jews. Recent events in the Middle East and their resounding echoes throughout the world have sharpened antipathies as Islam has become identified in the minds of many with its most extremist practitioners. Some Christians are particularly concerned with what they identify as the “persecution” of Christians by Muslims in parts of the world where Christians live as minorities among Muslims. Some Catholics, congratulating themselves on present day Catholic dialogic openness, intellectualism and pacifism, frown on an Islam characterized (or caricaturized) as intolerant, violent and even genocidal. The ongoing skirmishes between the powers that be in this world and the popular image of a supposedly wide spread Islamic fundamentalism and extremism severely restrain enthusiasm for dialogue with Muslims and limit hope for its fruits.

Friendship in Jerusalem: An experience of dialogue

Friendship in Jerusalem: An experience of dialogue

How does the view from Jerusalem challenge the European perspective on relations with Muslims? Contemporary historiography is more aware than ever that the perspective of the one writing history is largely responsible for the way in which history is written. This is largely true for theology too. In reflecting on dialogue with Muslims from a Christian point of view, I need to state at the outset that my intuitions and thoughts have been forged in the experience of deep friendships with Muslims in Jerusalem… with Oussama, Yahya, Muhammad and others… What is at the root of these reflections are experiences of dialogue with Muslim friends in Jerusalem.[4] Jerusalem is a unique place for a Christian engagement in dialogue both with Muslims and with Jews and might offer a different perspective due to a number of reasons:

– The first and most obvious fact is that in Jerusalem Christians constitute a small flock, an often politically and socially insignificant minority. Historically divided among themselves, culturally predominantly Palestinian Arab, politically marginalised in the city, and preoccupied with a steady emigration, Christians are struggling for their survival as Christians (and as Palestinians and Arabs too).

– Christians are faced with two majorities in the Holy City. On the one hand, the politically dominant Jewish majority controls the city with an iron hand, promoting a unique identification of Jerusalem with Jewish identity and history. On the other hand, the majority of Christians are part of an Arab Islamic socio-political and cultural world having increasing difficulty accepting its own cultural and confessional diversity and in which the muscular imposition of Islamic religious, social, cultural and political discourse and mores is marginalizing non-Muslims.

– Indigenous Christians in Jerusalem are often ignored by the steady stream of foreign Christian pilgrims, visitors and even by many long term Christian expatriate residents. For many of these foreign Christians, the Church in Jerusalem is synonymous with those structures of stone which shelter holy sites and few encounter the Church of Christ made up of her living stones, the Christian witnesses who have constituted the Church of Jerusalem since her birth until the present day. For the past fourteen centuries, these Christians have lived and had their being within a world defined by Muslim Arab civilization.

An encounter with the Quran

Shortly after my arrival in Jerusalem as an adolescent, I embarked on another journey of discovery that took me into the world of another text – the Quran. Committed to learning Arabic, I asked my close Muslim friend, Oussama, to read the Quranic text with me each week. There is no doubt that the medium of friendship opened the Quran for me in a way that academic study cannot do. Hearing Oussama’s interpretations of what we read and feeling free to resonate with his readings or challenge them deepened our friendship. We would meet once a week and I would struggle with the letters until they became familiar and I slowly pieced together meaning from the words. This exercise continued for years, first with Oussama and then with Yahya; both friends, teachers and partners in an ongoing dialogue.

A fundamental experience for many Catholics committed to the dialogue with Jews is the dawning recognition of the Scriptural heritage that Jews and Christians share in the Old Testament. In reading the Quran within the context of the deepening of a friendly relationship, it struck me immediately that the text of the Quran is not a stranger to the library constituted by the Scriptures of Israel and those penned by the disciples of Jesus. The ancient Arabic poetry, its vocabulary and rhythm, evoke the Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek of the Scriptures held sacred by Jews and Christians. Pope Benedict XVI pointed this out in an interview on the airplane that took him to the Holy Land in 2009: “Islam was also born in an environment where Judaism and various branches of Christianity, Judeo-Christianity, Antiochian-Byzantine-Christianity were present, and all these circumstances are reflected in the tradition of the Quran. In this way, we have much in common from our origins, in the faith in the one God. For that, it is important on one hand to maintain dialogue with the two parts — with the Jews and with Islam — and as well a trilateral dialogue” (May 8, 2009). The common heritage is not only evident in the shared narratives about the great figures in the Old Testament and the New, but also in the identification of a common language to envision God, humanity and their relationship. Whatever the significant theological differences might be in how the Talmud, the New Testament and the Quran reinterpret the Scriptures of ancient Israel, much of the vocabulary, syntax and rhyme is part of a common heritage that Jews, Christians and Muslims share.

My own encounter with the Quran in the meetings with Oussama and Yahya opened up perspectives in my reading of the Biblical text that were refreshing and sometimes even liberating. In its terse and yet poetic use of the Arabic language, The Quran conceded a greater depth to certain well-known figures that they had not had before when I read the Bible as a Christian. Some of their humanity and struggle emerged with greater clarity. I understood better the figure of Satan (named Iblis) after meditating the Quranic text that describes him as being “not among those who bow down” (Surat al-A’araf, 7:11). It is not to God that Iblis refused to bow down but rather to God’s creature, Adam, proudly held up by God as the crown of creation but rejected by Iblis who haughtily proclaimed: “I am better than him, You have created me from fire whilst you created him from clay” (Surat al-A’araf, 7:12). It was an eye-opener to encounter the Quran’s Noah, poignantly experiencing the tragedy of losing one of his own sons in the floodwaters, a son who refused to heed the call of his father: “and he was one of those who drowned” (Surat Hud, 11:43).

In our reading sessions, Yahya introduced me to the text in the Quran that is described as being “the most beautiful of stories” (Surat Yusuf, 12:3), the chapter called Yusuf, corresponding to Genesis’s dramatic story of Joseph son of Jacob. I had often been troubled by the harsh portrayal of Potiphar’s wife in Genesis, seemingly driven by lust and callously willing to destroy her object of lust when he did not submit to her advances. It was liberating to encounter Potiphar’s wife in the Quran (named in Islamic tradition Zulaykha), inviting her neighbours to gaze upon Joseph’s beauty so that they might understand how she had lost her equilibrium. The women, so distracted by Joseph’s beauty, cut their hands with the knives they had been handed to use at the banquet they were served in her house as they exclaimed: “God be praised! This is no human being. This is naught but a noble angel” (Surat Yusuf, 12:31). Rather than a story of lust, the Quran tells a story of human love and desire, complicated by issues of trust and ties of fidelity. The story is indeed most beautiful because of its resonances with the complexity of human experience.

