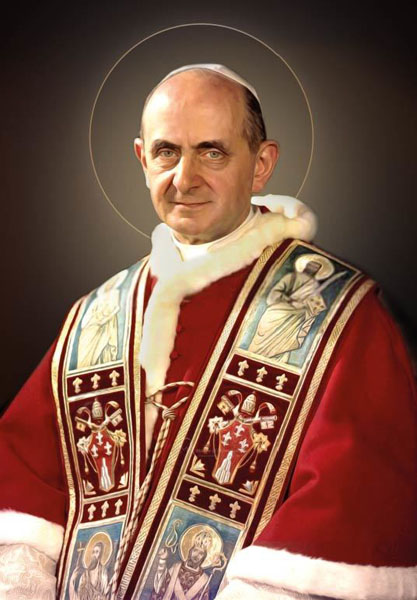

PAUL VI and Gandhi, Kindred Maha-Spirits by Dr Peter Gonsalves

Peter Gonsalves, PhD, teaches the Sciences of Social Communication at Salesian University, Rome. This extract is taken and adapted from the last volume of his Gandhian trilogy, Gandhi and the Popes: from Pius XI to Francis (Peter Lang publishers, 2015). He may be visited at www.petergonsalves.in

Giovanni Battista Montini, later better known as Pope Paul VI, may have never met Mahatma Gandhi in person even though the latter visited Rome in 1931, but there is some striking evidence to prove that he admired, and even drew inspiration from Gandhi’s life and teachings.

Giovanni Battista Montini, later better known as Pope Paul VI, may have never met Mahatma Gandhi in person even though the latter visited Rome in 1931, but there is some striking evidence to prove that he admired, and even drew inspiration from Gandhi’s life and teachings.

He was the first pope to set foot on Indian soil with his arrival in Bombay on December 2, 1964, barely seventeen years after India was freed from colonial rule. As pope, it was his responsibility to lead and conclude the Second Vatican Council and to initiate the long, tedious and extremely challenging process of promulgating its vision and directives. Two of the many areas that needed particular attention were interreligious dialogue and matters concerning sexuality and marriage. On both these issues, his teaching bears marked affinity with Gandhian thought.

With Gaudium et Spes (1965), the Council’s Pastoral Constitution, the tone was set for dialogue with all persons of good will. It would seem that the Council Fathers, fully aware of the struggle for India’s liberation, had the nonviolent Mahatma in mind when they declared: “All Christians are urgently summoned to do in love what the truth requires, and to join with all true peacemakers in pleading for peace and bringing it about. Motivated by this same spirit, we cannot fail to praise those who renounce the use of violence in the vindication of their rights.”[1] The document, Nostra Aetate (1965), goes a step further. As the Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions, it singles out Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Judaism and other faiths as opportunities for dialogue. “The Catholic Church rejects nothing which is true and holy in these religions… [They] often reflect a ray of that Truth which enlightens all people.”[2] The document categorically states, “The Church reproves, as foreign to the mind of Christ, any discrimination against persons or harassment of them because of their race, color, condition of life, or religion.”[3]

Pope Paul VI’s own encyclical, Populorum Progressio (1967), is a milestone in its focus on holistic development for all peoples, especially those emerging from years of subjugation under colonialism. It was a clarion call for a globalization of progress in which all nations would have a stake. “We cherish this hope: that distrust and selfishness among nations will eventually be overcome by a stronger desire for mutual collaboration and a heightened sense of solidarity.”[4]

In 1969, the centenary year of Mahatma Gandhi’s birth, Paul VI paid rich tributes to the Father of the Indian Nation in a letter to the President of India, Varahagiri Venkata Giri.

