Sri Lanka’s Cannabis Problem: Roots in India by Dr Bibhu Prasad Routray, Director www.mantraya.org

Dr. Bibhu Prasad Routray served as a Deputy Director in the National Security Council Secretariat, Government of India and Director of the Institute for Conflict Management (ICM)’s Database & Documentation Centre, Guwahati, Assam. He was a Visiting Research Fellow at the South Asia programme of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore between 2010 and 2012. Routray specialises in decision-making, governance, counter-terrorism, force modernisation, intelligence reforms, foreign policy and dissent articulation issues in South and South East Asia. His writings, based on his projects and extensive field based research in Indian conflict theatres of the Northeastern states and the left-wing extremism affected areas, have appeared in a wide range of academic as well policy journals, websites and magazines. Article reprinted by special permission of www.mantraya.org.

Abstract

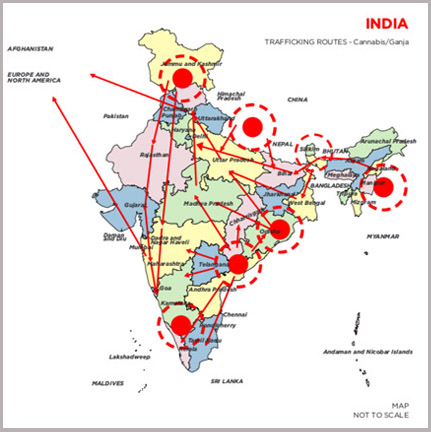

The volume of Ganja (cannabis) smuggling from India to Sri Lanka has risen significantly over the years. The demand for cannabis from Kerala in Sri Lanka has given rise to a robust supply chain that starts from states like Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Karnataka, passes through Tamil Nadu and Kerala, through the Palk Straits into the Sri Lankan waters and its landmass. The trade has grown in sophistication and is closing the divide between the licit and illicit economies. Both countries’ inability to control the illegal trade, due to logistical and capacities issues, has witnessed a trade diversification into other drugs like Hashish and Cocaine. If unchecked, a nexus between transnational drug smugglers and terrorists in the region cannot be ruled out.

On 3rdMarch 2018, Sri Lanka’s Naval Intelligence Unit received a tip off regarding movement of contraband in a luxury van from Jaffna to Colombo. A joint raid based on the information was conducted by the Special Task Force (STF) police and the Sri Lanka Navy which led to the arrest of a 51-year old suspect and recovery of 403 kilograms of Kerala Ganja (cannabis and KC hereafter) valued nearly Rupees 60 million in Telwatta, Negombo.[1] On 4 April, two persons were arrested with 220 kilograms of KC estimated to be worth around SR 25 million in Chilaw.[2]Further on 20thApril, another 150 kilograms of Kerala Cannabis were recovered from four persons in Wattala.[3]Termed as some of the biggest hauls of narcotics made in recent times, incidents like these are repeatedly demanding attention to the problem of rise of Cannabis smuggling into the country, mostly from India’s southern Kerala state.

Kerala: Route and Source

No mass cannabis cultivation takes place in Kerala, apart from the Idukki district, where it is grown privately in small scale. While the Idukki crop has fairly good demand internationally and has acquired a cult name- ‘Idukki Gold’, it is unlikely that any of this is being smuggled to Sri Lanka. Officials of Kerala’s excise department, which periodically destroys cannabis plants and arrest persons, insist that cannabis reaching Sri Lanka are from other parts of the country and could be using the KC trade name for better profit.

Such states where the drug origins are Odisha[4], Telangana[5], Andhra Pradesh[6] and Karnataka where they are illegally grown. Contraband from first three states usually travel through Tamil Nadu[7] before reaching Kerala, from where these are smuggled into Sri Lanka and Maldives. Supply from Karnataka takes a direct route as it shares a border with Kerala. Seizures of drugs from other states entering Kerala and arrests of smugglers is rather frequent indicating the large and uninhibited trade of cannabis.

