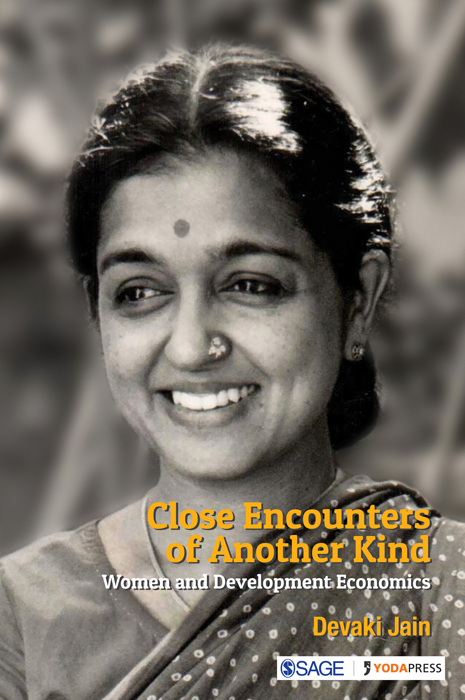

Overview of Close Encounters of Another Kind by Dr Devaki Jain

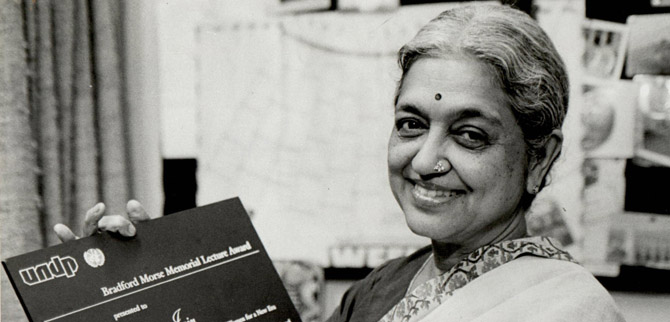

Devaki Jain, Honorary Fellow St Anne’s College, Oxford University, is Founder and former Director of the Institute of Social Studies Trust, New Delhi, India. She was previously a lecturer at the University of Delhi, a founding member of Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era (DAWN), member of the South Commission (chaired by Julius Nyerere), and of the UN eminent persons group concerned with child soldiers. She has an honorary doctorate from the University of Westville in Durban, Republic of South Africa, and has held fellowships at Harvard and Sussex Universities. She has been a member of State Planning boards and many of the Government of India’s special committees related to gender and its inclusion.

SAGE India: https://in.sagepub.com/en-in/sas/close-encounters-of-another-kind/book265741

SAGE UK: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/close-encounters-of-another-kind/book265741

SAGE US: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/close-encounters-of-another-kind/book265741

Close Encounters of Another Kind is a volume which contains lectures, research papers and policy interventions related not only to gender but also to international politics or the political milieu of the decades 1990- 2015.

Close Encounters of Another Kind is a volume which contains lectures, research papers and policy interventions related not only to gender but also to international politics or the political milieu of the decades 1990- 2015.

The papers in the book provide perspectives from the southern continents, and therefore not only define the features of these continents but also critique the application of analysis drawn from the advance economies.

The volume moves to the perspective of the developing countries on most of the economic elements- poverty, inequality, theories of growth, content of public policy. The core of the counter argument is that the characteristics of the southern continents are such that they need to design their own economic theory or a theory that is drawn from their realities.

It is suggested that globally accepted ideas on how to generate economic prosperity, namely GDP growth, have been responsible for the persistence of poverty and inequality. The logic of ‘progress’, and the idea that progress can only be capital- and profit-led, were deeply affecting the masses. It was these theories of economic growth; ideas on how to build the GDP that were responsible for poverty and inequality.

Challenging all the various given elements in development, whether it was measurement, like the number given by the official data system for female work participation in India, the factors identified as key to economic progress, the invisibilisation of women’s economic contribution- the volume moves from local and national to international theatres of policy and program formulation.

Globally pervasive ideas like globalisation and regulation are discussed and interpreted to assimilate the conditions of south countries. Descriptive categories, used to name phenomena in the south countries are also challenged for their accuracy and replaced with the more appropriate terminology.

To illustrate: A time-use study that was conducted by ISST in 1982—the earliest to be undertaken in developing countries—was basically intended to correct the figures for the work participation rate in the national statistics. The methodology used until then for counting workers had flaws. Thus, women’s actual economic contributions were not counted. The ISST study was designed such that, through observation, investigators noted what women actually did for 16 hours a day for a week in a selection of households in Rajasthan and West Bengal. This study provided many insights, especially into the fact that when you measure work according to the time spent, you not only capture what are called ‘economically valuable’ issues, but also the time that women spend serving a household—fetching water, cooking, cleaning and looking after children.

The report emerging out of this field work generated enormous amount of interest and response both by the statistical system and by activists and continues to be considered pioneering i.e. the first step towards accurate measurement of women’s work. Other field based studies such as survey of women in forest based activities reveal other kinds of measurement errors.

