Unpacking the History of Sabich by Jennifer Shutek

Jennifer Shutek is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Nutrition and Food Studies at New York University, Steinhardt, where she is pursuing research projects on several interwoven topics, including: the social functions of generosity among West Bank Palestinians, the semiotics of agricultural images in Zionist and Palestinian propaganda, the entangled histories of sabich and Arab-Jewish migrations to Palestine/Israel, and gastrodiplomacy in Palestine/Israel and among diasporic Palestinian and Israeli communities in North America. She obtained her BA in Middle Eastern and Islamic History with a minor in English literature at Simon Fraser University and her Master of Philosophy in Modern Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Oxford. Her master’s thesis analyzed narratives of gastronationalism and culinary diplomacy in Palestinian and Israeli cookbooks. She will be returning to Israel in the spring of 2018 as part of NYU’s Provost’s Global Research Initiative program to carry out fieldwork on gastrodiplomacy, food in the arts, and food preparation and consumption during Jewish holidays. Twitter: @quixoticavocado

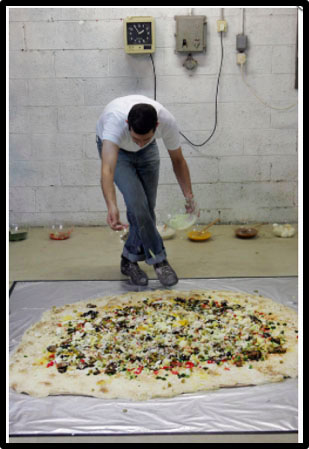

The scene opens on a man wearing a white T-shirt, faded blue jeans, and lace-up sneakers covered in what appear to be splotches of white paint. He stands with his back against a white painted-brick wall. On his left sit clear glass bowls filled with various ingredients: cucumber pickles; shiny, peeled hard boiled eggs; vibrant chopped salad; thick chunks of charred purple aubergine; turmeric-yellow ‘amba. Each bowl contains a long-handled wooden spoon. He begins by reaching for the bowl of tahina; the frame widens, revealing a massive pita sitting atop a silver drop cloth; the artist uses a wooden spoon to drip the tahina across the pita’s surface. He continues, Pollock-like, to walk around his pita-cum-canvas, drip-painting with all of the ingredients – flicking ‘amba, using his hands to crush and crumble the eggs, scattering chopped salad – until the pita is covered with thick layers of the ingredients for the widely consumed Israeli street food: sabich.

This short film, the work of the internationally acclaimed Israeli performance and film artist Shahar Marcus, speaks both to his past (as a child, Marcus would sometimes breakfast with a neighbouring family of Iraqi Jews, sharing a plate of tahini, ‘amba, small pitas, eggplant, and hard boiled eggs) and to the current Israeli food scene. The proliferation of small kiosks selling sabich alongside falafel and shwarma, the appearance of destination sabich vendors such as Sabich Oved in Giv’atayim, and the publication of numerous articles on sabich in the last two and a half decades attest to sabich’s place of prominence the Israeli culinary landscape. However, despite its widespread consumption, sabich’s history is rarely examined in depth.

Food writers and cookbooks authors agree that sabich began as an Iraqi Jewish Shabbat food, detailing how the standard ingredients of fried aubergine, hard-boiled egg, chopped salad, tahina, and ‘amba (a South Asian pickled mango sauce) were prepared on Friday and left out overnight in accordance with Shabbat requirements. Brought to Israel in the 1950s during the mass migration of Middle Eastern Jews (Mizrahim), these ingredients were later put into a pita to create the now-familiar sabich sandwich. Articles in Haaretz, Tablet Mag, and Saveur, for instance, state that the idea of putting the ingredients into a portable pita was “100 percent Israeli.”[1] These texts often cite the popularity of sabich and other “Middle Eastern” or “Arab” foods as indicative of multiculturalism in Israel, suggesting that the existence of a cosmopolitan foodscape reflects Israel’s diversity and inclusivity. The rise of sabich reflects the popularity of Arab-Jewish (Mizrahi) foods more generally. Indeed, the number of Arab restaurants in Israel’s two largest cities, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, exceeds all other types of eateries except for Italian.[2] However, the development of a culinary scene favouring Mizrahi foodways occurred over several decades, within a state that historically privileged European Jews (Ashkenazim) over Jewish immigrants from Middle Eastern and North African countries.[3] Ashkenazim, culturally and politically dominant during the period of the British Mandate in Palestine and the early years of the Israeli state, slowly and selectively adopted cultural aspects of marginalized groups (especially Palestinians and Mizrahim), and often-overlooked histories of ethnic divisions, class tensions, and traumatic migrations that lie behind the sabich sandwich.