Over time, the opening verses of the Quran have become a part of my prayer, poetically echoing the Psalms: “In the name of God, merciful and compassionate, praise be to God, Lord of the worlds, merciful and compassionate, Sovereign of the day of judgment…” Likewise, the last chapter of the Quran resounds in my spirit: “Say: I seek refuge with the Lord of humankind, the Sovereign of humankind, the God of humankind, from the evil of the devious whisperer, who whispers into the hearts of humankind, of unclean spirits and humans”. The medium of friendship with Oussama and Yahya opened the text not only to my understanding but also to my spirit. Without their friendship and their testimony to the good life lived by them as faithful Muslims, the text would have remained closed, foreign and unknown.

A joint history written in blood

A joint history written in blood

One day, I had to cancel my Quran lesson with Oussama because I had been invited to the celebration of the Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary, which falls each year on October 7. “What does that feast signify?” asked Oussama. Of course, I had no difficulty explaining to Oussama the beauty of the rosary prayer as he himself would often pray with a Muslim masbaha (stringed beads very similar to the rosary), reciting the ninety-nine names of God. However, how could I explain to him that the date of the feast commemorated the victory won in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, miraculously “saving” Europe from the Muslim hordes that threatened its gates? Even more complex was the fact that these supposed hordes, defeated by the Christians, were none other than the Ottoman Turks, who had provided refuge for Jews fleeing the Catholic Inquisition in Spain and Portugal. In fact, as a pupil in the Jewish school I attended in my youth, I had learnt that the Jews in the Ottoman Empire had found not only refuge but also an Islamic milieu in which they could develop and prosper, in a fashion not always true of the Christian milieu in Europe. This was only one of the many times that my conversations with Oussama and Yahya turned to the shared history of Christians and Muslims.

Jerusalem conserves so many sacred stones, almost all of them soaked in blood. Jerusalem through the centuries has too often been a battleground where religion has justified war, violence and hatred. A religiously inspired imagination has led Muslims, Jews and Christians in different periods to lay claim to a monopoly of power in Jerusalem whereas the ongoing reality of Muslim, Jewish and Christian presence in Jerusalem challenges the religious imagination to come to terms with the religious “other”. Walking through the streets of Jerusalem, visiting the Holy Places that still stand and the ruins venerated where others once stood, provides a rich panorama for a metanoia oriented dialogue regarding the respective histories of Christians, Muslims and Jews. The Greek metanoia, the Arabic tawba and the Hebrew teshuva all refer to a basic spiritual intuition that as humans we sin, that we are in deep need of forgiveness of God and neighbour and that we must turn back again and again toward God and neighbour with hearts full of contrition, asking pardon.

Self-righteous Christians, who might point to Muslim political excesses, have much to learn from such a walk about in Jerusalem, listening to what the ruins (archaeological and human) left by centuries of Byzantine, Crusader and British rule, suggest about Christian ambitions to rule the Holy Land. Self-righteous Muslims have much to learn too from close attention to the ruins left by the sometime disastrous policies of Fatimid, Mameluke and Ottoman rulers. The present socio-political reality of Jerusalem has created and continues to create ruins as a dominant Jewish majority has not proved itself any less oppressive than some of its Christian and Muslim predecessors. Jerusalem should elicit a spirit of humility and profound contriteness of heart in all who have sought to dominate her.

Dialogue with Muslims in Jerusalem reminds Christians not only of a distant past when Christians as Crusaders waged war for Jerusalem, slaughtering not only Muslims but Jews and non-Latin Christians as well, but also of a more recent past when colonialism legitimated itself under the guise of the protection of “holy places” and Christian missionary activity. Dialogue with Jews in Jerusalem reminds Christians not only of a distant past when the adoption of Christianity as an official religion made the life of Jews increasingly unbearable but also of a more recent past when European persecution of Jews gave birth to the idea that Jews needed a refuge far from Europe, the ideology of Zionism and the dream of a “Jewish national homeland in Palestine”. Yet, let us not forget, dialogue with local Christians reminds us that life as a minority under a double majority, Jewish and Muslim Arab, can be challenging to say the least.

However, Jerusalem, as city of origins, can also teach that despite the centuries of conflict, the three religious traditions rooted in Jerusalem have developed in close relationship with each other. Not only do all three religious traditions emerge from roots in the Scriptures of ancient Israel, but also throughout the centuries, their respective traditions developed in response to, in reaction to or in contradiction of the traditions of the religious others. Jerusalem is a wonderful laboratory where we can experience the inter-relatedness of these three religious traditions. Jerusalem, herself, has been sacralised in similar ways by each community, each one chanting her praises, although only rarely in harmony.

The extremism, violence and rejection of some Muslims today might be understood against the backdrop of the extremism, violence and rejection of some of our own Christian antecedents. In addition, the ongoing festering of the wound left in Palestine by the creation of the State of Israel in 1948 and its expansion in 1967 have led to much despair and anger among Muslims. Even today, the manipulation of Christian vocabulary and thought by some Christians in order to justify occupation and discrimination in Israel/Palestine serves to perpetuate a situation of ongoing injustice that deeply troubles the Muslim world, the tragic fate of the Palestinian people. This is particularly evident when Christians, calling themselves “evangelical” and being called by others “fundamentalist” draw on Biblical texts to legitimate these same practices of occupation and discrimination. Whatever political options might be espoused, dialogue with our Muslim brothers and sisters should make us sensitive to the pain inflicted in history. The challenge evoked by a shared history, soaked in blood, is to strive to understand one another in the present in order to plot out a future that promises a respectful and responsible engagement with diversity rather than attempts to suppress it.

Complex cultural affinities

Complex cultural affinities

One evening, Yahya called to ask me to accompany him to a concert being offered in one of East Jerusalem’s cultural centres. The evening was a celebration of three great twentieth century Arab divas, Lebanon’s Feirouz and Egypt’s Umm Kalthoum and Leila Mourad. It was a beautiful evening where the three talented, young Palestinian singers were often joined by the audience in belting out the songs as the whole audience knew much of the repertoire by heart. It was only later, researching more about who these well-known singers were, that I discovered that Feirouz was a Christian, Umm Kalthoum a Muslim and Leila Mourad a Jew.