A study conducted of women’s role in forest based activities, revealed that what was considered a minor activity, that is gathering of forest produce like leaves berries and gums, in reality it not only added more value to local GDP, but also gives more employment to women. In this way, it was revealed that the concepts, the vocabulary and the direction of development theory were full of contradictions.

The term ‘development’ was coined basically for what were called ‘underdeveloped’ countries, or the former colonies. It was different from economic progress or economic growth. Development was supposed to include more than economic advantage. My journey in understanding, redesigning and arguing with regard to our development policy and programme had depressed me, and had shown me that in the name of development, nothing had changed for my constituency, namely women in poverty house- holds. It seemed like mere rhetoric, with no transformation. Hence my argument that while research and analysis were revealing that the design and the thrust areas of what was called ‘development’ were not making any difference, we still continued to run on the same track.

The World Bank, perhaps for the first time, prepared a comprehensive report on Gender and Poverty in India in 1991. The World Bank report was a meticulous piece of work and gave visibility and voice to less prominent areas of concern and advocacy in the women’s domain. However, I argued that while the report attempted to give a macro perspective, it remained at the micro level. It pre-empted gender advocacy from influencing macro trends. I argued essentially that the notions of an inside/outside dichotomy, access and the market, highlighted by the report, were insufficient, even inappropriate tools for moving women out of their cruel condition. If we could look not only at women’s experience of poverty, but at the ideas with which they were trying to overcome it, we might find a better way out of that terrible experience.

The women’s movement was struggling to open the eyes of policy makers and practitioners to gender differences in all areas of life—health, education, well-being, work spaces, the entire gamut of life. But not surprisingly, this knowledge was not the set of ideas that triggered policy was not a part of their consideration in the goal of removing poverty and realising a moral and equitable political economy.

The women’s movement was active on the ground, making changes, designing innovative ways in which poverty and inequality could be removed. It seemed necessary for the women’s movement to take stock of the ideas and theories behind macro-economic policy and to mobilise their voice and their creativity to change that, i.e. change the reasoning, the theory that informs the policy.

Further, it has often baffled me that there is so much awareness of the hunger and basic lack of food amongst millions of people, and that nevertheless the price of food is forbidding for those at the bottom of the economic ladder. Yet the rhetoric prevails that agriculture is a second-class citizen in the economy. As one of our senior policy makers once put it, agriculture is a ‘sunset industry’. This is in contrast to electronics, which is a ‘sunrise industry’. Some of these dilemmas or paradoxes are vividly illustrated by the case of India, with its millions of tons of food and millions of hungry people. There is a whole discourse here on how such confusion can emerge, and so using India as an illustration, this paper goes over the complexities of putting on the ground a right to food programme as mandated both by the human rights framework as well as the equitable development framework.

There has been an abiding concern with how to bring forth recognition of what is happening in the economies of the South, as well as the kinds of responses that partners and policy makers in the South countries are putting forward. While a focus on feminism had arrived on the international stage with the creation of the International Association for Feminist Economics, the preoccupation of the majority of feminist economists in such associations was with gender issues generally, with particular reference to the economies of the North.

Dramatic changes in the distribution of global economic power were vividly displayed by the outcome of the 2008 global economic crisis. While the GDP growth rates of most Northern economies were at an abysmal low, India and China blazed forward with growth rates of over 8 per cent, calling attention to the changing global economic order. These economies were named ‘emerging economies’. Their arrival on the world economic stage had huge implications for the rest of the world, and especially for women. What the data revealed was dramatic.

It was necessary for inter- national networks of feminist economists to engage with this new phenomenon, which offered a great opportunity to foreground the gender dimension in the fast-growing countries. This became particularly interesting as China was a clearly socialist economy, whereas India was still acutely a democratic polity where the playing fields were dominated by the private sector apart from the state. What were the gender implications of this difference? It would seem worthwhile not only to examine this but also to use this analysis to critique the current economic growth models.

The aim was to bring in the perspective of the developing countries on most of the economic elements- poverty, inequality, theories of growth, content of public policy. The core of the counter argument is that the characteristics of the southern continents are such that they need to design their own economic theory or a theory that is drawn from their realities.

Constantly upturning theories and propositions not only became my practice, but it also seemed the only way to move ahead. The notion that the poor needed to be enabled out of poverty through ideas that were being constructed by the benefactors haunted me. It invariably turned out to be an oppressive arrangement.

It is suggested that globally accepted ideas on how to generate economic prosperity, namely GDP growth, have been responsible for the persistence of poverty and inequality. The logic of ‘progress’, and the idea that progress can only be capital- and profit-led, were deeply affecting the masses. It was necessary for those concerned with injustice and inequality, in this case women; rebuild economic reasoning drawing from other forms of knowledge.

© Dr Devaki Jain