Bhagat Singh and his revolutionary inheritance by Professor S Irfan Habib

S Irfan Habib is an Indian historian of science, a widely published author, and a public intellectual. He was the Abul Kalam Azad Chair at the National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration (NIEPA), New Delhi. Before joining NIEPA, he was a scientist at the National Institute of Science, Technology and Development Studies (NISTADS), New Delhi.

SAGE India: https://in.sagepub.com/en-in/sas/inquilab/book266566

SAGE UK: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/inquilab/book266566

SAGE US: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/inquilab/book266566

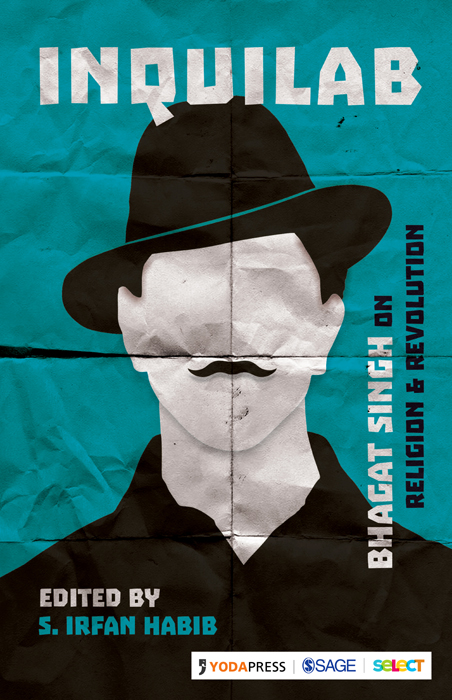

Bhagat Singh has always evoked unbounded approbation and respect across India. He is, if I am not exaggerating, one of the most widely respected nationalist icons after Mahatma Gandhi. Most of us rightly valorise him for his martyrdom but in the midst of this euphoric celebration of the man we forget about his intellectual legacy. He not only sacrificed his life, like many did before him and also after him, but he also had a vision of independent India. The past few decades have seen appropriation of Bhagat Singh’s nationalist image by diverse groups from extreme right to the extreme left and of course by a huge section of common Indians as well. We need to know that Bhagat Singh was not just a patriot, with a passionate commitment to his nation, he was a visionary, with a pluralist and egalitarian perception of independent India. This new volume titled Inquilab is committed to emphasize this particular aspect of Bhagat Singh’s persona, which I suspect is consciously and conveniently ignored by those who love to venerate him merely as a raw nationalist.

Bhagat Singh has always evoked unbounded approbation and respect across India. He is, if I am not exaggerating, one of the most widely respected nationalist icons after Mahatma Gandhi. Most of us rightly valorise him for his martyrdom but in the midst of this euphoric celebration of the man we forget about his intellectual legacy. He not only sacrificed his life, like many did before him and also after him, but he also had a vision of independent India. The past few decades have seen appropriation of Bhagat Singh’s nationalist image by diverse groups from extreme right to the extreme left and of course by a huge section of common Indians as well. We need to know that Bhagat Singh was not just a patriot, with a passionate commitment to his nation, he was a visionary, with a pluralist and egalitarian perception of independent India. This new volume titled Inquilab is committed to emphasize this particular aspect of Bhagat Singh’s persona, which I suspect is consciously and conveniently ignored by those who love to venerate him merely as a raw nationalist.

Bhagat Singh left behind a rich intellectual legacy despite the fact that he hardly had time to read and write. He began writing at a very young age and was a voracious reader who always carried few books in his pockets. Many of his writings are available in Hindi and also few in English but a comprehensive collection for English readers was not around. This volume will show that Bhagat Singh did not merely yearn for an independent India but an India that will be egalitarian and secular. This was reflected in his revolutionary activities as well as in his commitment as a sensitive journalist. This collection of his writings will be a window, where the reader will be able to peep into the most important yet neglected aspect of Bhagat Singh’s nationalist and revolutionary legacy.

Unlike many of the young generation today, he was not in a hurry to write without reading enough on the subject. As I pointed out earlier, Bhagat Singh was a voracious reader, who devoured anything new which was published on poverty, religion, society and global struggle against imperialisms. He seriously debated and discussed what he read and also wrote extensively on issues of caste, communalism and conditions of the working class and peasantry.

