Implementing Psychosocial rehabilitation For War Affected Communities by Dr Daya Somasundaram. BA, MBBS, MD, FRCPsych, FRANZCP, FSLCP, Professor of Psychiatry, University of Jaffna and University Adelaide, Consultant Psychiatrist, Teaching Hospital Jaffna and Tellipalai, STTARS, South Australia.

Co-authored by Mrs. Velintina Sebastiampillaii, Mr. Krishnasamy Iynkaranii, Mr. S.Rathakrishnaniii, Mr.T. Vijayasangariv

(i,ii,iii ONUR MHPSS TOT programme, North, Sri Lanka. iv Shanthiaham)

This is a developed version of the paper presented at the International Conference, “Questions of Memory, Justice and Reconciliation in Societies Post Conflict”,

11- 14 September, 2017, International Centre for Ethnic Studies, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Abstract

The war in Sri Lanka has caused considerable metal health and psychosocial sequelae at the individual, family and community levels. Mixed methods were used to study the effectiveness of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) and rehabilitation using Training of Training approach in northern Sri Lanka. Initial findings are reported that showed resistance at the national, provincial, regional, district and local bureaucratic, administrative and professional levels however there was expression of psychosocial needs from ordinary people and high levels of motivation among the selected trainees. Effective implementation of MHPSS will need to be coupled with adequate awareness creation and advocacy.

Introduction

Individuals, families and communities in Sri Lanka, North, East, so-called border areas as well as rest of Sri Lanka, have undergone twenty five years of war trauma, multiple displacements, injury, detentions, torture, and loss of family, kin, friends, homes, employment and other valued resources (Somasundaram, 2014). There is evidence from several studies of the widespread individual mental health and psychosocial consequences that show high prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Depression, Anxiety, Alcohol and Drug Dependence and Abuse (Husain et al, 2011; Jayasuriya et al, 2016; Fernando & Jayatunge, 2013; Siriwadhana, 2013).

One of the major consequence of the Lankan Civil war has been the internal and external displacement of people. The Tamil Diaspora abroad was estimated to be around one million in 2010, or one quarter of the entire Sri Lankan Tamil population[1] (International Crisis Group, 2010a). A picture of the Internatally Displaced Persons in 2007 (fig. 1), before the massive displacement of over 400, 000 towards the end of the war in 2009 (fig. 2), show the island wide impact. Less has been documented of the psychosocial impact on family dynamics by the displacements; separations; death, disappearance or injury to bread winner, leaving high percentage of female headed households. Whole communities have been uprooted from familiar and traditional ecological contexts such as ways of life, villages, relationships, connectedness, social capital, structures and institutions. These results are termed “collective trauma” which has resulted in tearing of the social fabric, lack of social cohesion, disconnection, mistrust, hopelessness, dependency, lack of motivation, powerlessness and despondency (Somasundaram, 2010). Other adverse post war consequences are shown by social parameters such as increased Suicide and Attempted Suicide rates; Gender Based Violence; Child Abuse; indebtedness; multiple partners and youth antisocial behavior (Somasundaram, 2013). The Consultation Task Force (CTF) report of testimonies from a wide variety of ordinary people brings out the widespread psychosocial consequences (CTF, 2017). Result of ‘town hall’ meetings for the public, focus groups on special subjects, sectorial consultations and individual submission which has a whole section on psychosocial issues (Volume I, section VII part I- pages 359 to 404) and Recommendations which mention need for psychosocial services:

A clear policy on reparations that recognises the right to reparations and a clear set of normative and operational guidelines to give effect to this, should be set out and made public. The right to reparations should be seen as distinct from and in addition to the right to development. The policy should be imaginative and responsive to the various forms of large- scale conflict related and systemic violations that individuals and communities have suffered. It should devise multiple forms of reparations including financial compensation to individuals, families and communities, other material forms of assistance, psychosocial rehabilitation, collective reparations, cultural reparations and symbolic measures.

In a similar context in Latin American country, Peru, recommendations were made for psychosocial rehabilitation and health care as part of the reparation in the conflict affected region:

It is difficult to imagine how the specific needs of massive numbers of victims can be addressed if the ability of the state to comply with its obligations is limited and there is a systemic lack of services for all citizens. A reparations policy on psychosocial support to victims needs to be accompanied by an improvement of the health care system in those areas where it is insufficient. This is one of the main challenges of reparations programming in contexts such as Peru, where guarantees of social and economic rights for citizens lag, making it is even more difficult to provide specialized services to individual victims that are distinctly reparative. (International Centre for Transitional Justice, 2013).

