Gastrodiplomacy in Palestine/Israel by Jennifer Shutek

Jennifer Shutek is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Nutrition and Food Studies at New York University, Steinhardt, where she is pursuing research projects on several interwoven topics, including: the social functions of generosity among West Bank Palestinians, the semiotics of agricultural images in Zionist and Palestinian propaganda, the entangled histories of sabich and Arab-Jewish migrations to Palestine/Israel, and gastrodiplomacy in Palestine/Israel and among diasporic Palestinian and Israeli communities in North America. She obtained her BA in Middle Eastern and Islamic History with a minor in English literature at Simon Fraser University and her Master of Philosophy in Modern Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Oxford. Her master’s thesis analyzed narratives of gastronationalism and culinary diplomacy in Palestinian and Israeli cookbooks. She will be returning to Israel in the spring of 2018 as part of NYU’s Provost’s Global Research Initiative program to carry out fieldwork on gastrodiplomacy, food in the arts, and food preparation and consumption during Jewish holidays. Twitter: @quixoticavocado

“You won’t understand Arabs if you don’t understand their food.” A Palestinian-Israeli woman told me this one day as we sat in her living room, the stretching window on the western side of the house overlooking their backyard, containing a gnarled olive tree and a pair of chickens strolling languidly. I spent several days during Ramadan in the summer of 2014 with her, her husband, and four of their seven children in their home in Arraba, an Arab local council in the Lower Galilee region of northern Israel. The family shared their traditions of food preparation and consumption during Ramadan. I visited the family’s bakery, where women sat outdoors stuffing and crimping hundreds of knafeh, half-moon shaped dumplings bursting with cheese or nuts then baked and drenched in syrup; accompanied the children to the sprawling open-air market where they bought a variety of vegetables at their mother’s behest; and shared the iftār, the meal that breaks the day’s fast, as the massive crimson sun slipped below the horizon.

While Arab-Israeli identity is complex and multifaceted, there is truth to her association between identity and food. As noted by Liora Gvion, a scholar who has written extensively on the foodways of Palestinian citizens of Israel, the political identity of Palestinians is often articulated in the relationship between the “discourse of food, the discourse of land and their manifestation in the course of identity creation.” We need only to reflect on our own food-based memories, gustatory markers of holidays and special occasions, or our conceptions of foods that elicit disgust in order to feel on a gut-level the multiple ways in which food shapes our lives and our identities.

I had not thought of this brief conversation in that living room in Arraba for over a year, but was brought back to that moment in which my host so explicitly articulated the ineluctable ties between food and socio-cultural identity – indeed, the necessity of understanding food to understand an entire group of people – while at a panel discussion on the impacts of queer individuals on North American cuisine hosted by New York University’s Fales Library. There, food writer Mayukh Sen related a frequent occurrence: awaking to a barrage of irate e-mails from readers berating him for “making food political.” I was struck by this echo of the discussion in the introduction to M.F.K. Fisher’s The Gastronomical Me, written in 1943, in which she contemplates a question repeatedly posed to her: “why don’t you write about the struggle for power and security, and about love, the way others do?” Why, I wondered, is this accusatory question still directed at those who research and write about food over seven decades later?

As a food scholar, the causal assumption implicit in this claim, that those who attend to the power dynamics and hierarchies built into foodways make food political, bothers me. The notion that scholars and food writers create and then imbue topics of power, gender, and politics into food stems from the assumption that food is frivolous marginalia, a curiosity or light fun. This, in turn, ties to a middle and upper class performativity of wealth through the leisure of cooking, in addition to issues of gender and race implicated in food preparation. Food’s assumed “safe” nature lies in a space of inhering hierarchical gendering of food as female, personal, private, and, most importantly, apolitical. The lifestyle sold around purchasing specialty kitchen appliances or baking to relax oneself because it provides escape is permitted precisely because of the divorce between food preparation and daily unremunerated labour that has historically marked – and still marks – much of food preparation. Individuals who write about the complex interstices in which food operates – related to a whole host of charged issues including land and water access, sovereignty, identity, gendered divisions of labour, migrant labour, and heritage – are not generating these meanings, but rather are lending sensitive ears to the voices of those most involved in acts of food production and preparation.

