Australia: An Old Space Player with a brand-New Space Agency but no Great Futuristic Vision by Dr Namrata Goswami

Dr. Namrata Goswami is an author, strategic analyst and consultant on counter-insurgency, counter-terrorism, alternate futures, and great power politics. After earning her Ph.D. in international relations, she served for nearly a decade at India’s Ministry of Defense (MOD) sponsored think tank, the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), New Delhi, working on ethnic conflicts in India’s Northeast and China-India border conflict. She is the author of three books, “India’s National Security and Counter-Insurgency”, “Asia 2030” and “Asia 2030 The Unfolding Future.” Her research and expertise generated opportunities for collaborations abroad, and she accepted visiting fellowships at the Peace Research Institute, Oslo, Norway; the La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia; and the University of Heidelberg, Germany. In 2012, she was selected to serve as a Jennings-Randolph Senior Fellow at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), Washington D.C. where she studied India-China border issues, and was awarded a Fulbright-Nehru Senior Fellowship that same year. Shortly after establishing her own strategy and policy consultancy, she won the prestigious MINERVA grant awarded by the Office of the U.S. Secretary of Defense (OSD) to study great power competition in the grey zone of outer space. She was also awarded a contract with Joint Special Operations University (JSOU), to work on a project on “ISIS in South and Southeast Asia”. With expertise in international relations, ethnic conflicts, counter insurgency, wargaming, scenario building, and conflict resolution, she has been asked to consult for audiences as diverse as Wikistrat, USPACOM, USSOCOM, the Indian Military and the Indian Government, academia and policy think tanks. She was the first representative from South Asia chosen to participate in the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies NATO Partnership for Peace Consortium (PfPC) ‘Emerging Security Challenges Working Group.’ She also received the Executive Leadership Certificate sponsored by the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, National Defense University (NDU), and the Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies (APCSS). Currently, she is working on two book projects, one on the topic of ‘Ethnic Narratives’, to be published by Oxford University Press, and the other on the topic of ‘Great Power Ambitions” to be published by Lexington Press, an imprint of Rowman and Littlefield.

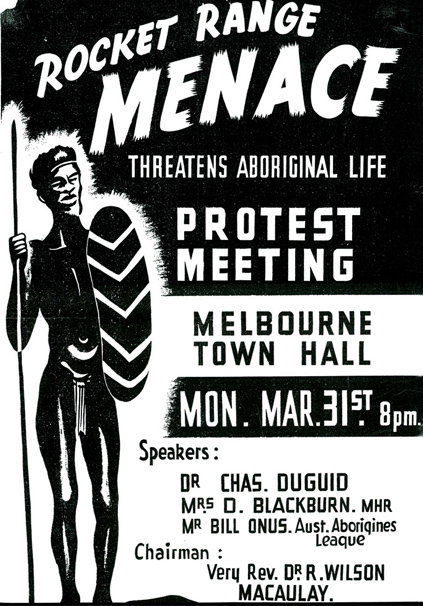

Collaborating for Indigenous Rights,

On July 1, 2018, Australia got a brand-new space agency; the Australian Space Agency (ASA).[1] With access to a budget of $41 million over four years, the ASA is focused on ensuring that Australia has a piece of the cake, of the profitable commercial space sector. And why not? Estimates on the resources awaiting humanity in space to be mined are worth trillions of dollars,[2] and whichever country can crack the technology of gaining cost-effective access and ability to not only explore but mine those resources will benefit most. In 2015, the U.S. established legislation that enables its commercial space sector to explore and own resources from an asteroid.[3] Luxembourg is the only country in Europe that has established similar legislation that supports asteroid mining and back those that lay claim to those resources,[4] within the legal stipulation of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST).[5] But from what I gather from an analysis of the ASA’s mission statement and goals, Australia’s focus is not on that futuristic space industrialization but more on the already existing $329 billion space commerce industry worldwide.[6] To be fair, ASA’s head, Dr. Megan Clark in her message about ASA stated

No other industry can inspire nations quite like space, where human ambition can set its sights on interplanetary missions, colonisation beyond Earth and the opportunity of finding new life. We can dream this big because of the space-based technologies that have connected the world in unprecedented ways, and in the coming decades Australia has the opportunity to become a global leader in pushing Earth’s links with space even further.[7]