Jewish-Christian dialogue in the West is intimately linked to what has come to be known as the “Judeo-Christian” heritage. This heritage is now clearly perceived by both Christian and Jewish Europeans and North Americans, who share language and thought, providing a rich backdrop for the development of dialogue. Popes John Paul II, Benedict XVI and Francis have cited the writings of Jewish thinkers like Emmanuel Levinas, Martin Buber, Franz Rosenzweig and Abraham Joshua Heschel in order to underline this shared heritage. What we should not forget though is that this cultural affinity between Western Jews and Christians emerged from a long history of life together, where too often both Jews and Christians focused on what separated Jews and Christians rather than on what they shared. Formulating a supposed “Judeo-Christian heritage” as a foundation for dialogue is very recent, rooted in the critique of tradition and championing of reason in the Aufklärung (Enlightenment) and in the values of democracy, equality and fraternity proclaimed by the French Revolution. The Western perceived affinity between Jews and Christians is more fragile than many Christians want to believe and for many Jews today it went up in smoke in the gas ovens of Auschwitz and Treblinka.

Some years ago, when I was a student of theology in Paris, in a conversation with emeritus French Chief Rabbi René-Samuel Sirat, he commented that the contemporary test for the supposed Western culture of dialogue was no longer in the face-à-face with the Jews, but rather in the integration of Muslims in Europe. Would Muslims be allowed to be fully fledged Europeans? The historical experience of the Jews in Europe stands as a warning beacon as Europe deals with the integration of her Muslim minorities.

In these reflections from Jerusalem, I am not suggesting a priori that there is some kind of Middle Eastern or Arab model for dialogue which is fundamentally different from the European model. Inter-religious dialogue as a project clearly emerges from a specifically Western philosophical and cultural background and it is not yet evident that this culture of dialogue has rooted itself in Middle Eastern soil, especially in the light of the aftermath of the “Arab spring”. However, perceptions about what people of different religions share culturally or where they differ do not constitute universal truths and should not be taken for granted in our theological presuppositions. Jews and Christians who have lived for centuries side by side within one linguistic, cultural and socio-political milieu might indeed have developed a language and a perspective on the world that is largely shared despite their differing religious affiliation, however this can be equally true for Muslims and Christians (as well as Jews) who have side by side for centuries in non-Western countries where Islam has been the dominant religion.

Many Jerusalemite Christians share a cultural world with Muslim Arabs, “an Islamo-Christian heritage”, which facilitates a certain type of dialogue, especially one which fosters collaboration on joint social, cultural and political projects. I might add that this cultural world is a world in which Jews from the Arab world are not strangers. This kind of heritage blossoms not so much in theology or spirituality but rather in the world of music, cinematography and literature. Among the profound “inter-religious” experiences in Jerusalem today one can count listening to Umm Kalthoum, Feirouz or Leila Mourad, reading the works of poets and authors like Egyptian Muslim Ala al-Aswani, Lebanese Christian Amin Maalouf, Palestinian Arab citizen of Israel Christian Anton Shamas and Israeli of Iraqi origin Jew Shimon Balas or viewing the films of Egypt’s Christian Yousef Shahin and Lebanese Christian Nadine Labaki, who evoke the shared cultural heritage of the Mediterranean confessional communities. The Arab heritage shared by Muslims and Christians (and Jews too) is the rich background upon which an inter-religious dialogue develops.[5]

Furthermore, it is particularly striking in Jerusalem that for some Jews the “Judeo-Christian heritage” is no more important than the “Judeo-Muslim heritage”. Listening to certain Jews reflect on Muslims, a very different understanding of cultural affinities could develop. How many times have I heard from Jewish friends that: Jews have been protected under Islam (Spain and Turkey being the two prime examples) whereas they have been persecuted under Christendom; that Muslim dietary laws make them culturally closer to Jews (whereas Christians feed on pigs); that Muslim observance of the law, fasting, regulated prayers, charity made them religiously closer to Jews (whereas Christians worshipping idols are not truly monotheists). Jews can point out that Sa’ad ad’Din al-Fayyoumi (Saadyah Gaon) Musa bin Maimoun (Rambam-Maimonides) and the great Jewish Arab grammarians of the Middle Ages are still among the greatest Jewish authorities.

Inter-religious dialogue can be seen as a Western project that dictates a hierarchy of relationships in which the Jewish-Christian bond is primordial. However, it should be admitted that when one is situated outside of the European experience, perspectives might be different, allowing for the development of other relationships that serve too to bind humanity together. In Jerusalem, this perspective is severely impeded by the political reality of conflict. Muslim partners in dialogue often demand solidarity in the struggle for peace and justice for the Palestinians and for the Middle East and see any contact with Jews as unbearable “normalization”. Jewish partners in dialogue often demand support for the State of Israel as an expression of their national resurrection after the Shoah. I would like to point out the unfortunate effect of this political strife on the ability to think out the issue of Catholic dialogue with Jews and Muslims. Our attempts to sort out our relationship with those who are closest (historically, culturally, theologically) to us, Jews and Muslims, is impeded by the fact that going out to meet Muslims often precludes meeting Jews and going out to meet Jews often excludes meeting Muslims.

However, in Jerusalem, a city torn by this strife, an integrated reflection on dialogue might indeed be possible. Not in fleeing from the conflict but in immersing ourselves in the elusive ordinary encounters with Jerusalem’s Jews and Muslims and Christians, there is, I think, great potential for uncovering different perspectives on the project of inter-religious dialogue. I speak here of the real city of Jerusalem, not a metaphysical city of spiritual origins or an eschatological city of Christian finality, but a city which embodies the challenges of engagement with the other. Jerusalem is a city that seems to prevent dialogue – divided by real and imaginary walls, where her residents avoid each other. The Holy City is bleeding, torn and infected with the least holy of diseases, fanaticism, intolerance and hatred. Its uniqueness, I would suggest though, is in its brokenness. It is in fully facing this brokenness that Muslims, Jews and Christians can turn their eyes to heaven to implore the God they all recognize as Creator to renew the face of the earth and draw together all of these, His children.

Towards a future dialogue

My experience of dialogue with Muslims in Jerusalem is a personal one, lived in the context of individual encounters. With it is born the conviction that we have much to learn from the experience of dialogue with Muslims – about ourselves as Christians, about Muslims and about the God we all seek. The promise of expanding our horizons within this dialogue parallels how Christian horizons have already been expanded in the ongoing dialogue with Jews. I am painfully aware that my reflections are being formulated at a time when my Christian brothers and sisters in Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Pakistan and elsewhere in the Arab and non-Arab Muslim world are experiencing a very different face of Islam. In no way do I seek to minimize their loss, their suffering or their cry for justice. Christians who live in countries with a Muslim majority and have suffered at the hands of indifferent Muslim majorities and/or Muslim extremists have every right and perhaps even the duty to bear a very different witness. However, as Christians, we must remember that our own history, especially where we have been seduced by power and have dominated non-Christian minorities, frighteningly echoes much of what is happening in these countries today.