Gandhi had a high appreciation of the value of human dignity, and a keen sense of social justice. With warm zeal and a clear vision of the future welfare of his people, he worked tirelessly to achieve his goals, ever instilling in his followers the admirable principle of non-violence. He strove to make his countrymen conscious of injustices in their social system, and to spread among them a spirit of equality and brotherhood. His efforts and example, even when not entirely successful, have left their mark upon the men of his own and our generation.[5]

In matters concerning sexual morality, Pope Paul VI published his historic encyclical Humane Vitae,[6] in which he made the practice of spousal chastity the bedrock of the ideal Christian marriage. He propagated “responsible parenthood” based on an aspect of “paramount importance”: the formation of “a right conscience [as] the true interpreter” of God’s purpose for a healthy family life. This depended on self-control and the method of Natural Family Planning, rather than the use of artificial contraception. As an example, he pointed to Gandhi’s choice for ‘conjugal chastity’, that provided the inner strength to lead by example in an extremely complex and volatile socio-political context.[7]

Gandhi expressed his own opinion on the matter in his autobiographical series published between 1925 and 1929 in his journal ‘Navjivan’. Looking back at the nearly twenty years of keeping the brahmacharya vow, he admitted that it filled him with “pleasure and wonderment”. The power of celibacy for achieving greater things became self-evident: “The freedom and joy that came to me after taking the vow had never been experienced before 1906”[8] – the year he began satyagraha in South Africa. He also observed the same power at work in those who took the vow and, contrarily, in those who did not. In an interview with Ramachandran, a student of Gandhi’s good friend, the Rev. C. F. Andrews, asked him if he was against the institution of marriage since he consistently advocated celibacy, which the Anglican pastor disapproved.

Gandhi: Yes, I know [that Andrews disagrees]. That is the legacy of Protestantism. Protestantism did many good things, but one of its few evils was that it ridiculed celibacy.

Ramachandran: That was because it had to fight the deep abuses in which the clergy of the age had sunk.

Gandhi: But all that was not due to any inherent evil of celibacy. It is celibacy that has kept Catholicism green up to the present day.[9]

Yet again, when citing the extraordinary accomplishments that one who practices sexual self-discipline is capable of, Gandhi holds up unmarried Catholic educators (numerous during his time) as models to be imitated. His audience consists of rich Indians ever eager to multiply profits rather than share their wealth by sponsoring the free education of their less fortunate brothers and sisters.

Making money is not the object of education. If the Roman Catholic community is foremost in the world in the matter of education, it is so because it has from the beginning decided that those who are to be engaged in teaching should give their services free, accepting only what is necessary for their maintenance. Besides, they are of mature age and unmarried, so that they are able to devote all their time to the single job of teaching. We may or may not be able to reach that level, but there is no doubt that we ought to take a lesson from their example.[10]

Furthermore, Gandhi predicted the sexual revolution that would give rise to all kinds of promiscuities once artificial means of birth control became popular. “Artificial methods are like putting a premium upon vice. They make man and woman reckless.… The remedy will be found to be worse than the disease.”[11]

At the heart of Humane Vitae, however, is the appeal for an education of one’s conscience to moral responsibility. And to hear one’s conscience, interior silence is necessary. The Pope recalls how Socrates was profoundly attuned to his conscience – that divine voice for which he was accused of having a ‘demon’. Then he adds: “Gandhi [too] obeyed a ‘still small voice’ which in certain moments made itself heard within him.”[12]

Besides the two above-mentioned issues that united Paul VI and Gandhi as kindred spirits, he was also concerned about India’s development. For instance, there is evidence to prove that he did much to alleviate the drought and food shortage that threatened India in 1966. He sent a personal gift of $ 100,000 to the Government of India; he wrote to the President of the United States to give India special consideration; he appealed to various Catholic relief organizations as well as to UNICEF to increase their aid to India, and requested his own Office for the Propagation of the Faith to dispatch a shipment of food.[13]

India’s national leaders, most of whom were close collaborators of Mahatma Gandhi, were deeply moved by the Pope’s solicitude. In March 1968, a confidential memorandum was sent to the Vatican Secretariat of State to learn whether the Holy Father would be willing to accept the newly created ‘Nehru Award’ set up by the Indian Government to honour the world’s most distinguished promoters of international peace.[14] The 1968 Award, the memorandum said, was “unanimously proposed to be made to the Holy Father.” A few days later, the Vatican’s Secretariat of State replied that “the present Holy Father has established the practice of not accepting awards and prizes of this nature” and that he was, of course, “profoundly grateful” to the Vice President and the Prime Minister of India and the distinguished members of the jury for proposing his name.[15]