While culinary exchange and fusion have been taking place for centuries, these have rarely been neutral processes. They have typically occurred within power imbalances framed by conquest, colonization and appropriation. Although cooking dishes from various parts of the world is not an inherently neo-colonialist act, the whole-sale use and labeling of the foodways of one group as those of another can, in fact, participate in appropriation and cultural erasure. Consuming a food or dish without falling into culinary appropriation requires a nuanced understanding of its history and the matrices of power in which it is produced. While a discussion of some of the history behind the current status of sabich as a “totem” or archetypal Israeli food in and of itself will not transform painful histories into palatable ones, it can support increased understanding of and sensitivity toward the histories and power dynamics that shape contemporary Israeli culinary culture.

Iraqi Immigration to Israel

Because sabich originated from Israel’s Iraqi Jewish community, narrating its history requires an understanding of Iraqi immigration. The history of Operation Ezra and Nehemiah (the transportation of most of Iraq’s Jews to Israel from 1951 to 1952) contextualizes sabich’s introduction; its contemporary popularity is rooted in this history.[4] Several concurrent and mutually intensifying factors, including Zionist propaganda, the memory of the farhoud (a wave of unprecedented violence against Iraqi Jews in 1941), governmental instability in Iraq, and the efforts of the Israeli government to transport Iraqi-Jews to Israel facilitated the emigration of approximately 120 000 of Iraq’s 130 000 Jews to Israel between 1950 and 1952.[5] Resulting from negotiations between Israeli representatives in Iraq and the Iraqi Prime Minister and by the Near East Air Transport and El Al (Israel’s national airline), Operation Ezra and Nehemiah was one of the largest migrations in this period of Israeli history.

The Israeli press portrayed Operation Ezra and Nehemiah as a rescue mission, saving Arab-Jews from oppressive Arab regimes. However, many members of Israel’s political elite articulated a belief that Arab-Jews constituted a backward, uncivilized population. Abba Ebban, an Israeli politician, scholar, and Minister of Foreign Affairs, for example, voiced his concern that “the predominance of immigrants of Oriental origin force Israel to equalize its cultural level with that of the neighboring world”; Golda Meir asked whether or not the Israeli state could “elevate these immigrants to a suitable level of civilization.”[6]

This mission civilisatrice manifested in initiatives to educate and discipline the minds and bodies of new immigrants through sanitation, personal hygiene, child care, and diet. Doctors, nurses, and journalists frequently depicted Mizrahim as backward and unhygienic in their rejection of western medicine during the period of the British Mandate in Palestine and early years of the Israeli state.[7] Motherhood guidebooks were produced, aimed at rectifying the “backward” diet and hygiene of Mizrahim and contrasting the good Israeli mother with the deficient Arab-Jewish immigrant mother. After arriving in Israel, many Arab-Jews were kept, sometimes for months, in ma’abarot (transit camps) where they received food provisions from the state.[8] While providing sufficient calories, provisions often consisted of unfamiliar foods, and familiar foods cost significantly more.[9] For instance, while margarine was abundant, oil, a fat more common within Arab communities, was expensive, and Mizrahi immigrants (including those from Iraq) sometimes sold eggs on the black market to obtain money to purchase oil.