A renewed theology of inter-religious dialogue is one of the fruits of Vatican II. Dialogue with Jews and Muslims in Jerusalem reminds us that this theological perspective on relationship with the religious “other” was not always the Church’s view. Although, in the light of the Shoah, Christians are increasingly conscious of the anti-Jewish bias, known as “the teaching of contempt”, only very few remember that this contempt was extended to Muslims and Islam. Only a few decades ago the prayer for the conversion of “perfidious Jews” and “heretical Turks” was uttered in the same breath. Furthermore, when Islam was tackled by medieval Christian thinkers, it was often reduced to a new, powerful form of heretical Christianity mixed with Talmudic Judaism. The Talmud and the Quran were paired as sources of error (cf. the writings of Petrus Alfonsi, the Cluniac Corpus Toletanum, Ricoldus de Montecrucis and others). There is still much to do to replace “the teaching of contempt” about Islam, founded on apologetics and polemics, with a relationship with Muslims established on encounter in a shared world.

Engagement in dialogue in Jerusalem tends to raise questions about the Western theological way of presenting the Christian relationship with Jews and Muslims. Lived Judaism and lived Islam, the texts and hermeneutical traditions of Talmud and Quran, are among the real challenges in the dialogue with Jews and Muslims. In fact, Rabbinic Judaism and Islam present very similar challenges to Christianity. Both religions developed, thrived and spread in a world which had been exposed to the message of Jesus Christ. Both religions developed their own apologetics in the face of Christianity and polemics against Christian faith. The Christian tendency to reduce Judaism to praeparatio evangelica (thus ignoring the foundation of Rabbinic Judaism in Rabbinic literature, canonized in the Talmud) and Islam to deviatio ab Evangelio (thus ignoring the content of the Quran and its shared vocabulary, syntax and rhyme) obscures the need to confront the faith realities that contemporary Judaism and Islam constitute for Jews and Muslims, sharing a world with Christians. Jerusalem might indeed constitute a laboratory in which dialogue can truly confront the living reality of the religious other.

[1] Anti-Judaism is the antipathy towards the Jewish religion, based upon theological arguments. Anti-Jewish sentiment, commonly known as anti-Semitism, is the antipathy towards Jews, based upon supposedly historical, social or political arguments.

[2] The name of an apologetic work of Church Father and historian, Eusebius of Caesarea, Praeparatio Evangelica, in which he shows how the best of Greek philosophy is rooted in the ideas of the Old Testament prophets, whose thought prepared for the coming of Christ.

[3] Some Jews have suggested that this state of affairs characterizes Judaism too as contemporary Judaism is not defined by the Old Testament but rather by the Talmud and its great teachers, largely foreign to Christians (cf. Jacob Neusner, Adin Steinsaltz and others). Parallel to its discourse on Islam, Nostra aetate makes no mention of the Talmud and its Rabbis, who are definitive for Jewish life and practice today.

[4] Here I echo the profound insights of the Dutch Jesuit, who lived much of his life in Egypt, Christian van Nispen tot Sevenaer, whose little masterpiece “Chrétiens et Musulmans: Frères devant Dieu?” (Paris, Les Editions de l’Atelier, 2004) has inspired me over the years.

[5] In conceiving of non-Western cultural contexts in which inter-religious dialogue develops, the experience of European Christians engaged in dialogue with Ashkenazi Jews (Jews from Europe) is clearly only one possibility. The danger is that it be presented as the model to which all other dialogues must conform, thus becoming a kind of hegemonic ideology.

© Rev. David Neuhaus SJ

Profile of Rev. Dr. David Mark Neuhaus SJ

Born in Johannesburg, South Africa.

1979 Completed high school matriculation at King David High School.

1980 Completed preparatory studies, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

1983 Completed B.A. cum laude, Psychology and Political Science, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

1985 Completed M.A. cum laude, Political Science, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

1987 Completed M.A. thesis: “Politics and Islam in Israel, 1948-1987” (awarded the Michael Landau Prize for Research in the Social Sciences), Hebrew University.

1991 Completed PhD: “Between Quiescence and Arousal: The Political Functions of Religion: A Study of the Arab Minority in Israel 1948-1990,” Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

1991-1992 Teaching post in the Political Science Department, Boston College, USA.

1992 Entered the Society of Jesus (Jesuits).

1994-1995 Teaching post at the Holy Family College, Cairo, Egypt.

1998 Completed B.A. cum laude in Theology, Centre Sèvres Institut Supérieur de Théologie et Philosophie, Paris, France.

2000 Completed Pontifical License in Biblical Exegesis magna cum laude, Pontifical Biblical Institute, Rome, Italy.

2000 Ordained Roman Catholic priest.

2000 – Lecturer in Sacred Scripture, Judaism and Hebrew at Seminary of the Latin Catholic Patriarchate of Jerusalem, Beit Jala.

2001- Lecturer in Sacred Scripture and Judaism at Bethlehem University.

2001- Lecturer in Sacred Scripture, Biblical Theology and Judaism at the Salesian Theologate at Ratisbonne, Jerusalem.

2009-2017 Patriarchal Vicar for the Hebrew-speaking Catholics in Israel in the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Member of the Assembly of Catholic Ordinaries in the Holy Land and Latin Bishops’ Conference for the Arab Regions.

2011-2017 Coordinator of the Pastoral among Migrants in Israel in the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem

Publications: David Mark Neuhaus

1. (English) “False prophecy in a Promised Land,” Al-Fajr, 17.4.1988.

also published in Peace Office Newsletter, Vol. 18, no. 6 (Nov-Dec 1988), 9-12.

2. (English) “Jewish Conversion to the Catholic Church,” Pastoral Psychology, 37 (1988), 38-52.

3. “When non-violence is a crime,” Or Chadash, November 1988, 8-9.

4. “Prison mythology,” The Other Israel, no. 35 (Jan-Feb 1989), 11.

5. (English) Justice and the Intifada: Palestinians and Israelis Speak Out (eds. Kathy Bergen, Ghassan Rubeiz and David Neuhaus), New York: Friendship Press, 1991.

Translated into Dutch in two volumes:

Vitale Vrouwen: Israelische en Palestijnse Vrouwen over Gerechtigheid en Intifada, Den Haag: Kok Kampen, 1992.