Though there has been massive economic investment and infrastructure development post-war (PTF, 2013) in Sri Lanka, these peace dividends have not reached war affected communities, not aiding their economic or psychosocial recovery (Sarvananthan, 2012). Although nationally Sri Lanka achieved middle income status, there is a widening inequality as conflict affected areas in North and East areas remain below the poverty line (World Bank, 2016). Eight years after the ending of the war, legitimate reparation, community recovery and national reconciliation are yet to take place. Post-war issues causing on-going stress and difficulties for healing and reconciliation are tardy resettlement and return of land; poor regular income, lack of support to return to traditional occupations, few vocational opportunities, continuing militarization, paranoid inter-community relationships, and distrust in state, and non-state institutions and structures (CTF, 2017).

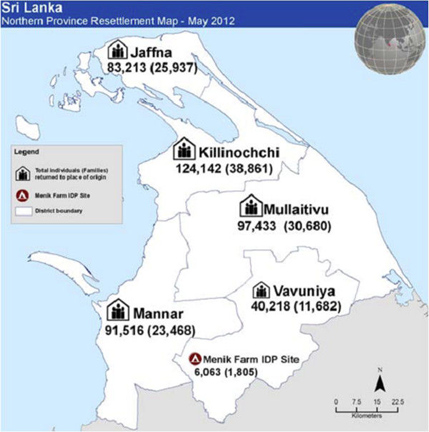

Resettlement process in Sri Lanka in the post war period are yet to be completed. Some resettled areas in Northern Province are shown in the figure 2 below.

War had affected the people at the individual, family, community, society, socio-economic, culture and ecological levels. At the individual level, for example, results from a survey in Jaffna just after the end of the fighting in September of 2009 showed that IDP’s surviving the apocalyptic end of the fighting showed much higher rates of PTSD, Anxiety and Depression compared to people who had not faced the recent ending but had lived through the war and thus still had significant numbers affected (Husain, 2011):

Non-recent IDP’s

– PTSD – 7%

– Anxiety- 32.6%

– Depression- 22.2%

Mental health problems in IDP’s:

– PTSD – 13%

– Anxiety- 49%

– Depression- 42%

IDP’s had significantly higher rates of trauma experience

– 58% experiencing > 10 trauma events &

– 41% with 5-9 events

Due to the war, Muslims who were forcefully expelled from the Northern Province showed Common Mental Disorder (CMD) such as Somatoform disorder -14.0%, Anxiety disorder -1.3%, Major depression- 5.1% ,Other Depressive syndromes -7.3%, PTSD- 2.4% and Total CMD -18.8% (Siriwardhana et al, 2013)

The war in Sri Lanka caused changes at the family level in significant ways. The family is the basic structural unit of the Tamil society. The war has demolished this structure due to deaths (vacuum), separations, disturbances in family dynamics, change in the roles (death of father or mother). These effects must be considered in psycho social rehabilitation for war affected communities.

The effects of the war have been identified in the community level too. Whole communities have been uprooted from familiar and traditional ecological contexts such as ways of life, villages, relationships, connectedness, social capital, structures and institutions which has resulted in tearing of the social fabric, lack of social cohesion, disconnection, mistrust, hopelessness, lack of motivation, powerlessness and despondency (Somasundaram, 2010). This has resulted in widespread poverty, lack of initiative and motive to repair, work or earn, to return to pre-war functioning and income generating efforts. Adverse post-war consequences are shown by social parameters such as increased Suicide and Attempted Suicide rates; Gender Based Violence; Child Abuse; indebtedness; poverty, multiple partners, abysmal educational performances and youth antisocial behavior (Somasundaram, 2013). Socio-economic rehabilitation, development and growth are essential as a part of community recovery.

Unfortunately, the post war, martial style of governance did not permit healing rituals such as mourning for dead, community rebuilding or psychosocial programs (Samarasinghe, 2014). The community and its members need to be able to benefit from the developmental programmes being undertaken. Economic recovery will not be sufficient; people need ‘to reconstruct communities, re-establishing social norms and values’ (Weerackody and Fernando 2011). International law recognizes the Principle of Restitutioadintegrum for the redress of victims of armed conflict to help them reconstitute their destroyed ‘life plan’. This justifies the need for rehabilitation as a form of reparation clarified by the UN ‘Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparations for Victims’ as taking five forms: restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition (UN General Assembly 2005). Rehabilitation should include psychosocial rehabilitation at the individual, family and community levels (Somasundaram 2010; CTF, 2017). In a study (Vijayasangar, 2008) after the Tsunami to find out the reason for failure of livelihood support, out of 160 beneficiaries affected by psychosocial problems, 50% were provided psychosocial intervention and livelihood support, rest of 50% were only provided livelihood support without psychosocial intervention. After nine months, their improvements were evaluated, 60% with the livelihood support and psychosocial interventions showed very good recovery while 28% were successful at an ordinary level. On the other hand, in participants who received livelihood support without psychosocial intervention, less than 42% had recovered. The important lesson was that implementing livelihood support, the psychosocial problems of the beneficiaries must be dealt properly; then only the success rate of livelihood and development support will be useful to the community. Without psychosocial wellbeing and recovery, implementing livelihood support and development will not bring expected better outcomes,