The criticisms of Mizrahi consumption patterns, hygiene, and eating habits began to change at the end of the 1950s. In 1958, a report produced by the Israel Institute of Applied Social Research and the Department of Preventive Medicine at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Hadassah medical School recommended serving Middle Eastern dishes in schools to preserve immigrant foodways and to increase the prestige of Middle Eastern food, in part because it was seen to be more suitable to the Israeli climate. Ofra Tene, a scholar of Israeli food, notes that consumption of Mizrahi food also increased with the incorporation of Mizrahi food into the Israeli army’s menus.

The Future of Sabich

A 2017 children’s book by creative writing teacher at the University of Haifa and children’s writer Tami Shem-Tov, provides an alternative engagement with sabich, one that addresses its difficult history. “Sabba Sabich,” or “Grandpa Sabich,” narrates the origins of sabich in Israel through the story of Iraqi-Jewish immigration. In a December 2017 Haaretz article, Professor of Literature at Tel Aviv University Yahil Zaban notes the significance this book, which deals with ethnicity, immigration, and the appropriation and erasure of Mizrahi identity.[10] While the publication of the book is still too recent to assess its impacts, Zaban indicates that it has enjoyed high sales. Sifriyat Pijama, a reading and literacy program that operates in conjunction with the Israeli Ministry of Education to foster reading-readiness among Jewish Israeli students, created a lesson plan for “Sabba Sabich” which includes a guide for parents with post-reading discussion questions such as “did you know where the name Sabich originated before reading this story?” and “Sabba Sabich came to Israel from Iraq. Where did your family come from?”

Although it is an optimistic perspective, “Sabba Sabich” helps to imagine how food might enable difficult but essential discussions about larger issues of immigration and ethnicity in Israel. Discussions of sabich that seek to understand its origins and the complex history of Iraqi Jewish immigration to and marginalization within Israel can facilitate a mindful culinary and cultural fusion. Foods like sabich thus become vehicles for discussions about topics including power dynamics, ethnicity, and state-based discrimination, demonstrating the potential for food preparation and eating to increase awareness and cross-cultural empathy.

[1] Aimee Amiga and Liz Steinberg, “How to Make Sabich, an ‘Israeli Sandwich’: Recipe and

Video,” Haaretz, March 24, 2016; Dana Kessler, “Tel Aviv’s ‘Pita Nazi,’” Tablet Mag, November 15, 2012.

[2] Nir Avieli, Food and Power: A Culinary Ethnography of Israel (California: University of California Press, 2017), 82-83.

[3] The historical development of an ethno-racially hierarchical Israeli state is beyond the purview of this article; numerous scholars have addressed this, including Aziza Khazzoom, Ella Shohat, Dafna Hirsch, Sammy Smooha, and Oren Yiftachael.

[4] Orit Rozin, “Food, Identity, and Nation-Building in Israel’s Formative Years,” Israel Studies Forum 21.1 (summer 2006), 52-53; Nadav Davidovich and Shifra Shvarts, “Health and Hegemony: Preventive Medicine, Immigrants and the Israeli Melting Pot,” Israel Studies 9.2 (Summer 2004), 173.

[5] Michael Laskier, “The Emigration of the Jews from the Arab World,” in A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations edited by Abdelwahab Meddeb and Benjamin Stora (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2013), 428.

[6] Quoted in Ella Shohat, “Sephardim in Israel: Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Jewish Victims,” Social Text 19/20 (Autumn 1988),4-5.

[7] Hirsch, “‘We Are Here to Bring the West,’” 587-588.

[8] Shohat, 12.

[9] Orit Rozin, paper presented at “Israeli Cuisine” conference at American University in Washington, D.C., November 13, 2017; Shohat, 22, talks about governmental subsidies for European-style bread but not for pita, the latter eaten by Arab-Jews and Palestinians.

[10] Yahil Zaban, cited in Ronit Vered, “The Story behind an Iconic Israeli Street Food: The Sabich,” Haaretz, December 21, 2017.

© Jennifer Shutek