Haviken en Duiven in en om Israel: Gerechtigheid en Intifada, Den Haag, Kok Kampen, 1993.

6. (Arabic) “Bayn al-sukūn wa-al-sahwa: bahth fi al-’aqaliyya al-‘arabiyya fi dawlat ’isra’īl 1948-1990 (Between quiescence and arousal: A study of the Arab minority in the State of Israel 1948-1990)”, Al-Liqa’, 8/4 (1993), 141-148

7. (German) Kritische Solidarität: Einige Uberlegungen zur Rolle privlegierter Christinnen und Christen im Kampf der Enteigneten, Trier: Aphorisma Kulturverein, 1995.

8. (French) “L’idéologie judéo-chrétienne et le dialogue juifs-chrétien,” Recherches de Science Religieuse 85/2 (1997) 249-276.

(Arabic) Al-Liqa’, 13/1-2 (1998), 193-231.

(Italian) “L’ideologia ebraico-cristiana e il dialogo ebrei-cristiani. Storia e teologia” at http://www.santamelania.it/

(Dutch) “Bijdragen vanuit het Midden-Oosten aan de dialoog tussen joden en christen,” in Christenen van het Midden Oosten na 2000 jaar, ed. L. van Leijsen, J. Kraemer and J. Verdonk, Den Haag, Kok Kampen, 2000, 99-107.

9. (German) “Wie man weiterkommt: Einige Mythen des gegenwartigen Dialogs unter Juden, Christen und Muslimen zerlegt,” in Offene Fragen im Dialog (eds. Jens Haupt und Rainer Zimmer-Winkel), Hofgeismar, Vortrage, 1998, 28-44.

10. (French) “Pour l’amour de la Torah : R. Johanan ben Zakkaï et l’origine du judaïsme rabbinique,” Le milieu du Nouveau Testament : Diversité du judaïsme et des communautés chrétiennes au premier siècle, Paris, Médiasèvres, 1998, 239-252.

11. (English and French simultaneously) “Letter to a future generation,” in Letters to a future generation (eds. Frederico Mayer and Roger Pol-Droit), Paris, UNESCO, 1999, 121-122.

12. (Arabic) “Ba‘d al-ta’amulat hawl ziyāratika ’ayuha al-’ab al-’aqdas (Some reflections on your visit, Holy Father),” Al-Liqa’, 1-2/15 (2000), 208-219.

13. (English) “Jewish-Catholic Dialogue in Jerusalem: Crying out for Context,” In all Things, Nov. 2000, 10-15.

(Italian) “Il dialogo ebraico-cristiano a Gerusalemme” at http://www.santamelania.it/

14. (English) “Tisha BeAv as seen from the Mount of Olives,” Occupational Hazard.org, in Voices and Dialogue, 8.5.2001

(http://occupationalhazard.org/article.php?IDD=401)

15. (English) “Kehilla, Church and Jewish People,” Mishkan, 36 (2002), 78-86.

16. (English) Joseph in the Three Monotheistic Faiths with Ibrahim Abu Salem and Rabbi Jeremy Milgrom, Jerusalem, PASSIA, 2002.

17. (French) “A la rencontre de Paul. Connaître Paul aujourd’hui : un changement de paradigme ?” Recherches de Science Religieuse, 90/3 (2002), 353-376.

(Spanish) “Reencuentro con Pablo. Un cambio de paradigma?”, Selecciones de teologia, 168 (42/2003), 277-290.

18. (Arabic) “Muraja‘at kutub: As-Sira‘ min ajil al-‘adala (Book Review: The Struggle for Justice),” al-Liqa’ 1-2/17 (2002), 218-230.

19. (English) “Jewish Israeli attitudes towards Christianity and Christians in contemporary Israel,” in World Christianity: Politics, Theology, Dialogues (eds. A. Mahoney and M. Kirwan), London, Melisende Press, 2004, 347-369.

20. (Arabic) “Risalah maftuha ila ru’asa’ina al-diniyyin – al-hakham, al-shaykh wa-al-khuri” (An open letter to our religious leaders: rabbi, shaykh and priest),” al-Liqa’ 18/1-2 (2003), 108-120.

21. (Arabic) “Ma hiyya as-sahyuniyyah al-masihiyyah? (What is Christian Zionism?)”, al-Liqa’ 19/1-2 (2004), 100-116.

(English) Al-Liqa’ Journal vol. 23 (December 2004), 17-32.

22. (English) 9 values (Arab Christianity, Elijah, Jacob, Jesuits, Palestinian liberation theology, Ratisbonne brothers, Ratisbonne Institute, Saint James Association, Suffering Servant) in E. KESSLER, and N. WENBORN, A Dictionary of Jewish-Christian Relations, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2005.

23. (English) “A Holy Land Context for Nostra Aetate” (with Jamal Khader), Studies in Jewish Christian Relations, vol. 1 (2005-6), 67-88.

24. (English) “New Wine in Old Wineskins: Russians, Jews and Non-Jews in the State of Israel,” Journal of Eastern Christian Studies, 57/3-4 (2005), 207-236.

25. (Arabic) “Kitabuna al-muqaddas: ma huwa wa-limadha naqra’uhu” (Our Bible: What is it and why do we read it), Itba’uni 4 (Winter 2005), 7-9.

26. (French) “Qehilla, Eglise et people juif,” Proche Orient chrétien, 56 (2006), 53-65.

27. (French) “Le dialogue interreligieux en Terre Sainte quarante ans après Nostra Aetate” (with Jamal Khader), Proche Orient chrétien, vol. 56 (2006), 299-310.

28. (French) La Terre, la Bible et l’Histoire (with Alain Marchadour), Paris, Bayard Presse, 2006.

Simultaneously with:

(English) The Land, the Bible and History (with Alain Marchadour), New York, Fordham University Press, 2007.

(Italian) La Terra, la Bibbia e La Storia (with Alain Marchadour), Rome, Jaca Books, 2007.

(German) Land, Bibel und Geschichte (with Alain Marchadour), Berlin, AphorismaA Verlag, 2011.

(Korean), 2016.

29. (English) “Achievements and Challenges in Jewish-Christian Dialogue: Forty Years after Nostra Aetate” The Downside Review 439 (April 2007), 111-129.

30. (French) “Un mur de discorde,” Relations 717 (juin 2007).

31. (English) “In memoriam: A Righteous Gentile: Marcel Dubois op (1920-2007),”

America, October 1, 2007 (vol. 197/9), 22.