International development efforts elsewhere in post conflict contexts have increasingly adopted holistic approaches that have included psychosocial recovery and rehabilitation through Training Of Trainers (TOT) to widely disseminate basic knowledge and skills to affected populations (de Jong, 2002; Eisenman et al, 2006). In Sri Lanka, the Office of National Unity and Reconciliation (ONUR) has sponsored the first of these efforts. We have embarked on a strategy for post conflict recovery and development based on a public Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) approach. Mixed methods were used to study the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions and rehabilitation. Initial findings from the implementation stage are reported.

Methodology

Literature survey to find best practice for psychosocial recovery and rehabilitation in post war contexts. Qualitative methods including Participant Observation, Key informant interviews of the stakeholders to monitor and reflect; and Participatory Action Research to modify the implementation of psychosocial rehabilitation efforts.

Results

Design

The Government of Sri Lanka established the Office for National Unity and Reconciliation (ONUR) in 2015 to plan and work to achieve national unity and reconciliation. Subsequently, A Task Force on Psycho-social Well-being was set up to address the mental health and psychosocial consequences of the conflict and to develop psychosocial strategies for national reconciliation. A major proposal put forward by the Task Force was to implement a Training of Trainers in Psychosocial work. For this purpose, the protocol developed by Joop de Jong of the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization, a WHO collaborating centre, working around the world to relieve the psychosocial problems of people affected by internal conflict and war (de Jong, 2002, De Jong, 2011) that one of the authors had the opportunity to implement in Cambodia (Van de Put et al., 1997) and Jaffna (Somasundaram and Jamunanantha, 2002), in which one of the authors was a trainee, was adapted. Government, Non-Governmental workers were to be trained to train government, Non-government and village resources (Core Group volunteers) to address the MHPSS needs of people using individual, family and community level interventions. The training uses evidence based best practice including psychological first aid, psychoeducation, counselling, family and women empowerment group work, child and youth support and activities; testimonial and narrative methods, ventilation through creative arts and drama; Problem Management +, Psychosocial support for Transitional Justice and reconciliation processes. It also includes traditional methods such as calming techniques, memorialization and healing rituals as well as promoting inherent strengths and resilience factors to rebuild communities through intersectoral collaborations and networking for education, nutrition, livelihoods, income generation, vocational training, legal aid, housing and other facilities.

For long term sustainability and effectiveness, it was felt that the capacity for psychosocial work had to be developed within the state structures and institutions functioning at the ground level, particularly in the war affected areas. In view of the widespread traumatisation and consequences of the war, affecting large number of the population, the Task Force identified state officers working at the Divisional level[2] as those dealing directly with the public and thus most suitable to target for the psychosocial training. Each divisional level has over 35 categories where graduates are appointed to carry out various grass root services. The Task Force felt many of these officers could effectively carry out psychosocial support while attending to their regular work (see Table 1)

Table 1 List of Officer related to Mental Health & Psychosocial Support at the Field Level

| Working within DS[3] office | Working Outside of DS Office |

| Women’s Affairs | Education |

| Women Development Officers | Guidance and Counselling Teachers |

| Relief Sisters | Guidance and Counselling In-Service Advisors |

| Development Officers-Counseling Assistants | Health |

| Child Development | Medical Officers Mental Health (MOMH /MO Psychiatry) |

| Probation Officers | Community Support Officers / Psychiatric Social Assistants (Some districts only) |

| Child Right Promotion Assistants | Psychiatric Social Workers |

| Child Rights Promotion Officers | Health Education Officers |

| District Psychosocial Officer / Coordinator (NCPA[4]) | Medical Officers Maternal and Child Health (MOMCH) |

| District Child Protection Officer (NCPA) | Mithuru Piyasa / GBV Desk Personnel (usually Nursing Officers) |

| Child Protection Officer | |

| Early Childhood Development Officers/Assistants | |

| Social Services | |

| Social Service Officers | |

| Development Officers (Social Service) | |

| Development Officers (Counselling) Counselling Assistants (MoSS). |

The Task Force decided to implement the TOT, first as a pilot project in the north Sri Lanka and subsequently, if effective, in the East and other provinces. The ONUR had a policy of working through the government machinery nationally and locally, which meant the various ministries, district secretariats and provincial government. In view of the expected logistical and financial bureaucratic difficulties and delays in working through government machinery; a long-time, local NGO functioning in counselling and psychosocial fields the north, Shanthiaham, was co-opted to smoothen the implementation.

