Is the International Criminal Court fit for purpose? by David Morgan

David Morgan has been a professional editor and journalist for over thirty years beginning his career on the subs desk of the Morning Star newspaper. He is editor of numerous historical publications under the Socialist History Society imprint. David’s interests and research include Turkey and the Kurds, literary figures like George Orwell, Edward Upward and William Morris, British anarchism, the 17th century English revolutionary era and the history of psychoanalysis. He has contributed towards many different publications and writes review articles, commentaries, opinion pieces, polemics and poetry.

The International Criminal Court forms part of the architectural of a contemporary world that has sought to learn hard lessons from its dreadful experiences of modern history marked by two world catastrophic wars, genocides, mass murder, the dropping of the atomic bomb, the use of agent orange and ethnic cleansing, to name but the worst in a catalogue of continuous barbarities.

The court stands as a counterweight, in an unfair and unequal world, to the excessive and abusive powers of authoritarian governments and faceless corporations. We live at a time of appalling atrocities and terrible war crimes in a world beset with conflicts where ethnic cleansing has become all too frequent and where women and girls are too often the most vulnerable targets of barbaric attack.

It is a world in which reckless national leaders are constantly flouting international law and where big powers armed to the teeth blunder across the planet unrestrained by every norm of decency and justice.

Nuremberg, Rwanda, Bosnia; these are some of the names that immediately spring to mind when one thinks about the international tribunals or courts that have tried to impose punishment on the perpetrators of war crimes and human rights atrocities and to provide a modicum of justice for the victims and their descendants. The very existence of such an institution possesses the potential to act as a moderating influence on those who feel they can exercise their autocratic powers with impunity. It also acts as a beacon of hope for any victims that there exists a viable means of obtaining justice in a world without mercy. In its most idealistic characterisation the ICC can be seen as an embodiment of the values of international solidarity and an arbiter of justice throughout the world shining its light on all the darkest corners of the globe where abuses of power take place far from public view.

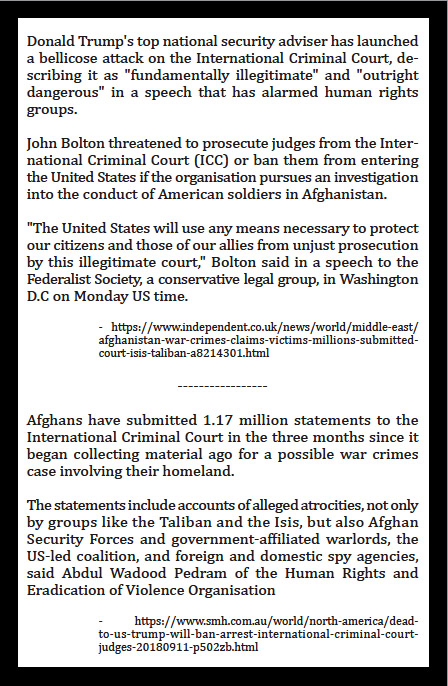

But is the ICC actually fit for purpose? Steeped in controversy since its foundation, the court has never received universal acceptance. Many of the big powers have effectively ignored it, refusing to take part or accede to its jurisdiction. It has been charged with bias, even prejudice, in its selection of cases. But it has come to public attention most recently in the light of the threats made against it by the Trump Administration after it had the temerity to investigate allegations of abuses committed by US troops in Afghanistan. These threats against it have prompted others to leap to its defence. In this heated atmosphere of polarised debate the true record and validity of the court needs to be properly analysed.

So, in attempting to draw up a non-partisan balance sheet, it is important to acknowledge the contesting views but vital to resist the temptation to take sides. The court certainly offers inadequate remedy to the enormity of the war crimes and crimes against humanity that are taking place in every continent of the world.

The vast and seemingly never ending scale of the atrocities that blight the world are more than enough to fill even the most hard-bitten cynic with despair. Just imagine residing in a country without even the semblance of an independent judiciary, where an aggrieved citizen is left bereft with no recourse to any legal mechanism to achieve a just settlement of a legitimate dispute. The law courts are part of the essential foundations of any decent, civilised society. They are absolutely necessary for the protection of the well-being of the person and of the property of a nation’s citizens.