32. (English) “The Holy Family? A biblical meditation on Jesus’ family in the Synoptic Gospels,” in M. Ferrero and R. Spataro (eds), Tuo padre e io ti cercavamo: Studi in onore di Don Joan Maria Vernet (Jerusalem, Studium Theologicum Salesianum, 2007) 33-55.

33. (English) “What might Israelis and Jews learn about Christians and Christianity at Yad VaShem,” in Thomas Michel (ed), Friends on the Way: Jesuits encounter Contemporary Judaism (New York, Fordham University Press, 2007), 166-178.

34. (Italian) “Terra Promessa – Risponde al Patriarca,” in Michel Sabbah, Voce che grida dal deserto (Milan, Paoline, 2008), 38-42.

(Arabic) by Ibrahim Shomali, Sawtun sarikhun fi’l baria (Jerusalem, Latin Patriarchate Printing Press, 2008)

35. (English) “How promised is the Promised Land,” The Word is Life (110 – summer 2008), 6-9.

36. (English) “Israel’s Hebrew speaking Catholics,” ZENIT (8.6.2008).

37. (English) “A dividing wall of hostility in the Holy Land,” in Claudia Lücking-Michel and Stefan Raueiser (eds), Drei Religionen – Ein Heiliges Land (Cologne, Cusanuswerk, 2008), 65-67.

38. (English) “Pope worked a subtle revolution in Paris,” ZENIT (30.9.2008).

39. (French) “Qui est qui ? Russes et juifs en Israël aujourd’hui,” Proche orient chrétien 1-2 / 58 (2008), 21-58.

40. (English) “Getting to know Saint Paul today: A change in paradigm?,” Thinking Faith, posted on internet journal on 27.10.2008.

41. (English) “Paul: A “tentmaker” in M. Ferrero and R. Spataro (eds), Saint Paul: Educator to faith and love (Jerusalem, Studium Theologicum Salesianum, 2008) 147-166.

42. (Hebrew) Yemay Zikaron weHagigah beLuah haShanah HaNotsri (Days of Memorial and Celebration in the Christian Calendar) (Jerusalem, Jerusalem Center for Jewish Christian Relations, 2008).

43. (Italian) “Il papa in Terra santa: sogni e prudenza,” in Popoli (May 2009), 57.

44. (English) “Pope visits Middle East as brother of Muslims and Jews,” ZENIT (7.5.2009).

45. (Italian) with Giorgio Bernadelli, “Pietro e gli ebrei: l’incontro possibile,” Mondo e Missione, 5/138 (May 2009), 24-27.

46. (Italian) with Sergio Rotasperti, “Il Papa in Terra santa,” Testimoni, May 15, 2009, 4-7.

47. (English) “Imagining a new future in the Holy Land,” in ZENIT (19.5.2009).

48. (Français) “L’autre Israël” in Relations, Mai 2009 (n. 732), 23-24.

49. (Polish) “Ewangelizacja I dialog” in Postaniec, Iipiec 2009, 12-26.

50. (English) “Benedict’s visit to a land called to be holy,” Thinking Faith (9.6.2009)

51. (English) “Benedict’s visit to a land called to be holy,” Al’Liqa’ Journal, vol. 32 (June 2009) 113-133.

52. (Arabic) “Ziyarat Benediktus al-Sadis Ashar ila Ard Musama Muqaddasah,” Al Liqa, Vol. 24, numbers 1 and 2 (2009), 254-269.

53. (Hebrew) “Ha-yeshu’i (The Jesuit)”, Kivun n. 66 (July-August 2009), 10-11.

54. (German) “Gespräch mit dem hebräischen Pater David Neuhaus,” Israel Heute, n. 373, 23.

55. (English) “A human sacrifice,” The Jerusalem Post Magazine, 25.9.2009, 17.

56. (English) “Serving Christ in the Holy Land,” ZENIT, 6.11.2009.

57. (French) “Les catholiques en régions arabes et en Israël” ZENIT, 1.12.2009.

58. (Hebrew) Eydot Notsriyot Berets HaQodesh (Christian Communities in the Holy Land) (Jerusalem, Jerusalem Center for Jewish Christian Relations, 2009).

59. (French) “L’identité juive à l’époque modern,” La Terre sainte (n. 604, 75/6), 314-323.

(Italian) “Ebrei Quale identità?” in Terrasanta, IV/3 (May-June 2010), 10-14.

60. (English) “Moments of crisis and grace: Jewish-Catholic relations in 2009,” One In Christ, volume 43/2 (2009), 6-24.

61. (English) “Shimon Balas – A Jewish Arab at 80,” Proche Orient chrétien, 59 (2009), 352-361.

62. (English) “The priest in the Old Testament: Some biblical reflections on the priest,” in Giovanni Caputa and Julian Fox (editors), Priests of Christ in the Church for the World (Jerusalem, Studium Theologicum Salesianum, 2010), 13-44.

63. (French) “Dieu va nous surprendre” – Entretien avec le Père David Neuhaus, La Nef, 213 (mars 2010), 15-17.

64. (English) “Catholic-Jewish Relations in the State of Israel: Theological Perspectives,” in Anthony Mahoney and John Flannery (editors), The Catholic Church in the Contemporary Middle East (London, Melisende Press, 2010), 237-251.

65. (English) “Engaging the Jewish People – Forty Years since Nostra Aetate,” Karl Becker and Ilaria Morali (editors), Catholic Engagement with World Religions: A comprehensive study (New York, Orbis Books, 2010) 395-413.

66. (Italian) “Otto sfide,” Popoli (2010/10), 55-56.

67. (French) “Où se trouve la fête de Soukkot dans la tradition chrétienne,” La Terre sainte, n. 609 (septembre – octobre 2010), 278-279.

68. (French) “La foi chrétienne et l’hébreu en commun,” La Terre sainte, n. 609 (septembre – octobre 2010), 280-281.

69. (Italian) “Come essere cattolici, parlare ebraico e vivere nella società israeliana,” La Voce dei Berici, 26.12.2010, 24-25.

70. (Italian) “Piccoli cattolici crescono,” Popoli (2010/12), 56-58.

71. (Hebrew) Haker et haKnaysiyah (Get to Know the Church), Beit Jala, Latin Patriarchate Printing Press, 2010.

72. (English) “Jewish Identity in the Modern Age,” The Holy Land Review, 2/4 (Spring 2011), 10-14.

73. (Arabic) “Taarikh al-Khalas huwa qisat hub bayna Allah wa-shaabihi,” As-Salaam wa-l-Khayr 4/71 (July-August 2011), 38-44.