It was initially decided to recruit 30 Government officers (six per district) and 10 non-state candidates (two per district) for this project. Later, when there were long delays in the release of selected state officials, ONUR agreed to the recruitment of 10 additional unemployed graduates, most of whom had been staging continuing protests to be employed by the state.

The following activities were implemented to conduct this training programme: Advocacy programme were conducted to District Secretaries (Government Agents- GA) of five districts in Northern Province. Each GA was asked to nominate 10 suitable candidates using the following criteria:

- Is prepared to reside and work in the district for at least 2 years after the training period

- Preferably has had training and experience in counseling/psychosocial work / social mobilization/GBV/child protection: i.e. Counselling officers/assistants, PO/CRPO, MOMH, WDO[5], PSW? Departments such as Health, DPCC, DS, Youth Services Officer may nominate a participant.

- Has demonstrated commitment to work within the community, and is highly motivated.

- Indicate willingness to learn and train others

- Has previous teaching experience

- Preference should be given to female trainees if the criteria above have been satisfied.

Unfortunately, the circular to GA’s had a subject line saying Psychosocial counselling programme and the District Secretariat mechanism proceeded to nominate only those directly involved in Counselling such as the Counselling assistants. To elicit applications fulfilling above criteria and with motivation to train others in psychosocial work, applications were solicited through regional networks and advertisement in local and national media. A similar process was followed for seeking applicants from the non-state sector and for two Research Assistants (RA’s).

TOT selection

All applicant’s background was checked through the MOMH, local government officers and other community leaders for work performance, commitment and attitude. Then an evaluation exam was conducted to these applicants where IQ, motivation, aptitude, attitude, and social knowledge were assessed. Higher scoring applicants and those found suitable through the background check were interviewed, again mainly looking for above criteria; representation from district, gender, socioeconomic background, caste, ethnicity, physical handicap, origin from Hill Country, and mainly motivation and commitment. 30 government staffs (all graduates), 20 non-state and 2 RA candidates were recruited through interview, selection process was finalized with consent of MOMH and Government higher officials.

Releasing Government staffs

After selection, obtaining the release of the state officers proved difficult. Details of selected Government officers was sent to the head office of ONUR to secure their release from respective Ministries in the capital, Colombo. Even after 6 months this process, which included high level negotiations with authority and more local negotiations, was not complete but the officers coming under the Provincial Ministries were released after some local negotiations. .

Participatory Observation and Key Informant interviews of involved authorities revealed poor understanding about psychosocial issues, causative factors and effective implementation strategies. There was a general denial and an attitude among the administrative and professional structures, at the national, provincial, regional, district and local levels that psychosocial issues were not a priority. The urgent need was felt to be livelihood and income. Psychosocial was considered a ‘soft’ program, while economic aid and vocational support were termed ‘hard’ projects that needed urgent attention and implementation. Psychosocial support was commonly (mis)perceived as ‘counselling’, merely one to one advice, a conception that resisted explanations and discussion. Understanding of such psychological phenomena as motivation, participation and effects of past trauma in these rehabilitation and developments programs were minimal. However, a district Director of Planning expressed her concern that ‘all the livelihood projects that had been implemented so far had been ineffective and psychosocial issues had to be addressed’. Yet, a local psychiatrist said that ‘people will recover by themselves, they do not need any psychosocial interventions’.

Resistance to release of Government officers were found to be due to various reasons and factors. In contrast, all the non-state candidates joined the PS TOT without any difficulty, mainly it was said due to the employment opportunity with regular salary, particularly in a quasi-state structure, but many showed high motivation and commitment that had also been a key selection criterion. As far as the state sector, ministries were reluctant to release the selected candidates full time, as they felt they had other important responsibilities. After several negotiatory meetings and long delays (beyond the initial training period), most ministries agreed to release their officers part time. At the district and divisional levels, it turned out the selected candidates were high functioning, responsible officers on whom the government machinery was dependent (not surprising at all given the assessment and selection procedure). In one case, the administrator declared the whole district office would stop functioning without that person! Administrators also warned the candidates of risks to their regular salary payments, pension, seniority and future in the government if they went to this ONUR or sometimes seen as a Shanthiaham (a non-state body) program, which was portrayed as non-secure. Due to the long delay, some candidates had been transferred to other position, sometimes out of the district, or been offered other attractive possibilities such as post graduate study (one candidate managed to finish a post graduate diploma during the long delay between initiation and start and then join the first training session), scholarship abroad and promotions to higher positions. Some candidates suggested by ministries[6] had found their positions comfortable and convenient, giving them opportunity to be close to home and attend to other responsibilities, or draw high allowances and benefits which they would lose by joining the TOT for one year. Some of the GA’s agreed to release some of the selected officers part time, pending the official release from their respective ministries. Key informant interviews with relevant government authorities at the district level revealed apprehensions concerning psychosocial programmes. Psychosocial work had been banned during the previous martial governance and many of the local authorities appeared to have internalized the strict controls, so that even after changes in the regime, they continued to be uneasy about psychosocial programmes, felt something was inherently wrong with them. Some expressed fears about the return of the previous regime which would then put them in danger for allowing the functioning of psychosocial programmes. There was also a general fear about possible audits, as was happening often under the present regime, and wanted to follow strict procedures, not willing to take risks, particularly in relation to matters with financial implications. Many wanted any decision made from Colombo or higher up in the hierarchical authoritarian system, leaving them blameless as following orders.

