A Photographer’s India by Miriam Isabelle Cherribi

Miriam Isabelle Cherribi was born in 1998 in Amsterdam and lived in the historic city center for five years before moving to Atlanta where she is currently a freshman at Emory University. She also lived in Mumbai in 2013 and was a student at the American School of Bombay. She has visited museums, memorials, and historic sites in many countries in Europe and Asia, as well as Morocco, Argentina and Chile. Miriam speaks French and Dutch. She enjoys illustration, painting, design, photography and martial arts.

Photograph of cows by Mark Ulyseas.

Photography can be described in so many ways. Photography is defined as “the science, art, application and practice of creating durable images by recording light…either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film.” [1] While this definition may be technically correct, photography is more than just the scientific and physical aspects of the camera and image creation. Photography also evokes a mental aspect of various emotions. Photography can be an emotional experience not only for the viewer of the photograph but also for the photographer. Photography is a powerful medium to transport the viewer into thinking about unfamiliar cultures, locations, and subjects.

When I lived in India with my family in the last half of 2013 as a first-year high school student at the American School of Bombay, my younger sister and I would be driven to school very early in the morning on days when we had sports team practice. On those mornings when I was not still sleeping in the car, I would observe many people living in slums along the side of the highway or under bridges, in shantytowns away from the larger and more wealthy areas of Mumbai. I vividly remember the little naked toddlers playing by the side of the road, and the smiling toothless beggars dressed in mismatched clothes. The colors I saw on the streets of India stood out.. India’s colors can evoke many emotions. I can still hear the honking and yelling as people try crossing the busy streets. The distinctive sometimes sweet smell of the air in Mumbai has become part of the images I recall.

India is one large frame with millions of subjects each of them unique and each with an individual story. In that sense, India is like everywhere. Though many of the specific images I remember from India may seem a bit depressing, there is a feeling of happiness in the country that made me see beyond the sadness and poverty that we find in many societies around the world.

Despite all the cars honking, the child beggars sent to trick one into giving them money for gangs, the cows and sometimes even elephants walking the streets, there remains a profound sense of serenity. It is a sense of serenity that stems from India’s ancient civilization and contemporary spirituality.

In this article, I discuss three photographers whose work on India I find especially moving: Henri Cartier-Bresson, Mary Ellen Mark, and Craig Semetko.

One of the greatest photographers of our time shot in black and white only. Henri Cartier-Bresson’s moving work has inspired generations. MagnumPhotos.com exhibits Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs from “India 1947-1948,” a number of these also can be found in his book The Decisive Moment, published in 1953.

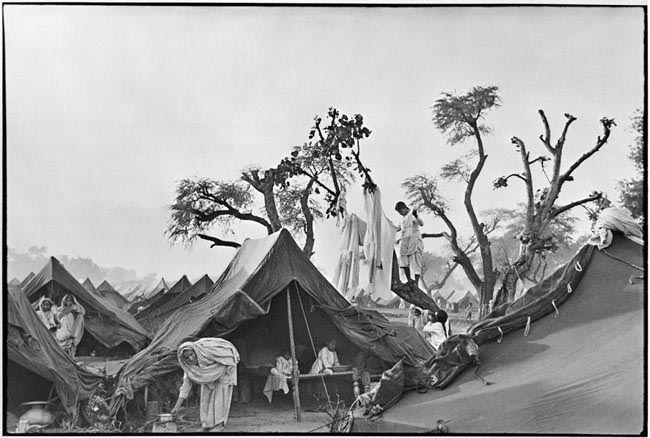

It is difficult to think of a more decisive moment than 1947-48 to be a photographer in India. Cartier-Bresson experienced India immediately after Independence from the British Raj on August 15, 1947 and during violence of the Partition, when thousands of families were brutally murdered while moving across the new borders between India and Pakistan. One surreal monochrome image titled “INDIA. Punjab. Kurukshetra. A refugee camp for 300,000 people. Autumn 1947,” depicts a seemingly endless sea of tents, with laborers, women working, and children resting, in the blistering Indian sun.[2] With this photograph, Cartier-Bresson reminds us of the shared culture torn apart by the violent Partition. His work at this time of great upheaval in India evokes feelings of empathy and compassion from the viewer.