When I share with others that my scholarly work focuses on foodways in Palestine/Israel, they tend to reply: “how lovely that you’ve managed to find a topic in which you can avoid the politics of the conflict,” reflecting this assumption that food constitutes an apolitical, neutral space. Skepticism about the viability of treating food as something more than Instagram content or an escapist leisure activity increases when I bring up my main area of research: gastrodiplomacy. The concept of gastrodiplomacy rests on the idea that eating together can play a role in mediation of conflict at various levels, from inter-familial strife to diplomatic dinners between heads of state. While this concept may seem facile or whimsical at first blush, an understanding of the importance of food and agriculture within the context of nationalism sheds light on the dynamic potential within food to make important ameliorative contributions in conflict zones.

When seen within the narrative of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, the idea of place-specific food production (that is, agricultural products and dishes that are labelled “Palestinian” or “Israeli”) is not only important for ideological projects of creating and disseminating nationalism, but also assumes a more immediate urgency because it takes place within a context of competing national identities and nation-building projects with a particular power dynamic. Consequently, all issues of cultural identity, legitimacy, authenticity, and tradition are at stake. Any assault represents an attack not only on the identity of a given group, but seems to pose an existential threat to that group’s very survival, because food is taken as an expression of the unique character, culture, and inherited tradition of a nation. In Palestine/Israel, these competing nationalisms vie for exclusive claims on one piece of land, often doing so through appeals to their unique ability to cultivate the soil.

Sam Chapple-Sokol, the leading scholar and practitioner in the contemporary field of culinary diplomacy, has observed that the “power and connection of food and nationalism leads us to consider the potential of using this link as a tool of international relations.” The significance of the connections between food and the reinforcement of a specific nationalist narrative has led some members of civil society within Palestine/Israel to contest and reformulate official narratives and identity politics in the region. Some Palestinians and Israelis are creating points of co-operation by attaching new meanings to food and agriculture, employing the many shared foods and methods of cooking to embark on their own gastrodiplomatic endeavours.

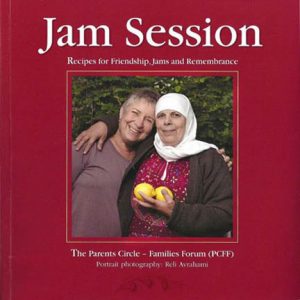

The types of gastrodiplomatic initiatives taking place in Palestine/Israel and among diasporic communities are not official, state-led outreach programs, but instead involve individuals meeting in private, unofficial venues to interact via food. Israeli-Palestinian cooperatives like Sindyanna of Galilee, the educational program Traditional Creativity in the School that brings together Arab and Jewish school children, and jointly authored cookbooks such as the critically acclaimed cookbook Jerusalem: A Cookbook and the community cookbook Jam Session: Recipes for Friendship, Jam and Remembrance contest the dominant historical narrative of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. This is a conflict-reductive narrative that does not allow space for imagining alternative futures because it largely ignores the viability, or even the existence, of past and ongoing peace initiatives. Earlier precedents of food-based collaboration and culinary diplomacy on a grassroots level occurred in Palestine/Israel, too. These include Hawaii Gan, a joint Arab-Jewish restaurant which began operating in the 1940s, and Sea Dolphin, a restaurant jointly owned and run by Arabs and Jews. Another private joint venture relating to food took place in the charged environment of the second intifada, between Israeli celebrity chef and baker Erez Komarovsky, and Palestinian Israeli chef and restaurateur Mahmoud Sfadi, when they “got together as a public statement to cook a meal together.” Today, Majda restaurant provides an unusual model of culinary collaboration. Its owners, a Jewish-Israeli woman and a Muslim-Palestinian man, are not only business partners, but have been a couple for over two decades, demonstrating the possibility of transgressing ethno-national segregation on a commercial and a deeply personal level.

These several examples of initiatives of gastrodiplomacy illustrate the possibilities of using foodways to create dissonance with the standardised narratives of conflict, revenge, violence, and mistrust. The power of foodways to explore identity politics, religion, and ethnicity is significant in Palestine/Israel, where dominant narratives have portrayed a seemingly unbridgeable divide between Palestinians and Israelis, Muslims and Jews. The perseverance of civil-society organisations that promote and facilitate dialogue and coexistence shed light on individuals who are choosing to write about, act upon, and advocate for co-existence, in part by relying on the universal nature of foodways.