Curriculum

The curriculum for this training was based on the 3rd edition of the manual, “Mental Health in the Tamil Community”, originally adapted from the WHO/UNHCR (1996) booklet, “Mental Health of Refugees”, The duration of this training was two months, divided into three phases with the first two weeks devoted to theoretical teaching with practical role plays and discussion.. Experienced resources persons who had previously worked during the man-made and natural disasters from Northern Province, particularly psychiatrists, counsellors, psychosocial trainers and overseas experts conducted the training.

A pre-test was conducted on the first day and the training programme modified according to the daily evaluations given by the participants. For example, trainees reported lecturers were often using English terminology which they did not understand nor were their explanations given. Accordingly, lecturers were requested to minimize English usage, or at least, give explanations for the English terminology. It would found that the trainees became more familiar with the more common English terminology and started using them appropriately themselves. Later, it was found helpful in their communicating with their field supervisors and co-workers.

After the two weeks they were sent to their own districts for field experience under close supervision. The purpose of this training was applying theories which were taught in the classroom to gain experiences and understand the practical implications. Once a week TOT were trained in the mental health units in their own districts through Medical Officers of Mental Health (MOMH). Every week, counselling and psychosocial supervision were provided for clients they were seeing.

This field experience training programme was structured with the following steps:

- Village assessment

Information, mainly demographic and other vital statistics including incidents of mental health issues, were gathered from the district, consecutive administrative heads, Government Agent (GA), Divisional Secretary (DS), Gramma Sevaka (GS)- the earlier village headman, psychiatrist, MOMH, counsellors, psychiatric social workers, health workers, psychosocial workers, representatives of the Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO’s), Community Based Organization’s (CBO’s) and village resources from that region. At the same time, the opportunity was used to build up a working relationship and network with these officers.

- Selection of the village

Selection of the villages for psychosocial interventions, initially two per district, were done after discussing with the above mentioned resource persons based on the following indicators: Poverty, indebtedness, affected due to severe war (death, injured, missing), Displacement, Resettlement, Socioeconomic problems, malnutrition, Domestic violence, Alcohol and drug abuse, previous Natural Disasters (e.g. Tsunami), Child abuse, rates of suicides and attempted suicide, prevalence of minor and major mental health disorders.

- Obtaining permission

Permission had been obtained from the government authorities to work in the selected villages. E.g GA, Divisional Secretariat, Grama Sevaka Officers.

- Integration with people

Integration with people was carried out through introduction of the following in the selected Villages; About the worker, About the organisation, About the intention of the activities.

- Meeting with small groups

To do the initial works, we discussed with the most important resources from the village and got their whole support and permission.

- Cross walk

Looking around all the nook and corners of the village.

- Learning the society

Getting to know the language, culture, traditions, rituals, habits, way of life and occupations with the help of the important resources who were living in that area.

- Data collection and documentation

Data collection and documentation needed for our work (e.g. How many people died, separated, missed, widowed and drop out children from school, various psychosocial indicators).

- Social Mapping of the community

Social mapping of the community via making the peoples to draw with our facilitation. In this the infrastructure, the environment of society, situation of important structures, institutes, settlements, pockets of high physical, psychological and social problems would be reflected. Further, the place in which the collective trauma occurred (e.g. specific area which lots of people died because of bombing), the house of the community leader, temples, CBOs, Traditional leaders also would be mentioned.

- Identifying and analysing the problems

Identifying and analysing the problems with the help of core resources:

(a) Key informant interviews (talking individually with the people with experience in the society e.g. community leaders, leaders of the women development centre, religious leaders, teachers, elders).

(b) Focus group interviews (based on male and female group work, discussions and presentations, to tackle the problems gathered from above mentioned key resources, school students, university students.

- Planning

Planning were based on the above mentioned identified problems and their priorities, e.g. children who are affected due to war, alcohol problems, domestic violence, attempted suicide, indebtedness, poverty .

