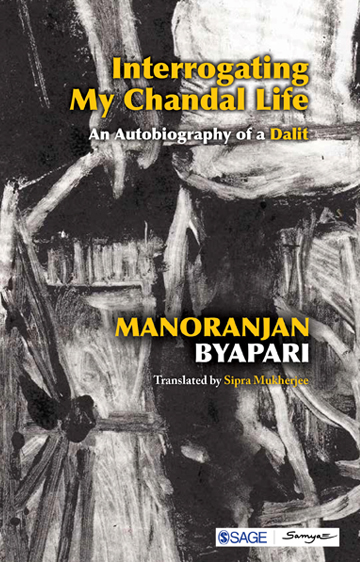

Interrogating My Chandal Life, An Autobiography of a Dalit by Manoranjan Byapari. Translated by Professor Sipra Mukherjee.

Manoranjan Byapari has worked at many kinds of jobs and also been writer-in residence at Alumnus Software, Calcutta. He never went to school or university. He is a popular writer in the literary magazines and in 2014 received the Suprabha Majumdar prize awarded by the Paschimbanga Bangla Akademi. He was awarded the 24 Ghanta Ananya Samman in 2013. He and his writings are well known as he speaks about Dalit issues in Hindi, becoming proficient in the language while he was with the Mukti Morcha of the late Shankar Guha Neogi in Chhattisgarh.

Translator Sipra Mukherjee is Professor, Department of English, West Bengal State University. Her research interests are religion, caste and power. Her interest in literatures of the margins began with research into early missionary journals of Northeast India. She has since worked on small religious sects and is presently trying to archive the local cultures of North 24-Parganas at her university. She has published with Brill, Oxford University Press, McGill-Queen’s University Press, SAGE, Sahitya Akademi, Ravi Dayal, Routledge and Permanent Black.

SAGE India: https://in.sagepub.com/en-in/sas/interrogating-my-chandal-life/book262370

SAGE UK: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/interrogating-my-chandal-life/book262370

SAGE US: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/interrogating-my-chandal-life/book262370

Manoranjan Byapari – My experience of this book

Manoranjan Byapari – My experience of this book

(Translated from Bangla by Sipra Mukherjee)

J for jail.

J for Jijibisha.

J for Jivan.

At the same time, J is for ‘jiddi’ (ziddi= stubborn)

J is for ‘jung’ which means battle in Hindi.

J is also for Jai, that is victory.

Much in this way, my autobiography spans a wide range from the miseries of the jail to the thrill of a ‘jai’.

Chandal refers to an untouchable caste, but at the same time, the word ‘chandal’ in Bangla is also an adjective used for a man who is filled with fury. The person who this book deals with is one who is both. Victim of the Partition of India, he begins his life as a goatherd. At the age when others go to school with books and pencils, he tended the goats and cows with a stick in hand. And then, shivering with cold, washing glasses and cups at a small shanty tea shop. When a little older, he worked as a coolie, as a rickshaw-wallah, driven by hunger snatching bread from the jaws of a dog. And then at a later stage, running through the streets of the city with a knife or a bomb in hand. – Such a life usually ends as a corpse spread out on the post-mortem table, or else in the darkness of the dungeon. It is such a man who tells his story in this book. The story can thus be described as the story of a man who was not supposed to have lived this long. A man who has clung to life with all his limbs in an octopus-like embrace, struggling to live in the hostile environment of poverty, starvation, exploitation, oppression. In the prison at the age of 24, learning the alphabet by etching the letters on the earthen floor of the prison house, and from there to University of Hyderabad, to Delhi University, to West Bengal State University, to Presidency University, to the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, the Paschim Banga Sahitya Sansad, Jawaharlal Nehru University, and then to Jaipur Literary Festival. This book tells the tale of my struggle, from my boyhood to the publication of my first book. I had sat myself down on the field at the Calcutta Book Fair and sold my books. How is this any less of an achievement than the climber who ascends Mount Everest sans all life-support? It is unlikely that this book will help my readers with their examinations or interviews. But it may just help them to turn around and fight the injustices and despairs of life. I have indeed been fortunate to have readers who have said as much when they met me: “You gave me the courage to go ahead, to not succumb and commit suicide. If you could live despite such agony, then perhaps I can too.”