Cartier-Bresson was not one to mince words, especially when it came to photography. During a brief encounter with American William Eggleston, a pioneer of color photography, the Frenchman commented “You know, William, color is bullshit.” [3] The same sentiment was aired differently by Ted Grant, a Canadian photojournalist, when he said, “When you photograph people in color, you photograph their clothes. But when you photograph people in black and white, you photograph their souls!” [4]

Mary Ellen Mark, a legendary American photographer, made many trips to India over the course of her lifetime. She published several books from her India projects including the colorful Falkland Road: Prostitutes of Bombay in 1981, Photographs of Mother Teresa’s Missions of Charity in Calcutta, India in 1985, and Indian Circus in 1993.

Her first book from India is one of my favorites. Falkland Road: Prostitutes of Bombay exposes an unseen lifestyle of individuals in Mumbai, one that I never knew about nor wanted to know about until I saw this book. These images are raw and powerful. They showcase what can be hard to look at but shed light on a subculture that it usually overlooked within Indian society. My favorite image from this book is of teenage girls staring. Two girls facing the camera are standing, a third girl is seat and we see her profile. The girls look to be between the ages of 12 and 15, probably forced into prostitution. We see the back of a man who is appears to be about to choose one of them.The intense looks on their faces reveal their daily struggle. The dark reds in this image and the lighting at night give a dangerous feeling about the situation. The colors and lighting enhance the feeling the discontent and apprehension one observes in the faces of that these girls.[5]

When looking at the faces of the subjects in Mark’s photos, their emotions clearly tell a story. Mark is able to step inside a hidden world and expose it to society. Shooting in color and in black and white, Mark creates a story through her images that are often shocking and always truthful in revealing the real struggles faced by many individuals. Commenting on Mark’s work in Falkland Road: Prostitutes of Bombay, blogger Jenny McPhee writes: “The portrayal of a subject’s nakedness, real or metaphoric, arouses our horror, desire, pity, mirth, joy, and, at its most successful, inspires self-reflection and empathy.”[6]

It would be difficult even for Ted Grant to disagree that, in this case, shooting in color in 1978-79, Mark’s photograph indeed captures the souls of these girls. Mark spent ten years thinking about the project after first visiting Falkland Road in the late 1960s. In the Afterword to her book at her website, she explains how the project could not have been made today and even then it was difficult.[7] Because of the subject matter no American magazine would publish it. Although Geo magazine sent her to India for three months to shoot Falkland Road, on what was one of her many visits there and elsewhere in the country, Geo passed the story to her sister magazine, Germany’s Stern, which ran many of the photographs over 13 pages. Reading the Afterword, we recognize that the Falkland Road project was the most moving experiences Mark ever had during her career as a photographer.

Craig Semetko is a contemporary photographer who is inspired by the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Elliot Erwitt, and Mary Ellen Mark, among others. In the Foreword to Semetko’s first book entitled Unposed, Elliott Erwitt wrote: “In my book, he is the essential photographer. That is, the one who sees what others could not have seen.”[8]

In 2013, Semetko was paired with his the legendary Erwitt in a “10×10” exhibition that would be unveiled at the 100th anniversary celebration of Leica Photography and grand opening of Leitz Park, the new Leica facilities in Wetzlar, Germany, celebrating 100 years of Leica photography. Semetko elaborated on how this exhibition relates to his work in India for second book, India Unposed, published in 2014, “The decision to shoot black-and-white was made when I was paired with Elliott Erwitt for the 10 x 10 exhibition. The concept was to pair each of the chosen 10 photographers with their respective artistic “fathers.” Leica put Elliott and I together because we both shoot in the street, we are known more or less for the sense of humor in our images, and we both shoot (primarily) in black-and-white. So while I was free to shoot the project wherever and of whatever I wanted, I was asked to keep those three things in mind.”[9]

To describe Semetko as a “street photographer” would be a misnomer. “I don’t really like the term ‘street photography,’ as it’s very limiting. One of my favorite photographs in the India Unposed series is of two young men rowing a boat on the River Ganga. Does that make me a “river photographer?” I think what people mean when they say “street photography”—and I’m not condemning anyone for using the term as I use it myself because it’s the quickest way to generally explain what I do—is a type of photography that is not staged, and captures spontaneous moments of people living their lives, often candidly,” Semetko said.[10]