- Finding a satellite point for the psychosocial workers

This place was needed for the following purposes: to fulfil the day to day functions, store documents, when the social workers have to stay in that village, to do counselling or relaxation for some of the identified cases, to welcome the needy peoples and provide support for them. Generally, this satellite point is a common building or a pre – school building or private house.

- Community meeting and awareness

At first, planning was done with the key resources, then meetings with the whole community, explaining about the plans and the possible benefits to the society, advocacy and awareness about psychosocial wellbeing. Alternatively, these types of community awareness was done based on the prioritised problems of the community, e.g. Alcohol awareness, awareness of child abuse, domestic violence, indebtedness.

- Selection of the core group

Selection of core groups to identify the present and future problems in their own community and deal with them, to refer and network. Hence, they were selected from pro-social, active, accepted volunteers from the community. The core groups were made up with retired teachers, university students, farmers, youths, respected villagers, religious leaders and traditional healers containing 15 – 20 people with gender balance also.

- Core group training

At the beginning this training programme is for 70 hrs. There will be two sessions per week. Each session runs for 2 hrs. Mainly the training is focussed on psychosocial well-being and psychosocial problems in the village level, basic psychosocial assessments, interventions, support, rehabilitation and follow up, referral and networking.

- Working with the Core Group

The Core Group joins together with the TOT or already trained psychosocial workers (PSW), helping and supporting, but also learning at the same time e.g. Social mobilization for community awareness, involving with the psychosocial worker in the children group activities, helping to identify the psychosocial problems in the community, carrying out psychosocial interventions, referrals, follow-up, rehabilitation till they have mastered the skills and will be able to work independently with follow up support. Then the psychosocial workers will hand over the psychosocial works of that village to the trained core group members.

- Core Group follow up

After the PSW’s hand over the village to the Core Group, the Core Group members from the particular village will continue to function. The technical supervision and up to date training in various relevant subject would be provided to them. This will be conducted every fortnight.

- Essential Psychosocial interventions.

| Individual | Family | Social |

| Case identification | Psychoeducation | Awareness – Psychoeducation |

| Psychoeducation | Family counselling | Discussion and Training |

| Counselling | Strengthening the family dynamics, e.g. Talking and eating together | Intervention for special groups (children, widows, widower, youths etc.) |

| Other Psychotherapy, including elements from Interpersonal, CBT, CEAT | Family Reunification & Unity | Encourage to do religious rituals and traditional healing |

| Problem Management + | Problem Management + | Problem Management + Group |

| Traditional Relaxation methods | Traditional Relaxation methods | Traditional Relaxation methods |

| Expressive methods like art and music | Social support | Encourage to do cultural activities, ceremonies, memorialization’s |

| Family & social support | Income generation | Forming and reactivating the CBOs which are not in function. |

| Referral and net work | Follow up | Creating interpersonal relationships, trust and mutual obligations with each other. |

| Income generation | Network with other NGOs | |

| Rehabilitation | Promoting a good network and reconciliation with other communities. | |

| Follow up | Transitional Justice |

- Referral

The problems, particularly major mental health disorders or socioeconomic and legal issues, which the psychosocial worker is unable to handle or there is no progress after interventions, were referred to counsellor or the nearest psychiatric unit.

- Network

Often affected person needed some material support such as income generation. So, referrals are done to the appropriate organisations.

- Follow up

(a) Individual and family follow up: Monitoring how they take the drugs, follow the advocacies, livelihoods, wellbeing and giving some further essential support to them.

(b) Social group follow up: e.g. Children, women, elder’s groups.

- Supervision for the psychosocial workers

This supervision is for a day in the week. This is a technical supervision for the worker in the field. Especially supervising their activities and counselling.

- Monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring and evaluating the works in the field was ongoing. There were two RA’s continuously documenting the implementing process gathering data, using quantitative and qualitative methods, including Participatory Action Research to use feedback to modify the programme.

Case Studies

Following initial case studies are from the field experience of the TOT’s:

Case study 1

A 41 years old married lady from Puthukudigiruppu Mulliththivu, was facing domestic violence due to her husband abusing alcohol. She has 3 daughters and a son who had got married at age 17. Her seven years old daughter does not have interest to go to school, eight years old daughter has fear to wear dress and sixteen year age of daughter is a mentally retarded. The lady has scars and wounds in her body from the violence. She has psychological symptoms such as sadness, crying, hopelessness, lack of interest in day to day activities, concentration difficulties and avoidance. She was trained to do breathing exercise, other relaxation techniques and offered be-friending, further her sixteen years old daughter was referred to a psychiatrist in Mullaiththivu. Her daughter who fears to wear dress is receiving treatment through Art therapy.