However, while she referred to interplanetary missions, and colonization beyond earth, the mission statement of the ASA reflects none of those as of priority. The ASA’s main mission is to lead international space engagement, especially highlighting the importance of space to the national economy, create Space Situation Awareness (SSA), and space debris monitoring, and inspire space entrepreneurs. This focus on space commerce and its link to national development follows the model of countries like China and India where their space programs are directly linked to national development goals. Significantly, given the lucrative nature of the space industry today, Australia wants to take advantage of that by crafting a National Space Policy and by establishing a Space Agency.[8] The motivation behind the move is also to catch up with neighbors like New Zealand that established its space agency in 2016,[9] and its space startup Rocket Lab plans to launch rockets soon.[10]

To be sure, Australia is not a new entrant to the enterprise of space. It launched its first satellite, WRESAT, into orbit in 1967,[11] even before China and India launched theirs in 1970 and 1975 respectively. In mid-1957, Australia was involved in the International Geophysical Year (IGY) which was a global program to assess and understand the Earth’s relationship to its space environment. We should remember that Sputnik I had not launched yet then; it launched on October 4, 1957 changing humanity’s perception of space forever

The Woomara Rocket range, in South Australia, was viewed as an ideal spot to launch satellites, to include U.S. ambitions to launch the world’s first satellite. A joint Anglo-Australian project, the Woomara range was built in 1947, as a facility to study guided missile weapons development, to include testing.[12] The U.K’s Skylark Sounding Rocket program would become the longest space project in Woomara and it launched Australian, U.S., U.K., and European scientific instruments that enhanced the study of X-Ray, ultra-violet astronomy and so forth.[13] Australia’s geographic position offers it a perfect location advantage to guide and monitor rocket launches, which it continues to do so, till date. Instituted in 1958, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) established several tracking stations in Australia, earning the latter the distinction of hosting the largest number of NASA stations, outside of the U.S.[14] In my visit to Southern Australia in 2009, I was told about these installations in conversations with local aboriginal communities, who viewed these as illegal appropriations of sacred land, without any heed to their land rights.[15]

As of today, Australia is perhaps taking the right decision to establish an agency that is not solely aimed at defense assets in space, or simply developing monitoring capacities but looking at space commerce. However, missing from the ASA mission statement are any ambitions on harnessing space-based resources like Space-Based Solar Power (SBSP)[16] as well as asteroid mining. That is surprising given Australia’s focus on renewable energy resources specially to tackle issues of climate change as per their Paris Agreement commitments to reduce carbon emissions, the report on which is not flattering.[17] The ASA’s mission statement and ambitions appear too traditional and focused on satellite launches and taking advantage of the existing space commercial sector and /or regulate the civilian space sector. That said, I am hoping that Australia publishes a ‘white paper on space’ that outlines their futuristic space vision and goals, and paths that it would follow to meet those stated goals, including timelines. Consequently, whether Australian space enthusiasts, and space policy makers are truly anticipating that kind of space industrialization is not clear from the statements that I have seen so far. It appears as if the outgoing Malcolm Turnbull government set up ASA,[18] reacting to criticisms that Australia was among the only two Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, the other being Iceland, without a space agency despite its long engagement with the space enterprise.[19]

If you analyze the priorities set by the ASA, they are typical bureaucratic missions focused on old space ideas, that other nations’ space agencies have tackled decades ago. In the U.S., military space futuristic thinkers term that the Von Braunian vision of “flags, footprints and technological conquest” backed by a bureaucratic organization that is interested in space-science and setting footprints, but not committed to deep space exploration and settlement, that advocates of the O’Neillian vision articulate. A space vision, on the other hand, is “the upper limit of space development’s potential…choosing a proper vision for what future space power should achieve and how it can achieve it is far more important because it is what channels all other material support into valuable (or wasteful) action. Therefore, a critical and central component of a successful organization is its vision for the future”.[20]

The stated priorities of the ASA: “Communications technologies, services and ground stations; Space Situational Awareness (SSA) and debris monitoring; Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT) infrastructure; Earth Observation (EO) services; Research and development; Remote asset management; Developing a strategy to position Australia as an international leader in specialised space capabilities”, [21] are traditional space goals, while the discourse on space is changing rapidly from ‘getting somewhere first in space’ to establishing ability for permanent presence.