In April 2018, the Narcotic Intelligence Bureau (NIB) of Crime Investigation Division (CID) seized 102 kilograms of drugs worth over INR 1 million and arrested two persons who were smuggling it to Kerala from Andhra Pradesh near Meelavittan on the Tuticorin to Tiruchendur highway.[8] In December 2017, the NIB-CID personnel in Tuticorin had seized 110 kilograms of cannabis that was smuggled from Andhra Pradesh.

Indian Customs sources indicate that while the country’s western coast was being used earlier as the smuggling route, rise in population density has made the route unviable. As a result, the eastern coast of Tamil Nadu has emerged as the new preferred route. Supply from other states are generally received at the inter-state border districts of Kerala such as Palakkad before being repacked and distributed.[9] These routes, however, keep changing. For instance, Virudhunagar which used to be the route for smuggling cannabis from Andhra Pradesh to Kerala, has given way to the route through Tuticorin. Arrests and seizures, some of which have mentioned earlier, corroborate this shift.

A new dimension indicating a change in Kerala’s profile from a mere transit state for smuggling drugs abroad to a hub of such trade has also surfaced in recent years. In the aftermath of several seizures of drugs in state capital Thiruvananathapuram, enforcement agencies indicate the state’s slide into a preferred business location for international drug cartels.

The city and its suburbs are turning into safe havens for drug trade. Among the arrested recently are three Maldivian nationals who allegedly attempted to smuggle the contraband to their country. Among seizures in 2018 (till May) are 27 kilograms of hashish oil, 200 kilograms of cannabis and synthetic drugs such as Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD).[10] Expanding clientele include local population as well as tourists. Significant quantity is smuggled abroad.

Idukki’s profile too has changed from small scale cultivation location of cannabis to a contraband processing and smuggling hub. In addition to seizure of cannabis, the Kerala Excise department is discovering that processing units that turn cannabis sourced from other states to hashish have come up in the district. A fairly elaborate network of gangs comprising inter-state agents, drug traffickers, and distributors exist in Kerala with networks outside the state for supplying cannabis to their clientele which include schools, hostels, and colleges. On occasions, drug traffickers have used school and college students as couriers. In one such incident, in January 2018, two students were arrested with two kilograms of cannabis in Kasaragod. The contraband had been sourced from Andhra Pradesh and was en route Mangalore.[11]

In Sri Lanka

For centuries, cannabis has remained an integral part of the underground as well as mainstream dope culture in Sri Lanka, like most South Asian countries. Although smoking and possessing the drug is illegal in the country, cannabis is grown in small quantities in the country since the 17thcentury and has been extensively used in traditional Ayurvedic medicines. According to the UNODC, in the beginning of the 20thcentury, Coca ‘used to be cultivated in several Asian countries including Java (Indonesia), Formosa (Taiwan) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). This largely came to a halt after World War II.[12]

While Sri Lanka legally grows small amount of cannabis for export, illegal cultivation of cannabis is limited to Eastern and Southern provinces. According to a 2003 estimate, total area of land under cannabis cultivation was 500 hectares and the estimated number of cannabis users in the country was 600,000. The quantity of cannabis seized island-wide was 73,774 kilograms and the number of cases registered in 2003 was 9,556, of which three percent involved women.[13] In July 2013, authorities discovered cannabis plantation in Yala National Park in Uva and Southern Provinces. The plantation was not only large, but also was remarkably well-equipped, with solar cells, solar-powered irrigation systems and supplementary lighting.[14] Since 2002, however, the character of the problem has changed with a diversification in the drugs supply. Sri Lanka today lies in the transit route of drugs like heroin and cocaine, passing through the country to Africa. In 2016, a total of 36817 kilograms of cannabis, which is mostly for internal consumption, were recovered in Sri Lanka.