The profundity of his ideas on some of the above mentioned issues is visible in his regular columns in Kirti, Pratap and other papers. On an issue like religion and our freedom struggle, he had very clear ideas. In one of the articles on this subject he spoke about Tolstoy’s division of religion into three parts: essentials of religion, philosophy of religion and rituals of religion. He concluded that if religion means blind faith by mixing rituals with philosophy than it should be blown away immediately but if we can combine essentials with some philosophy than religion may be a meaningful idea. He felt that ritualism of religions had divided us into touchables and untouchables and these narrow and divisive religions can’t bring about actual unity among people. For us freedom should not mean mere end of British colonialism, our complete freedom implies living together happily without caste and religious barriers. Bhagat Singh need to be invoked even today to bring about changes he yearned for. Expressing his anguish in another article, he held some of the political leaders and the press responsible for inciting communalism. He believed that “there were a few sincere leaders, but their voice is easily swept away by the rising wave of communalism. In terms of political leadership, India had gone totally bankrupt”.

It is not something unusual that we find huge problems with the ethics and functioning of journalism as a profession, Bhagat Singh did not speak very kindly about it even in the 1920s. He felt that journalism is no more a noble profession as it used to be, when he wrote that “the real duty of the newspapers is to educate, to cleanse the minds of people, to save them from narrow sectarian divisiveness, and to eradicate communal feelings to promote the idea of common nationalism. Instead, their main objective seems to be spreading ignorance, preaching and propagating sectarianism and chauvinism, communalizing people’s minds leading to the destruction of our composite culture and shared heritage”.

Even his commitment to Inquilab/Revolution was not merely for a political revolution but aimed at a social and economic revolution. He saw an India where the 98 percent would rule instead of elite 2 percent. His azaadi was not limited to the expelling of the British; instead he desired azaadi from poverty, azaadi from untouchability, azaadi from communal strife and azaadi from any other discrimination and exploitation. Just twenty days before his martyrdom on 3 March1931 Singh sent out an explicit message to the youth saying:

“…the struggle in India would continue so long as a handful of exploiters go on exploiting the labour of the common people for their own ends. It matters little whether these exploiters are purely British capitalists, or British and Indians in alliance, or even purely Indians.”

Bhagat Singh’s intellectual evolution matures while he was in prison. He read extensively anything from history, philosophy, and economics to literature which is reflected in the Prison diary he left behind. He also wrote a classic essay called “Why I am an Atheist”, in the prison, which was surreptitiously sent out and published in The People on September 27 1930. This essay was not only about his engagement with the idea of God but also underlined his vision of India. In a country where majority of the ideologues of nationalism, as reflected in its current usage as well, used one religion or the other to buttress their idea of nationalism, Bhagat Singh as an iconic nationalist showed that religion was not necessarily an imperative for nationalism or for being a nationalist. Bhagat Singh, as he explains in the essay, began as a believer, who regularly chanted Gayatri Mantra, but gradually realized the futility of religion. And he did that quite early in his life as he proclaims that “My atheism is not of so recent origin. I had stopped believing in God when I was an obscure young man”. Thus most of his quintessential revolutionary nationalism was not underpinned by any religious faith.

Another crucial indicator for the present times in this essay is Bhagat Singh’s commitment to rationalism and critical thinking. He was not for a blind flag waiving nationalism, which many of our jingoists need to remember when they revel in his name. His nationalism was embedded in the idea of progress where there is scope for criticism, disbelieve and capacity to question everything of the old faith. He was uncompromising on this when he said that “mere faith and blind faith is dangerous: it dulls the brain and makes a man reactionary. A man who claims to be a realist has to challenge the whole of the ancient faith. If it does not stand the onslaught of reason it crumbles down.” That clearly means that silencing rationalists can’t be nationalism. Nor defending obnoxious religious practices be nationalism. This essay was not just a harangue against God, it also unconsciously laid down the framework for the youth as well as the idea of progressive nationalism.

Bhagat Singh, in this article, also questions those who found any criticism of leaders like Mahatma Gandhi as blasphemous. He saw hero worship as regressive politics and never perceived any leader as infallible. Our “nationalists” today need to take clue from this illustrious nationalist whom they rightly idolize. He goes on to say that “Criticism and independent thinking are the two indispensable qualities of a revolutionary…. Whether you are convinced or not you must say, “Yes, that’s true”. This mentality does not lead towards progress. It is rather too obviously, reactionary.” Thus nationalism cannot be an uncritical exaltation of either religion, culture, leader or anything else in the name of nation and nationalism.

This collection, which has been aptly titled Inquilab: Bhagat Singh on Religion and Revolution should go a long way to establish him further as an intellectual and a young visionary. Many of his ideas are relevant even today, which means how precious little we have been able to do all these years to eradicate the evils of caste, communalism and poverty. We should remember Bhagat Singh with pride and reflect on the alternative framework of governance he had in mind where social and economic justice — and not terrorism or violence – would be supreme. His commitment to socialism may not appear very attractive in the changing era of globalization, yet his concern for the socio-economically deprived sections still commands attention. Moreover, his passionate desire to rise above narrow caste and religious considerations was never as crucial as it is today.

© Professor S Irfan Habib