Major space powers like China are setting a different discourse on space, moving on from traditional space goals like satellite launches and space commerce and how that can benefit earth, to investing in space technology and science where the focus is on long term presence in space. China’s ‘White paper on space’ specifies China’s space goals as well as links all such activities to national development goals.[22] Significantly, Chinese President Xi Jinping articulates China’s ‘Space Dream’ within the overall ‘China Dream’, that aims to make China the strongest space faring nation by 2045 to take advantage of space industrialization (in-situ manufacturing, a lunar base and asteroid mining) that is to come in the next 20 years.[23] The fact that Xi has appointed himself President for life helps set continuity in policy and funding commitments.[24] In its lunar lander and rover mission, Chang’e 4 that aims to land on far side of the moon by the end of 2018, China will be sending a tin which will contain seeds of potato and Arabidopsis (a plant connected to cabbage and mustard), some silkworm eggs, with an aim to conduct the first biological experiment on the lunar surface.[25] The motivation behind these experiments, according to the mission chief, Liu Hanlong, is to study the process of developing food for space travelers on the lunar surface. Liu specified, “Our experiment might help accumulate knowledge for building a lunar base and long-term residence on the Moon.”[26] In a video released by the China National Space Administration (CNSA) on April 24 this year (China’s officially designated Space Day since 2016 in commemoration of its first rocket launch that same day in 1970),[27] China offered its vision of a lunar outpost to be manned by SBSP. CNSA reflected on the video that “We believe that the Chinese nation’s dream of residing in a ‘lunar palace’ will soon become a reality.”[28] In fact, four Chinese students lived in a simulated moon lab, Yuegong-1, or Lunar Palace 1, at Beihang University, for 370 days in conditions that replicated how it would be like, living on the lunar surface in a similar lab. The chief designer of Yuegong-1, Liu Hong stated that this test marked the longest stay by humans in a bioregenerative support system, where “humans, animals, plants and microorganisms co-exist in a closed environment, simulating a lunar base. Oxygen, water and food are recycled within the BLSS, creating an Earth-like environment. The system is 98 percent self-sufficient. It has been stable and effective in providing life support for its passengers.”[29] China specifies that by 2030, they will achieve their goal of a lunar base. This prospect is supported at the highest echelon of decision making with Lt Gen. Zhang Yulin, former deputy chief of the armament development department of the Central Military Commission (CMC), now with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Strategic Support Force (SSF), when he stated that “The earth-moon space will be strategically important for the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”.[30] Yulin specified that:

The future of China’s manned space program, is not a moon landing, which is quite simple, or even the manned Mars program which remains difficult, but continual exploration the earth-moon space with ever developing technology.

Based on past space accomplishments by China on similar deadlines, I estimate that China will meet their stated goal.[31] China’ space vision is about peering far ahead into the high frontiers, propelled by aspirations of permanent presence and a moon-base, something which private U.S. space companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin and Planetary Resources advocate. Taking clues from the Chinese space dream and where the discourse on space power and development is today, to include those within India,[32] another major space power, the ASA could do well to set a space vision for Australia that truly inspires the imagination of Australia’s future generations driven by far reaching ideas that envision space as a frontier of enormous potential to include harvesting resources like SBSP.

[1] “Australian Space Agency”, Australian Government, Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, at https://www.industry.gov.au/strategies-for-the-future/australian-space-agency (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

Peter Farquhar, “Australia Finally Has a Space Agency—Here’s Why Its About Time”, Business Insider, July 2, 2018 at https://www.businessinsider.com.au/australia-space-agency-value-2018-7 (Accessed on October 18, 2018).

[2] Andrew Wong, “Space Mining Could Become a Real Thing-and it Could be Worth Trillions”, CNBC, May 15, 2018 at https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/15/mining-asteroids-could-be-worth-trillions-of-dollars.html (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[3] “U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, 2015,” H.R. 2262, 114th Cong, 2015-2016 at https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2262/text (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[4] “Draft Law on the Exploration and Use of Space Resources”, Luxembourg, at https://spaceresources.public.lu/content/dam/spaceresources/news/Translation%20Of%20The%20Draft%20Law.pdf (Accessed September 17, 2018).

[5] “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”, at http://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html (Accessed September 14, 2018).

[6] “Space Foundation Report Reveals Global Space Economy at $329 Billion in 2016”, Space Foundation, August 3, 2017 at https://www.spacefoundation.org/news/space-foundation-report-reveals-global-space-economy-329-billion-2016 (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[7] “Australian Space Agency Launches Operations: A Message from Head, Dr. Megan Clark, AC”, June 29, 2018 at https://www.industry.gov.au/news-media/australian-space-agency-launches-operations-a-message-from-head-dr-megan-clark-ac (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[8] James Elton-Pym, “Budget 2018: $50m to be Earmarked for National Space Agency”, SBS News, May 3, 3018 at https://www.sbs.com.au/news/budget-2018-50m-to-be-earmarked-for-national-space-agency (Accessed on October 18, 2018).