74. (Italian) “Intervista a Padre David Neuhaus,” in Renzo Fabris, Gli ebrei cristiani (Magnano, Edizioni Qiqajon, 2011), 161-173.

75. (English) “The use of the Bible to justify violence,” Jamal Khader and Angela Hawash – Abu Eita (eds), Violence, Non-Violence and Religion (Bethlehem, Bethlehem University, 2011) 141-146.

76. (French) “Dieu va nous surprendre” – Entretien avec le Père David Neuhaus,” Falk van Gaver et Kassam Maadi, Terre sainte, guerre sainte? (Paris, La Nef, 2011), 141-146.

77. (French) “Le Synode pour le Moyen Orient et les relations judéo-chrétiennes,” Proche Orient chrétien, 61 (2011), 319-332.

78. (Hebrew) Kaker et haHaggim wehaMoadim baKnaysiyah (Get to Know the Feasts and the Seasons in the Church), Beit Jala, Latin Patriarchate Printing Press, 2011.

79. (English) “The Word of God in Joshua 6: The Destruction of Jericho,” in Avital Wohlman and Yossef Schwartz (eds), Le chrétien poète de Sion: In memoriam Père Marcel-Jacques Dubois (Jerusalem, Van Leer Institute, 2012) 149-181.

80. (English) “Where is the Word of God in the Book of Joshua? An essay on a canonical reading of Josh 6,” in Joachim Negel and Margareta Gruber (eds), Figuren der Offenbarung (Munster, Aschendorff Verlag, 2012) 25-59.

81. (English) “Christian-Jewish Relations in the Context of Israel-Palestine”, Cornerstone number 64 (Winter 2012), 6-8.

82. (Hebrew) Haker et Se’udat ha’Adon, Beit Jala, Latin Patriarchate Printing Press, 2012.

(Italian) Conosci la Cena del Signore, Il pozzo di Giacobbe, Trapani, 2018.

83. (Spanish) “O papel religioso no conflito do mundo árabe (The role of religion in the conflict in the Arab world,” IHU-On Line, number 408 (12.11.2012).

84. (Arabic) Nata’arifu ‘ala Yasu’ min khilal Injil al-Qadis Luqa (Let us get to know Jesus by means of the Gospel of Saint Luke) Beit Jala, Manshurat Maktabat Yasu’ al-Malik, 2013.

85. (English) “The Challenge of New Forms of Christian Presence in the Holy Land,” in Timothy Lowe (ed), Hope of Unity: Living Ecumenism Today, Celebrating 40 years of the Ecumenical Institute Tantur, Berlin, AphorismA, 2013, 133-145.

86. (Italian) “Gli ultimi anni di Cardinal Martini – Testimonianze,” in Carlo Maria Martini – da Betlemme al cuore dall’uomo – Lectio divina in Terra Santa, Milan, ETS, 2013, 75-78.

87. (Hebrew) Lehakir et Toldot haYeshu’a, Beit Jala, Latin Patriarchate Printing Press, 2012.

(Arabic) Riwayat min al-kitab al-muqadas, Dar al Mashriq, Beirut, 2018.

(Italian) Conosci la storia della salvezza, Il pozzo di Giacobbe, Trapani, 2018.

88. (Arabic) Nata’arifu ‘ala Sifr A’amal ar-Rusul (Let us get to know the Book of the Acts of the Apostles) Beit Jala, Manshurat Maktabat Yasu’ al-Malik, 2014.

89. (English) “Horizons beyond Walls: Pope Francis in the Holy Land,” Thinking Faith (June, 2014).

90. (English) “Jewish-Christian Relations in West Asia: History, Major Issues, Challenges and Prospects,” in Felix Wilfred (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Christianity in Asia, Oxford University Press, New York, 2014, 368-378.

91. (Arabic) Nata’arifu ‘ala Sifr al-Ru’iya’ (Let us get to know the Book of Revelation) Beit Jala, Manshurat Maktabat Yasu’ al-Malik, 2014.

92. (Arabic) “Ihdamu judran al-ada’: al-Baba Fransis fi Isra’il (Tear down the walls of enmity: Pope Francis in Israel),” Al-Liqa’, 3/29 (2014), 128-142.

(English) “Tear down the walls of enmity: Pope Francis in Israel,” Al Liqa Journal, 43 (December 2014), 84-100.

93. (English) “The Occupation of the Bible: Biblical Authority,” in Naim, Attek, Cedar Duaybis and Tina Whitehead (eds), The Bible and the Palestine Israel Conflict, Jerusalem, Sabeel Ecumenical Liberation Theology Center, 2014, 49-52.

94. (French) “L’étau du conflit israélo-palestinien” in Jean-Michel Falco, Tomothy Radcliffe and Andrea Ricardi (eds), Le livre noir de la condition des chrétiens dans le monde XO Editions, Paris, 2014, 308-321.

95. (English) “”So that they may be one”: Ecumenism in Israel Palestine Today,” Mishkan 72 (2014), 2-8.

96. (Hebrew) “Kol Holem hu Boged (Every Dreamer is a Betrayer)” in HaAretz (Books), 28.11.2014, 2-3.

97. (French) “L’avenir des chrétiens au Moyen-Orient: Une vision depuis la Terre Sainte”, Études, 2014/12 Tome 420, p. 63-72.

Also published in: Jerusalem, 2015/1-3 volume 82, 34-41.

(Italian) “L’avvenire dei cristiani in Medio Oriente,” La Civilta cattolica, 3.1.2015 (3949), 56-65.

(English) “The Future of Christians in the Middle East: A view from the Holy Land,” Thinking Faith (9.2.2015).

98. (English) “Jesus: Who Do You Think You Are? 2. Rahab, Ruth and Boaz” Thinking Faith (11.12.2014).

99. (English) “Alternatives on a Horizon Beyond Walls: Pope Francis in the Holy Land,” Proche Orient chrétien 2014, 64/1-2, 54-68.

100. (English) “Jewish-Christian Dialogue in Israel Today: When Jews are the Majority,” in Ron Kronish (editor), Coexistence and Reconciliation in Israel: Voices for Interreligious Dialogue, New York, Paulist Press, 2015, 73-85.

101. (English) “The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem: Peacemaking in a time of conflict,” Proche orient chrétien 64 (2014), 291-310.

102. (Arabic) Nata’arifu ‘ala Asfar al-Hikma (Let us get to know the Books of Wisdom) Beit Jala, Manshurat Maktabat Yasu’ al-Malik, 2015.

103. (English) “The Holy See and the State of Palestine” Thinking Faith (21.5.2015).