On January 30, 1978, the thirtieth anniversary of Gandhi’s assassination, Paul VI sent a pertinent message to the Indian people through All India Radio: “No to violence, Yes to Peace!… To reject violence and to accept all the conditions and demands of Peace is an activity of the highest dignity; it is an expression of the truest patriotism. May God give his peace to India. May the love and peace of God abide in your hearts forever!”[16] The message turned out to be his parting gift to India. He breathed his last on August 6, 1978.

Today, forty years later, we are happy to acclaim him a Maha-Atma, a Great Soul, a Saint of the Catholic Church for all people of good will!

[1] Vatican Council II, “Gaudium et Spes”, AAS, 58, no. 78 (1966) 1025-1115. See official English translation in Vatican.va, 1965, http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html (03-02-2013)

[2] Lloyd I. Rudolph, “Gandhi in the Mind of America” in Richard L. Johnson (Ed), Gandhi’s Experiments with Truth, Essential Writings by and about Mahatma Gandhi, Oxford, Lexington Books, 2005, 281.

[3] Vatican Council II, “Nostra Aetate”, AAS, 58, no. 5 (1966) 743-744.

[4] Pope Paul VI, “Populorum Progressio”, March 26, 1967, art. 64 in, http://w2.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-vi_enc_26031967_populorum.html

[5] Paul VI, “Letter of Paul VI too His Excellency Varahigiri Venkata Giri, President of India”, L’Osservatore Romano, 3-10-1969, 1.

[6] Paul VI, “Humanae Vitae”, AAS, 60 (1968) 481-503. See English translation in Vatican.va, http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-vi_enc_25071968_humanae-vitae_en.html (05-06-2013)

[7] In an earlier study, I had underscored the argument that “it was primarily this rigorous discipline of subverting his own bodily and worldly instincts that would give him the fearlessness and determination to subvert violent empires and unjust social structures.” Peter Gonsalves, Khadi: Gandhi’s Mega Symbol of Subversion, New Delhi, Sage Publications, 2012, 199.

[8] Autobiography, Ahmedabad, Navajivan Trust, 2005, 192.

[9] CWMG, vol. 25, 252-253.

[10] CWMG, vol. 6 (1907) 268.

[11] CWMG, vol, 26, 280.

[12] Paolo VI, “Udienza Generale, Mercoledì, 17 maggio 1972” in, Vatican.va, (trans. mine), http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/audiences/1972/documents/hf_p-vi_aud_19720517_it.html (02-02-2013).

[13] Cf. Letter, protocol no. 62891, marked ‘Confidential’ to Rev. Jerome D’souza S.J. from the Segreteria di Stato di Sua Santità, Vatican, January 25, 1966 in File no. JER. D’S 39/bis, JEMPARC, Shenbaganur, India.

[14] The ‘Nehru Award’, the confidential memorandum stated, “is adjudged by a distinguished jury, the Chairman of which is the Vice President of India. The Award is accompanied by a cash prize of Rs. 100,000. The first Award was made to U. Thant last year [1967] and he went to Delhi to receive it. There is a citation on the achievements of the Recipient, and a suitable reply.” See “Letter to the Secretary of State” sent by Fr J. D’Souza, 23-03-1968 in, File no. JER. D’S 38, JEMPARC, Shenbaganur, India

[15] Letter of Secretariat of State (signed: Pinome Becuì, Subst.) to Fr. J. D’Souza, 13-04-1968, protocol no. 98264, in File JER. D’S 38, JEMPARC, Shenbaganur, India.

[16] Pope Paul VI, “Address of the Holy Father Paul VI to the Indian People in Honour of Gandhi”, in Vatican.va, 30-01-1978, http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/speeches/1978/january/document/hf_p-vi_spe_19780131_popolo-indiano_en.html (20-12-2012).

© Dr Peter Gonsalves