[9] New Zealand Space Agency, Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment, at https://www.mbie.govt.nz/info-services/sectors-industries/space (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[10] Grant Bradley, “Rocket Lab Plans Rapid-Fire New Zealand Launches”, NZ Herald, August 7, 2018 at https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=12102010 (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[11] “WRESAT: Australia’s First Satellite”, Astronautical Federation, at http://www.iafastro.org/wresat-australias-first-satellite/ (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[12] Kerrie Dougherty, “Lost in Space: Australia Dwindled from Space Leader to also-ran in 50 Years”, The Conversation, September 21, 2017 at https://theconversation.com/lost-in-space-australia-dwindled-from-space-leader-to-also-ran-in-50-years-83310 (Accessed on October 18, 2018).

[13] Jonathan Armos, “Skylark: The Unsung Hero of British Space”, BBC, November 13, 2017 at https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-41945654 (Accessed on October 18, 2018).

[14] Dougherty, ““Lost in Space: Australia Dwindled from Space Leader to also-ran in 50 Years”, n. 12.

[15] Author visit to Southern Australia, July 2009. Also see Australian National Museum, Collaborating for Indigenous Rights, at http://indigenousrights.net.au/civil_rights/the_warburton_ranges_controversy,_1957/earlier_opposition_to_weapons_testing (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[16] “Space Based Solar Power”, Energy.Gov, March 6, 2014 at https://www.energy.gov/articles/space-based-solar-power (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[17] Nick Kilvert, “Forget Paris: Australia needs to Stop Pretending We’re Tackling Climate Change”, ABC News, January 10, 2018 at https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2018-01-11/record-heat-bom-paris-targets/9310996 (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[18] Michael Owen, “Malcolm Turnbull Launches Australia’s New Space Agency”, The Australian, September 26, 2017 at https://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/nation/malcolm-turnbull-launches-australias-new-space-agency/news-story/0287050c280e708a9bbefce78229afc1 (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[19] Andrew Dempster, “Lets Talk About the Space Agency in Australia’s Election Campaign”, The Conversation, June 27, 2016 at https://theconversation.com/lets-talk-about-the-space-industry-in-australias-election-campaign-61567 (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[20] Brent Ziarnick, Developing National Power in Space A Theoretical Model (Jefferson, NC: McFarland: 2005), p. 66.

[21] ASA, n.1

[22] “Full Text of White Paper on China’s Space Activities in 2016”, The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, December 28, 2016 at http://english.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2016/12/28/content_281475527159496.htm (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[23] Namrata Goswami, “Waking up to China’s Space Dream”, The Diplomat, October 15, 2018 at https://thediplomat.com/2018/10/waking-up-to-chinas-space-dream/ (Accessed on October 18, 2018).

[24] “China’s Xi Allowed to Remain ‘President for Life’ as Term Limits Removed”, BBC, March 11, 2018 at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-43361276 (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[25] “China Focus: Flowers on the Moon? China’s Chang’e-4 to Launch Lunar Spring”, Xinhuanet, April 12, 2018 at http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-04/12/c_137106440.htm (Accessed on October 18, 2018).

[26] Ibid.

[27] Echo Huang, “China lays out its Ambitions to Colonize the Moon and Build a “Lunar Palace”, Quartz, April 26, 2018, at https://qz.com/1262581/china-lays-out-its-ambitions-to-colonize-the-moon-and-build-a-lunar-palace/ (Accessed on October 18, 2018).

[28] Ibid.

[29] “China Rewrite Record, live 370 days in self-contained Moon Lab”, Xinhua, May 15, 2018 at http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-05/15/c_137180483.htm (Accessed on October 18, 2018).

[30] “Exploiting the Earth-Moon Space: China’s Ambition after Space Station”, Xinhua, July 23, 2016 at http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-03/07/c_135164574.htm (Accessed on October 18, 2018).

[31] Namrata Goswami, “China in Space: Ambitions and Possible Conflicts”, Strategic Studies Quarterly, Spring, 2018 at https://www.airuniversity.af.mil/Portals/10/SSQ/documents/Volume-12_Issue-1/Goswami.pdf (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

[32] Kate Greene, “Why India is Investing in Space”, Slate, March 17, 2017 at http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2017/03/why_india_is_investing_in_space.html (Accessed on October 19, 2018).

© Dr Namrata Goswami