104. (Italian) “La Santa Sede e lo Stato di Palestina,” Civiltà cattolica, 2015 III (3961, 11.7.2015), 72-79.

(French) « Le Saint-Siège et la Palestine, » Choisir n. 670 (octobre 2015), 24-28.

105. (English) “So that they be one – New ecumenical dilemmas in Israel-Palestine today,” Proche orient chrétien, volume 65 (2015), 1/2, 45-58.

106. (French) “Le dialogue juifs-chrétiens et la question de la Terre d’Israël,” Recherches de science religieuse, tome 103 (2015), 3, 397-418.

107. (Arabic) “Ar-rahmah wa-ar-rafah” (Mercy and compassion) in Rafiq Khoury (ed), Ta’amulat fi ar-rahmah (Meditations on Mercy), Beit Jala, Manshurat Maktabat Yasu’ al-Malik, 2015, 16-20.

108. (Italian) “Gli Ebrei che credono in Gesù. Il Dialogo tra Cattolici ed Ebrei Messianici,” Civiltà cattolica, 2015 IV (3968, 24.10.2015), 145-156.

109. (English) “Doing Theology Today,” Jérusalem (July-August-September 2015) 214-216.

110. (French) “50 ans Nostra Aetate : quel dialogue interreligieux pour la Terre sainte ?” Jérusalem (October-November-December 2015) 292-296.

111. (English) “Mighty God,” Thinking Faith (14.12.2015).

112. (French) “La petite arabe et les chretiens hébréophones,” Carmel, n. 158 (2015), 80-89.

113. (Hebrew) “Slihah shehitavarnu (Sorry that we were blind),” in HaAretz (Books), 29.1.2016, 10.

114. (Hebrew) “Hulsha weAmbivalentiut (Weakness and ambivalence),” 929, (4.2.2016), http://www.929.org.il/page/295/post/8043

115. (English) “Christian Peace-making in Israel-Palestine Today,” Live Encounters (March 2016), 12-17.

116. (French) “L’œuvre Saint-Jacques : Soixante ans,” Proche orient chrétien, volume 66 – 2016, 1/2, 45-59.

117. (English) “The new challenges of the Saint James Vicariate,” Jerusalem Bulletin diocesain du Patriarcat Latin 7-9/83 (July to September 2016), 257-261.

118. (English) “Towards the Ends of the Earth: Land in the Jewish-Christian Dialogue,” Jerusalem Bulletin diocesain du Patriarcat Latin 10-12/83 (October to December 2016), 355-370.

119. (English) “Who are the Christians of Israel today,” Jerusalem Bulletin diocesain du Patriarcat Latin 10-12/83 (October to December 2016), 377-388.

120. (Arabic) Nata’arifu ‘ala al-Qadis Bulus wa-rasa’ilihi (Let us get to know Saint Paul and his epistles) Beit Jala, Manshurat Maktabat Yasu’ al-Malik, 2016.

121. (French) Je vous écris de la Terre Sainte, Paris, Bayard Presse, 2017.

122. (Hebrew) “Zechor et ha-Filipinim (Remember the Filipinos),” HaAretz, 10.2.2017.

123. (Hebrew) “Yeshu o Yeshua”, Musaf HaAretz, 6 (24.3.2017).

Published also in English: “The Man from Nazareth: Yeshu or Yeshu’a”, Jewish-Christian Relations (1.11.2017), http://www.jcrelations.net/The_Man_from_Nazareth__Yeshu_or_Yeshu___a.5860.0.html?L=3

124. (English) “Choose life, horizons beyond the tomb walls,” Thinking Faith (20.4.2017).

125. (English) “How promised is the Promised Land?” Bible Bhashyam, volume 43, no. 1-2 (March-June 2017), 3-9.

126. (Italian) “Un ricordo di padre Marcel Dubois,” in Marcel-Jacques Dubois, La spiritualità del giudaismo, Milan, Edizione Terra Santa, 2017, 7-14.

127. Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Guide Book, (with Biju Michael and Lionel Goh), Jerusalem, STS Publications, 2017 (in multiple languages).

128. (English) Mercy: A Christian Way of Life – Essays in Honor of Dr. Biju Michael SDB, editor with Romero D’Souza, Jerusalem, STS Publications, 2017.

129. (English) Writing from the Holy Land, Jerusalem, STS Publications, 2017.

130. (French) “Jérusalem après Trump,” Choisir (18.12.2017),

https://www.choisir.ch/politique-economie/politique-internationale/item/3057-jerusalem-apres-trump

131. (Arabic) Nata’arifu ‘ala al-Kutub al-Khamsa (Let us get to know the Pentateuch) Beit Jala, Manshurat Maktabat Yasu’ al-Malik, 2017.

132. (Italian) “Gerusalemme e la Chiesa Cattolica (Jerusalem and the Catholic Church)”, Civiltà cattolica, 2018 I (4021, 6.1.2018), 10-23.

also in English: “The Catholic Church and the Holy City,” Civiltà cattolica, 2018 II (3, 18.3.2018).

133. (Portuguese) “Jerusalém, cidad santa, zona de guera (Jerusalem, holy city, war zone)ˮ, Brotéria, 186/1 (January 2018), 45-48.

134. (English) “Jerusalem: The Catholic Church and the Holy City,” Jewish Christian Relations, 1.5.2018, http://www.jcrelations.net/Jerusalem__The_Catholic_Church_and_the_Holy_City.5985.0.html?L=3

135. (English) “Israel” in Kenneth Ross, Mariz Radros and Todd Johnson (editors), Christianity in North Africa and West Asia, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2018, 127-139.

136. (English) “A Christian view of Jerusalem: The Catholic Church and the Holy City,” Justice (Spring 2018), no. 60, pp. 26 – 31.

137. (English) “A Personal Reflection on Dialogue with Muslims – an experience in Jerusalem,” Proche orient chrétien, volume 68 (2018), 1/2, 115-131.

138. (Italian) Dialogo a Gerusalemme (Dialogue in Jerusalem), Bologna, Edizioni Zikkaron, 2018.

139. (Italian) Vi scrivo dalla Terra santa (I write to you from the Holy Land), Bologna, Edizioni Zikkaron, 2018.

140. (Italian) Riflessioni bibliche (Biblical Reflections), Bologna, Edizioni Zikkaron, 2018.

141. (Arabic) Nata’arifu ‘ala Yasu’ fi Injil al-Qadis Murqus (Let us get to know Jesus in the Gospel of Saint Mark) Beit Jala, Manshurat Maktabat Yasu’ al-Malik, 2018.