For some reason, the relatively expensive KC, in addition to the drug smuggled from Pakistan and Afghanistan, has caught the imagination of the Sri Lankan dopers. Compared to a tola(ten grams) of local cannabis that cost around SR 4000 (approximately US$25 at the prevailing rate of US$1=SR158), a tola of KC costs around SR 12000 to 15000 in Colombo. The users include the locals as well as the tourists. This rising demand is feeding the export market in India. In 2002, India’s Narcotics Control Bureau reported that seizures in the Indo-Sri Lankan sector rose from a mere 38 kilograms (6 percent of total Indian seizures) during 1998 to 350 kilograms (37 percent of total Indian seizures) during 2002. Since then the trade volume has risen significantly.

On 30 May 2018, two persons were arrested while transporting 24 kilograms of KC in Mannar. The seized contraband was valued at SR 2.9 million.[15] Less than two weeks later, eight kilograms of KC was recovered from a 51-year old man travelling in a Sri Lanka Transport Board (SLTB) bus plying to Colombo, at Puliyankulam in Vavuniya.[16] Such incidents suggest that the drug typically originates from the country’s north from where these are transported in luxury vans, three wheelers, and public transportation vehicles as well as motorbikes, depending on the volume and risks involved.

The role of the Indian smugglers involves delivering the contraband to their Sri Lankan counterparts on high sea via the Palk straits using small country crafts, which on odd occasions venture into Sri Lankan waters. However, distance of such incursions is kept to the minimum to allow smugglers time to return into Indian waters when challenged by the Sri Lanka Navy. Abandoned boats with KC packets have been periodically seized. Sacks filled with KC, buried on beaches like Kalpitiya on the Uchchimuniya Island, have been recovered.[17] KC packs floating in the Valvettithurai seas too have been recovered. Sri Lanka police sources indicate that 31 Indians were arrested for drug offences in Sri Lanka in 2016 and 2017. The first five months of 2018 have already witnessed arrest of seven Indian nationals.[18]

There are reasons to believe that cannabis smuggling has begun to transcend boundaries that divide the licit and illicit economies. People involved in the smuggling range from teenagers, older persons, and also some of the influential businessmen and politicians in Sri Lanka. Owner of the famous Jetwing hotel in Jaffna as well as a leading Private luxury bus owner from Jaffna were allegedly involved in the smuggling of KC to the South, in big quantities. In May 2018, in spite of public outrage, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe did not cancel his official dinner in the Jetwing hotel in May 2018, which led to an incident of stone pelting targeting the hotel.[19]

Conclusion

Till 2010, Sri Lanka had limited interdiction capacity along its lengthy 1340 kilometres-long coastline since it did not have coastguard to guard its maritime zones and territorial waters. Even after the Coastguard was re-established and started operating, its capacities remain insufficient to control the rise of cannabis smuggling from India, thereby burdening the Sri Lanka Navy with the responsibility. India’s NCB and Sri Lanka’s Police Narcotics Bureau have a bilateral mechanism to cooperate in this regard and in May 2018 entered into an understanding to cooperate and exchange information to tackle smuggling of drugs in both countries.

However, the NCB itself suffers from a range of deficiencies including drastic shortage of manpower and coordination issues with the state police forces. Multiple agencies’ inability to coordinate their actions and work on a common agenda continues to be the crux of the problem. Isolated arrests and recoveries notwithstanding, smuggling of cannabis finding their way from India to Sri Lanka will continue unabated till these logistical and capacities issues are addressed. If unchecked, a nexus between transnational drug smugglers and terrorists is not difficult to foresee.

End Notes

[1]“Sri Lanka Navy, STF seize over 400 kg of Kerala ganja in Negombo”, Colombo Page, 3 March 2018, http://www.colombopage.com/archive_18A/Mar03_1520098356CH.php. Accessed on 24 June 2018.

[2]“Two arrested in Chilaw with 220 kilograms of Kerala Ganja”, Sunday Leader, 5 April 2018, http://www.thesundayleader.lk/2018/04/05/two-arrested-in-chilaw-with-220-kilograms-of-kerala-ganja/. Accessed on 23 June 2018.