One of my favorite images by Semetko from his book India Unposed, is that image of two young men rowing a boat in the river Ganga. One man stares fervently into the distance will the younger more innocent looking man behind him stares at the expression on his face. What I love about this black and white photograph is that it draws my attention directly to the emotion on the subject’s face. Commenting on the photographer’s experience in India, Semetko said, “Photographing in India is a photographer’s dream. As a westerner visiting for the first time, my senses were overwhelmed. Everything was new… the sounds, the tastes… and of course the sights. This is wonderful from a photographer’s standpoint. If you’re curious, you see things as a child would – everything is new and fascinating. The challenge I had was how to shoot candidly, as I was easily noticed and constantly approached with requests to be photographed. In the United States, people rarely ask to be photographed; in India, so many people asked to be photographed that I had to change my approach to getting candid photos.” [11]

On his latest trip to India in October 2017, Semetko captured dynamic moments in a wrestling club on the outskirts of Varanasi, India’s holiest city. For this image the use of color is crucial.

Instead of a clash of various colors, the colors bring life to the images. There is so much emotion in the image of the two men wrestling that can be identified through the intense looks on the men’s faces as they struggle. According to Semetko, “Black and white photography is more about form, shadows and human essence. Color tends to be more about color. None of the colors in these images clash. The colors are all from the same palate, so it doesn’t disrupt. The colors in these photos do not distract from the forms, the actions, and the essence of the human activity in the image.”[12]

Every great image has key elements that make it great. Craig Semetko makes it easier to identify these elements, in a video titled “The Photographer’s DIET.”[13]

We learn that DIET is an acronym for four critical elements of a great photograph: Design, Information, Emotion, and Timing. Design consists of the geometric shapes or patterns created between the subjects within the frame. Information is needed to provide the viewers with a “sense of context,” so that they can then “complete the narrative for themselves.” Emotion should be evoked in the viewer. And timing is crucial. “A great photograph can give the impression that it could not have been taken a split second before or after” said Semetko.

Photography freezes a moment in time, a moment of someone’s life. Anything can happen in a second, a blink of an eye. A camera can take a picture, but the photographer is the one who sees the image before it is taken. Today’s smartphones may make it seem easy to take good photographs. But no matter how smart the smartphone, it cannot change the photographer. It is the person behind the camera who has the gift to be able to capture what Cartier-Bresson calls the “decisive moment”.

-

- Spencer, Douglas Arthur. 1973. The Focal Dictionary of Photographic Technologies. Focal Press. p. 454. ISBN 978-0133227192.

- Cartier-Bresson, Henri. India. 1947-1948. Magnum Photos. Punjab, Kurukshetra. Autumn 1947. https://pro.magnumphotos.com/C.aspx?VP3=SearchResult_VPage&STID=2S5RYDI0CKPH

- Burroughs, Augusten. 2016. “William Eggleston, the pioneer of color photography.” The New York Times Style Magazine. Oct. 17. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/17/t-magazine/william-eggleston-photographer-interview-augusten-burroughs.html

- Rowse, Darren. “When you photograph people in black and white, you photograph their souls.” Digital Photography School. https://digital-photography-school.com/discuss-when-you-photograph-people-in-black-and-white-you-photograph-their-souls/

- A brothel hallway at night. http://www.maryellenmark.com/books/titles/falkland_road/300D-001-008_falkrd_520.html

- McFee, Jenny https://jennymcphee.wordpress.com/2012/04/10/the-art-of-voyeurism-in-mumbais-underworld-mary-ellen-mark-sonia-faleiro-and-katherine-boo-my-april-column-at-bookslut/

- Mark, Mary Ellen. 1981. “Afterword” Falkland Road: Prostitutes of Bombay. New York: Knopf. http://www.maryellenmark.com/text/books/falkland_road/text001_falkrd.html#books_falkland_road_afterword

- Semetko, Craig. 2010. Unposed. Kempen, Germany: teNeues.

- The Leica Camera Blog. 2014. Craig Semetko: Inside India Unposed. Aug. 22. http://blog.leica-camera.com/2014/08/22 /craig-semetko-inside-india-unposed/

- Semetko, Craig. 2014. India Unposed. Los Angeles, USA: Street View Press. Interview with author, Oct. 27, 2017.

- Comments to author via email, Oct. 30, 2017.

- Comments to author via email, Oct. 30, 2017.

- Semetko, Craig. The Photographer’s DIET. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qxudPUCN1Uw

© Miriam Isabelle Cherribi