In Palestine/Israel, eating together will not provide panacea for debates about one- or two-state solutions, the difficulties and nuances of life for ’48 Palestinians, the myriad social and economic issues faced by Jews of Middle Eastern backgrounds (both historically and contemporarily), or the numerous agricultural guest workers whose illegal presence makes it nearly impossible for them to protest unjust hiring practices and labour conditions. The idea that a Palestinian and an Israeli will share a plate of hummus or share manaqeesh and be transformed into equal partners in pursuit of harmonious existence is, of course, a gross oversimplification, one that I have never heard advocated by practitioners or scholars of gastrodiplomacy.

Sharing food involves engaging in one of the most basic acts of survival in the presence of others, and as a result a host of meanings are involved in communal food preparation and consumption. Take, for instance, the project of creating jointly-authored cookbooks using two examples: Jerusalem: A Cookbook written by Jewish-Israeli Yotam Ottolenghi and Palestinian Sami Tamimi, and the community cookbook Jam Sessions: Recipes for Friendship, Jam and Remembrance compiled by members of the Parents Circle-Families Forum, a joint bereavement group for Palestinians and Israelis. The acts of researching and testing recipes and writing Jerusalem and Jam Session required Palestinians and Israelis to collaboratively engage in the personal, meaningful activity of food preparation. These cookbooks challenge historical narratives of inexorable conflict and, by extension, participate in the creation of models for alternative futures. The imagination of coexistence by interacting with and humanising individuals who have traditionally been seen through the lens of conflict can be a contentious endeavour with larger ramifications because, as noted by history Professor Alon Confino, “empathising with the Other is always political.” The Palestinians and Israelis writing these cookbooks employ the universal cultural artefact of food to problematise the dehumanising portrayals of their Israeli and Palestinian Others, respectively. In doing so, they present deeper challenges to what they see as political and social systems of inequality and oppression in Palestine/Israel.

Although the vast majority of journalistic and scholarly writing focuses on elite male diplomatic and military history and current events in Palestine/Israel (juxtapose, for instance, the amount of virtual ink spilled each time Hamas and Fatah discuss rapprochement with the paucity of articles on organizations like the Parents Circle-Families Forum or Sindyanna of Galilee), few people live their day-to-day lives in spaces of ideology or state-level politics. Instead, our quotidian realities are far more banal, involving micro-interactions, commutes, and mundane decisions about where to shop, what to do with leisure time, and what foods to consume. Within this framework of micro-social spaces, the everyday takes on particular importance, as it is felt, embodied, and repeated on daily, weekly, monthly, and annual cycles which inscribe it into our habitus and experiences of the world.

The topics of resistance and cooperation that challenge conflict-reductive narratives in the charged and heavily mediated context of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict are a sometimes-radical form of subversion that seem to be particularly well suited to and facilitated by the culinary world. The power of food is beautifully articulated by activist and writer Laila el-Haddad, who writes in the introduction to her cookbook The Gaza Kitchen: A Palestinian Culinary Journey: “Nearly everyone in Gaza to whom we explained the project understood it immediately: to talk about food and cooking is to talk about the dignity of daily life, about history and heritage in a place where these very things have often been disparaged or actively erased.”

At the end of the day, issues of a dismissal of food studies often come from a place of assuming that I (and others who consider food as a total social fact) are in some way generating or overemphasizing the significance of food, when the reality could not be farther from the truth. In daily conversations, I have spoken with Palestinian women whose embodied knowledge and roles within their families stem from their preparation and provisioning of meals; I have shared a meal with an Israeli couple who proudly showed me bottles of olive oil pressed from olives grown by the husband’s parents; I was told by an American-Palestinian that she hungrily inhales the aroma of za’atar because it “smells like home”; and I spent a month in the home and kitchen of a Palestinian woman, a leader within her community, who told me that “food is better than prayer.” All of these, and dozens of other similar moments, make it clear that a complex, deep, layered resonance of food exists. It is a reality for the people who share their food, recipes, memories, and political opinions with me, whether they would articulate it using the academic jargon of my discipline or through reminiscences of a childhood or a yearning connection to land. And so, if in my research I chose to ignore the message, repeated over and over again, that food and agriculture figure on political, economic, bio-social, familial, and intimate levels in their senses of self and community, would I not be paying disrespect to these voices and truths? How can I as a food scholar hope to understand others if I do not truly listen to the complex stories that they tell through their foodways?

© Jennifer Shutek