Case study 2

A 43 years old woman from Mannar is working as a teacher. She had lost her husband in the last battle. She was born as Hindu but converted to Christianity now. She has four children, she is living with her elderly mother. Her brother who was wounded in the war died two years ago. Her father died one year ago. She is suffering from grief reaction. The Principal of her school labels her as “affected teacher”. The Christian priest blames her that she is not fully following Christianity, because she was born as Hindu. She was offered grief counselling. She has started telling her own story without crying and writing her story now. She has love and affection for her children. Continuous psychosocial support is provided by the TOT to her.

Update

Following almost two months field experience, the TOT’s were given further training in Problem Management+, including the Group format, training methodology and Transitional Justice issues such as general introduction to the four mechanisms and psychosocial chapter by CTF members and international experiences from an expert from abroad. Further updates are to be in Psychosocial First Aid (PFA), family and group therapy and Child Well-being management.

Limitations to Implementation of psychosocial program

- Difficulties in working with government machinery and bureaucracy.

- Lack of understanding and support from administrative structures to implement psychosocial program.

- Financial restrictions and tight budget.

- Concern for rigid procedures and rules, lack of flexibility and innovations to meet needs.

- Reluctance to assume responsibility or initiate independent action.

- Restrictions and difficulties in travel to cover remote locations and villages.

Conclusions

Effective implementation of MHPSS will need to be coupled with adequate awareness creation and advocacy at policy, administrative, political, authority and professional levels. Negative attitudes could hamper recovery and rehabilitation programmes.

[1] Tamil Nadu (200,000); Canada (300,000); Great Britain (180,000); Germany (60,000); Australia (40,000); Switzerland (47,000); France (50,000); Netherlands (20,000); U.S. (25,000); Italy (15,000); Malaysia (20,000); Norway (10,000); Denmark (7,000); New Zealand (3,000); Sweden (2,000); South Africa; Gulf States, Thailand, Cambodia, Singapore. The largest Sri Lankan Tamil city in the world is Toronto (approximately 250,000), outnumbering Colombo and Jaffna (about 200,000 each).

[2] Sri Lanka is administratively divided into 9 provinces which have 25 districts, further divided into sub-units known as divisional secretariats.

[3] District Secretariat

[4] NCPA-National Child Protection Agency; MoSS- Ministry of Social Services; MO- Medical Officer

[5] PO- Probations Officer; CRPO- Child Rights Protection Officer; WDO- Women Development Officer; DPCC- Department of Probation and Child Care; GBV- Gender Based Violence

[6] For example, the Ministry of Social Empowerment offered to release any of their counselling officers working in the north when the ONUR ran into difficulties recruiting candidates. But all the officers contacted refused due to above mentioned reasons. It was generally found that most state officers, all recent graduates, developed attitudinal and self-interest changes once appointed to government services, though there were notable exceptions which the TOT selection process tried to pick up. One main aim of the TOT program was an attitudinal change.

References

Consultative Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms (2017) Report. SCRM: Colombo. http://www.scrm.gov.lk/documents-reports

De Jong, J. (2002). Public Mental Health, Traumatic stress and Human Rights Violations in Low-income Countries: A Culturally Appropriate Model in Times of Conflict, Disaster and Peace. In J. De Jong (Ed.), Trauma, War and violence: Public mental health in sociocultural context (pp. 1-91). New York: Plenum-Kluwer.

Dinuk Jayasuriya, Rohan Jayasuriya, Alvin Kuowei Tay, Derrick Silove (2016) Associations of mental distress with residency in conflict zones, ethnic minority status, and potentially modifiable social factors following conflict in Sri Lanka: a nationwide cross-sectional study, Lancet Psychiatry. www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Published online January 12, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00437-X

Eisenman, D., Weine, S., Green, B., de Jong, J., Rayburn, N., Ventevogel, P., Keller, A. and Agani, F. (2006) The ISTSS/Rand Guidelines on Mental Healtha Training of Primary Healthcare Providers for Trauma-Exposed populations in Conflict-Affected Countries. Journal of Traumatic Stress, Vol. 19:1, pp. 5-17.

Farah Husain, Mark Anderson, Barbara Lopes Cardozo, Kristin Becknell, Curtis Blanton, Diane Araki, Eeshara Vithana (2011) Prevalence of War-Related Mental Health Conditions and Association With Displacement Status in Postwar Jaffna District, Sri Lanka. JAMA,306: 5, 522-531

Fernando, N. and R. Jayatunge (2017). Combat Related PTSD among Sri Lankan Army Servicemen. In Jayatunge, R. Essays in Psychology. Colombo: Godage publishers

International Centre for Transitional Justice Report (2013). https://www.ictj.org/sites/default/files/ ICTJ_Report_Peru_Reparations_2013.pdf