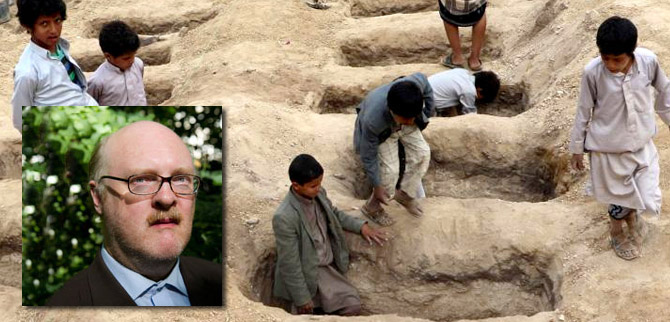

Imagine also trying to eke out a living in a war zone as many millions of the world’s population are forced to do. Daily life is a struggle for survival where one counts oneself fortunate just to get through the day unscathed. Consider if your home was ransacked by invading armies or worse still by the armed forces of your own country. How would you expect to protect your family and community in such circumstances especially if the legal system of one’s country was corrupted or non-existent?

Consider what the lives of citizens are like when the rulers of a nation abuses their power, where they routinely circumvent the law, appoint allies and family members to the bench, buy off juries or suspend legal proceedings on a whim. There are too many places where such things happen.

Imagine a multi-ethnic state where the civilised norms suddenly break down after a political or economic crisis, as occurred with the collapse of Communism in East and Central Europe or has happened in several countries in Africa and elsewhere.

In such circumstances as these and countless other scenarios, institutions such as the ICC will naturally appear like manna from heaven. This does not mean that in its practical operations the ICCC always offers an ideal remedy. But in times of extreme crisis like civil war, protracted conflict, massacres on a scale approaching genocide, recourse to the ICC may seem to offer an urgent and necessary remedy, especially when there is a complete absence of remedy within the domestic jurisdiction.

In other situations the ICC’s pursuit of a case may seem like outside interference, even meddling in one’s internal affairs by busy bodies or the illegitimate use of power. It can even be construed as a threat or an affront to national pride. A haughty nation with a proud history that believes itself to be perfect in all things, that adopts an ideology where its own institutions and methods of governance are mature and perfected to the extent that they should be emulated worldwide, is not likely at all to take kindly to being judged by an external power or to be told what to do. It cannot even conceive that it can do any wrong and will not entertain even the possibility that its citizens can be probed, tried and convicted by any international system of law. This endeavour will be deemed totally illegitimate, which explains John Bolton’s attitude to the ICC. Bolton cited US “exceptionalism”, an argument which is by no means an exceptional one because nearly all American politicians will be heard making such claims. Absurd as it is seems, they do appear to sincerely believe what they say in this respect, or at least they are sufficiently powerful to be able to compel others to accept it as a fait accompli.

The United States has, at least since the Cold War, always seen itself as the world’s leader, once the leader simply of what it termed the “free world”, but now in the age of post-Communism, it is the entire world that its remit seeks to encompass. The US is working towards “shared victories for all”, declared Mike Pompeo, Trump’s Secretary of State, at the United Nations, conveniently forgetting the repeated punch ups that US foreign policy tends to thrive on.

Pompeo’s colleague, John Bolton, President Trump’s National Security Advisor, and another very powerful person within the present American administration, sought to explain how the country’s conception of sovereignty was the reason why the US sees itself as “exceptional”. The US, Bolton said, understands sovereignty not to be vested in a head of state but within the framework of its constitution which declares that “we the people” are sovereign in America. This is a populism legitimised by reference to the country’s constitution. From this perspective any infringements on American sovereignty are infringements not on the government but on the people themselves, according to Bolton, who offered this explanation at a press conference at the UN, on 24th September. Bolton has also maintained that the legal basis for his threat to the ICC lies in the law of his country. Bolton had earlier called the court “illegitimate” and a threat to “US national security”.

The US was prompted to threaten sanctions against the court in response to news that the ICC was considering whether to prosecute American service personnel over alleged abuses in Afghanistan as part of investigations into alleged war crimes carried out during the Afghan campaign.

This current clash between the ICC and the US was initiated by the publication in 2016 of a report from the ICC which argued that there was a credible basis to claims that the US military and intelligence personnel had committed torture amounting to war crimes at secret detention centres in Afghanistan. These centres were operated by the Central Intelligence Agency.

Another development which prompted Bolton’s wrath was the attempts by Palestinian representatives to use the ICC to hold Israel to account for its human rights abuses in Gaza and the West Bank. This action was cited as a reason for the closure of the Palestinian diplomatic mission in Washington (which is the equivalent of an embassy).

The US is not the sole country that is opposed to the work of the ICC. Established by UN treaty in 2002, the ICC has only been ratified by 123 countries so far. The big powers such as China, India and Russia have joined the US in failing to ratify or give credence to the court. They will not recognise its rulings and they see its activities as illegitimate.