I do not know what the aesthetic or artistic value of my work is, but I do believe that if my writing can give strength to those who are weak and downtrodden, then my book is successful. I have been writing since 1980 and so have been writing for the past 30 to 38 years. I have published about 12 or 13 books, and have written much for journals. Many manuscripts lie with me, incomplete. Yet I am hesitant to call myself a writer. I would rather call myself a person who has kept continuously writing, persistent ‘lekha’, to become a ‘lekhowar’, like those who practise their games persistently to emerge after the incessant ‘khela’ as ‘khelowars’. I have raised my voice against oppression and injustice, against the arbitrary persecution of the poor and the weak. I believe myself to be a representative of resistant humanity.

It is for them that I write. It is on their side that I am. When I take up my pen it is for them and for their rights. For them I will write, I will join the michhils, I will shout. I do not believe in caste, religion, colour, sect. I know that there are only two kinds of human beings on this earth: good and bad, the oppressor and the oppressed, the dalak, the one who oppresses, and the dalit, the one who is oppressed. My life is dedicated to the latter of these. I have no weapon but my pen, and that too a cheap one, but I will fight as long as I can wield it. This promise marks every page of my book, Interrogating My Chandal Life

Professor Sipra Mukherjee – Translating Byapari’s Chandal Life

Translating Manoranjan Byapari’s book has been quite an experience. As a reader and translator, one moves from the agony of a young boy, haunted by hunger, to the thrill of a tipsy Manoranjan, impatient and irritated in Bastar, snatching the microphone from a political leader, to script a ‘proper’ speech for him. It is a tale that moves between the urban and the rural space, taking you through lows that are dark in their unplumbed depths, to unexpected highs that speak of the grit of the human spirit and the generosity of human nature.

Moving from East Pakistan just after the chaotic Partition, to the refugee camps in West Bengal, through the Food Riots, to the margins of the city of Kolkata still reeling from the impact of the bloody Partition and the influx of thousands of refugees, this is a story of Bengal that has remained largely untold. This statement may come as a surprise since Bengal and the city of (then) Calcutta are both subjects that have had tomes of works written on them. Yet this book, set in close proximity to the history of the mainstream: Partition, Communism, Naxalite movement, – narrates a story that amazes and shocks. It is for this reason that Binayak Sen said that “this incomplete history, which had for long assumed the partial to be the whole, the sectional to be the national, is sought to be completed through Manoranjan’s pen.”

Possibly the one experience that dominates the life of the boy Manoranjan who runs away from home, terrified by the prospect of facing daily hunger – is one of just that which he sought to escape: hunger. Hunger is the one persistent certainty that dogs his footsteps. The slightly older teenager with him who, like Manoranjan, lives off the streets, expresses surprise that Manoranjan neither smokes nor drinks. “So, what is your vice?” he asks Manoranjan. “Rice,” answers Manoranjan after pausing to think, “Rice is my vice”.

One feature of the language that made translation into the language of English simpler is the ‘universality’ of the language that Byapari uses. Rootless from birth, his language is only minimally rooted in the specificities of one urban or one rural locale. Moreover, this is the story of a desperate man, who is exploited, is pushed to the edge repeatedly, and who learns early that offence is the best defence. In circumstances such as these, language can be largely bare and unadorned:

There was a broken bit of a brick lying on the ground before me. Without stopping to think and with the speed of lightning, I picked it up and, gathering all my body’s strength in my two arms, thrust the brick into the forehead of the boy with the knife. I aimed for the centre of the forehead, a spot which, if struck with force, usually kills. The knife fell out of his hand as he dropped to the ground with a groan. I pounced upon the Kanpuri and, with it in my hands, turned round at the remaining two.

‘Come, who is it now!’

But they did not come. They ran away, into the darkness, leaving their moaning friend on the ground.

This is not to say that there is no sentimentality, a feeling difficult to put aside when one is recounting incidents in one’s own life when one was helpless and victimized. But Byapari steers his way through this expertly by distancing himself, the writer, from his younger self, by naming that youth Jeeban, preyed upon by one wolf then another, and therefore making it a third-person narrative in these places.

Translating this book did not come with the usual difficulties that are recounted by translators of dalit prose. The language was not ‘different’, the words and terms used were not of another reality and unknown to me, an upper caste mainstream-educated translator. But in all likelihood, this is how many of the modern dalit narratives are going to be, with the earlier ‘differences’ between the Dalit and Upper-Caste literatures fading. With hunger, poverty and violence exploding the earlier comfortable distances between classes and castes, the erstwhile separation of narratives that had characterized earlier literatures will in all likelihood minimize. West Bengal may just be one of the provinces where this is easier to catch, with the Partition causing many to flee the more agrarian East Bengal into India.

© Manoranjan Byapari and Sipra Mukherjee