Presidential Task Force for Resettlement Development and Security –Northern Province (PTF) (2013). From Conflict to Stability –Northern Province, Sri Lanka. Colombo, Presidential Task Force (PTF), from http://www.defence.lk/news/pdf/From_Conflict_to_Stability_20130128_04.pdf

Somasundaram, D. (2013) Psychosocial Rehabilitation in a post – war context- Northern Sri Lanka in 2013 and beyond. Prof. Sivagnanasundram Oration 2013, Jaffna Medical Association Annual Sessions, Jaffna.http://issuu.com/jaffnamedicalassociation/docs/oration-psychosocial_rehabilitation

Samarasinghe, G. (2013). Psychosocial Interventions in Sri Lanka – Challenges in a Post-War Environment. In D. Somasundaram, Scarred Communities- Psychosocial Impact of Manmade and Natural disasters in Sri Lankan Society. New Delhi, Sage.

Sarvananthan, M. (2012). Political spin of the economic growth in the North. Colombo, Sunday Times, from http://www.sundaytimes.lk/120527/BusinessTimes/bt09.html

Siriwardhana, C., A. Adikari, G. Pannala, S. Siribaddana, M. Abas, A. Sumathipala and R. Stewart (2013). “Prolonged Internal Displacement and Common Mental Disorders in Sri Lanka: The COMRAID Study.” PLoS ONE 8(5): e64742

Somasundaram (2014) Scarred Communities- Collective trauma, Psychosocial Impact of Disasters on Sri Lankan Communities. SAGE Publications, New Delhi.

Somasundaram, D. (2010) Collective trauma in the Vanni- a qualitative inquiry into the mental health of the internally displaced due to the civil war in Sri Lanka, International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 4:22, http://www.ijmhs.com/content/4/1/22

Somasundaram, D. (2010). Preliminary Thoughts on Psychosocial Rehabilitation after Mass Atrocities. Rehabilitation as a Form of Reparation Opportunities and Challenges. Essex University, UK, REDRESS & Transitional Justice Network.

Vijayasangar, T. (2008) Psychosocial support in recovery programs, Shanthiaham, Jaffna, In Press

Weerackody, C. and S. Fernando, Eds. (2011). Reflections on Mental Health and Wellbeing. Learning from communities affected by conflict, dislocation and natural disaster in Sri Lanka. Colombo, People’s Rural Development Association.

World Bank. 2016. Sri Lanka – Ending poverty and promoting shared prosperity: a systematic country diagnostic. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/363391467995349383/Sri-Lanka-Ending-poverty-and-promoting-shared-prosperity-a-systematic-country-diagnostic

Abbreviations

CBO: Community Based Organization

CBT: Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

CEAT: Creative and Expressive Arts Therapy

CG: Core Group

CMD: Common Mental Disorder

CPO: Child Protection Officer

CRPA: Child Right Promotion Assistant

CRPO: Child Rights Protection Officer

CSO: Community Support Officers

CTF: Consultation Task Force

DCPO/NCPA: District Child Protection Officer (NCPA)

DO/C: Development Officers (Counselling) Counselling Assistants (MoSS)

DO/SS: Development Officers (Social Service)

DO: Development Officer

DPCC: Department of Probation and Child Care

DPO/NCPA: District Psychosocial Officer / Coordinator (NCPA)

DS Office: Divisional Secretariat Office

DS: Divisional Secretary

ECDO: Early Childhood Development Officers/Assistants

GA: Government Agents

GBV: Gender Based Violence

GBV: Gender Based Violence

GCT: Guidance and Counselling Teachers

GS: Gramma Sevaka

HEO: Health Education Officers

ICES: International Centre for Ethnic Studies

IDP: Internally Displaced Person

ISA/GC: Guidance and Counselling In-Service Advisors

MH: Mental Health

MHPSS: Mental Health and Psychosocial Support

Mithuru Piyasa: GBV Desk Personnel (usually Nursing Officers)

MO: Medical Officer

MOMCH: Medical Officers Maternal and Child Health

MOMH: Medical Officer Mental Health

MoSS: Ministry of Social Services

NCPA: National Child Protection Authority

NGO: Non-Governmental Organisations

NGO: Non-Governmental Organization

ONUR: Office of National Unity and Reconciliation

PO: Probations Officer

PS: Psychosocial

PFA: Psychosocial First Aid

PSA: Psychiatric Social Assistants

PSW: Psychiatric Social Worker or Psychosocial Worker

PTF: Presidential Task Force

PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

RA: Research Assistants

SCRM: Secretariat for Coordinating Reconciliation Mechanisms

SSO: Social Service Officers

TOT: Training Of Trainers

TPO: Transcultural Psychosocial Organization

UN: United Nations

WDO: Women Development Officer

WHO: World Health Organization

YSO: Youth Services Officer

© Dr Daya Somasundaram