[3]“Four arrested with Kerala Ganja and hash in Wattala”, Sunday Leader, 20 April 2018, http://www.thesundayleader.lk/2018/04/21/four-arrested-with-kerala-ganja-and-hash-in-wattala/. Accessed on 25 June 2018.

[4]Pockets of Angul, Deogarh, Sambalpur, Gajapati, Kandhamal, Rayagada, Malkangiri and Boudh districts have traditionally grown cannabis. Although the Odisha police blame for the left-wing extremists for the illegal activity, very little evidence exists to link the extremists with the trade.

[5]Hundreds of acres of land in Adilabad, Nirmal, Asifabad, Sangareddy, Jogulamba Gadwal, and Manchiryal districts are used for illegal cannabis cultivation in Telangana. Reports indicate smugglers from Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Hyderabad are supplying seeds free of cost to the farmers to lure them into this. Farmers cultivate the crop in between other crops with similar leaves like cotton, chillies, subabul (Leucaena leucocephala) and marigold. ‘Telangana: Free seeds, high returns, lure farmers to grow drug’, Deccan Chronicle, 10 March 2017, https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/current-affairs/100317/free-seeds-high-returns-lure-farmers-to-grow-drug.html. Accessed on 04 July 2018.

[6]According to estimate by Advanced Data Processing Research Institute (ADPRI), which uses satellite data imagery, cannabis is grown in 10,000 square kilometres of Andhra Pradesh, especially in Visakhapatnam and East Godavari districts.

[7]Officials maintain eastern coast of Tamil Nadu rather than the thickly populated western coast is a safer route for smugglers.

[8]M K Ananth, “102 kg ganja transported from Andhra Pradesh to Kerala seized in Tuticorin”, Times of India, 15 April 2018, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/102-kg-ganja-transported-from-andhra-pradesh-to-kerala-seized-in-tuticorin/articleshow/63769975.cms. Accessed on 26 June 2018.

[9]“Major ganja haul in Idukki”, The Hindu, 9 May 2014, http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/major-ganja-haul-in-idukki/article5992645.ece. Accessed on 23 June 2018.

[10]Sarath Babu George, “Drug seizures trigger alarm”, The Hindu, 23 June 2018, http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-kerala/drug-seizures-trigger-alarm/article24237435.ece. Accessed on 23 June 2018.

[11]“2 students held with 2 kg of ganja”, The Hindu, 18 January 2018, http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/2-students-held-with-2-kg-of-ganja/article22466758.ece. Accessed on 23 June 2018.

[12]A Century of International Drug Control, UNODC, 2009, p.84, http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Studies/100_Years_of_Drug_Control.pdf. Accessed on 04 July 2018.

[13]UNODC, 2005, https://www.unodc.org/pdf/india/publications/south_Asia_Regional_Profile_Sept_2005/13_srilanka.pdf. Accessed on 04 July 2018.

[14]‘Massive ganja plantation inside Yala National Park’, Daily News, 11 July 2013, http://www.dailynews.lk/2013/07/11/local/massive-ganja-plantation-inside-yala-national-park. Accessed on 04 July 2018.

[15]“Sri Lanka Police arrest two with 24 kilograms of Kerala cannabis”, Colombo Page, 30 May 2018, http://www.colombopage.com/archive_18A/May30_1527663992CH.php. Accessed on 25 June 2018.

[16]“Police arrest man transporting 8 kg of Kerala Cannabis in public bus”, Colombo Page, 11 June 2018, http://www.colombopage.com/archive_18A/Jun11_1528695474CH.php. Accessed on 25 June 2018.

[17]“Three sacks of Kerala Ganja found on Kalpitiya beach”, News First, 7 October 2017, https://www.newsfirst.lk/2017/10/police-seize-81kg-kerala-ganja-found-buried-beach/. Accessed 24 June 2018.

[18]Sri Lanka Police sources.

[19]“Stones Pelted On The Hotel Where Ranil Had Dinner”, Asian Tribune, 29 May 2018, http://asiantribune.com/node/91894. Accessed on 2 June 2018.

© Dr Bibhu Prasad Routray/Mantraya