The court’s activities have not proved uncontroversial. It has largely been citizens of African states who have been dragged before the court which has angered African governments prompting some to threaten to withdraw from the ICC. In 2016, for instance, Gambia’s Information Minister Sheriff Bojang declared that the court existed only to “persecute and humiliate” people from the African continent. Philippine President Duterte also threatened to leave the court describing it as a “useless” tribunal.

Their declarations came in the wake of Russia’s announcement that it was formally withdrawing its signature from the ICC’s founding statute, following the court’s publication of a critical report classifying the Russian policy towards Crimea as an “occupation”. Crimea returned to Russia following a referendum of the population of Crimea who voted overwhelming to reintegrate within Russia. Western powers have insisted that the referendum was clawed and did not meet international standards.

Russian foreign ministry spokeswoman, Maria Zakharova, has said: “Russia stood at the origins of the ICC’s founding, voted for its establishment and has always cooperated with the agency. Russia hoped that the ICC will become an important factor in consolidating the rule of law and stability in international relations. Unfortunately, to our mind, this did not happen. In this regard, and in the light of the latest decision, the Russian federation will be forced to fundamentally review its attitude towards the ICC.”

The ICC is by no means uniformly supported as an institution. It can be argued that it was a product of the New World Order proclaimed by the Western powers following the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe. This collapse was seized on as an opportunity by the West to gain the upper hand and seek to impose its will on the globe. While the immediate transition from Communism to the restoration of capitalism in the USSR and the main East European states was marked by relatively little conflict and minimal casualties, this was not the case in the former Yugoslavia. A country that was formerly a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement and once held up to be a model of a devolved system of government, broke up in bloody ethnic and religious conflict whose scale and duration prompted military intervention to manage the transition and ostensibly prevent a humanitarian catastrophe. The international tribunals that followed the Balkan conflicts were forerunners to the establishment of the ICC.

The powers of the ICC are not without their controversial aspects. Its international jurisdiction is seen to infringe national sovereignty in the name of the principles of international human rights and justice. The role of the ICC has extensive powers to bring to justice people alleged to have committed crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide. It can intervene when national authorities cannot or will not take action to prosecute. It has clashed with Russia, the United Kingdom, Sudan and various other states as well as the US.

The Trump Administration’s opposition to the ICC is not a new departure for America. The US has opposed the ICC from the time that George W Bush was in the White House even though Bush’s predecessor, Bill Clinton, had agreed to formally sign the treaty in 2000 that set up the ICC. When Barack Obama became president he did not change US policy towards the ICC and never ratified the treaty, which is known as the Rome Statute. The US has expressed support for “international accountability” without ever accepting that the court’s remit should extend to US citizens. The US is content to see the ICC prosecuting foreign heads of state and governments that it regards as rivals or enemies but it has problems with the notion of universal human rights when they are extended to the US itself. It would prefer to set itself up as judge and jury of the world in these matters. Nobody should therefore be surprised that the White House views the threatened actions of the ICC against US servicemen in Afghanistan as “unjust prosecution”. Likewise, several African nations have accused the ICC of bias in singling out Africa for prosecution. The ICC is certainly a far from perfect mechanism for prosecuting human rights offenders, but it is probably doing something right to provoke the wrath of belligerent hawks such as John Bolton and various dictators from the Philippines to Rwanda.

The Trump Administration’s opposition to the ICC is not a new departure for America. The US has opposed the ICC from the time that George W Bush was in the White House even though Bush’s predecessor, Bill Clinton, had agreed to formally sign the treaty in 2000 that set up the ICC. When Barack Obama became president he did not change US policy towards the ICC and never ratified the treaty, which is known as the Rome Statute. The US has expressed support for “international accountability” without ever accepting that the court’s remit should extend to US citizens. The US is content to see the ICC prosecuting foreign heads of state and governments that it regards as rivals or enemies but it has problems with the notion of universal human rights when they are extended to the US itself. It would prefer to set itself up as judge and jury of the world in these matters. Nobody should therefore be surprised that the White House views the threatened actions of the ICC against US servicemen in Afghanistan as “unjust prosecution”. Likewise, several African nations have accused the ICC of bias in singling out Africa for prosecution. The ICC is certainly a far from perfect mechanism for prosecuting human rights offenders, but it is probably doing something right to provoke the wrath of belligerent hawks such as John Bolton and various dictators from the Philippines to Rwanda.

The US Senate has rejected an effort to end support for the Saudi-led bombing campaign in Yemen that has resulted in the deaths of thousands of civilians and driven the country to the brink of famine. “The relationship is probably the strongest it’s ever been,” Trump said. “Saudi Arabia is a very wealthy nation and they’re going to give the United States some of that wealth, hopefully, in the form of jobs, in the form of the purchase of the finest military equipment anywhere in the world.” LINK

© David Morgan