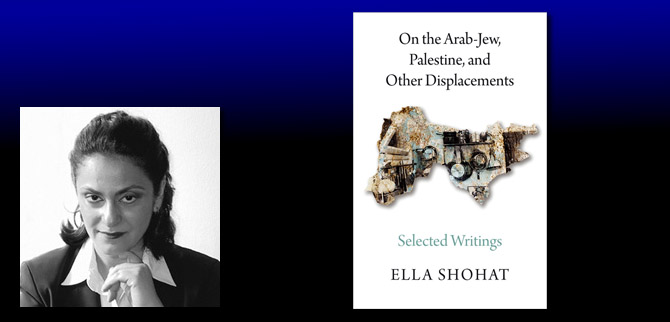

Bodies and Borders – Professor Ella Habiba Shohat

Spanning several decades, Shohat’s work has introduced conceptual frameworks that have fundamentally challenged the conventional understandings of Arabs and Jews, Palestine, Zionism, and the Middle East. Collected now in a single volume, this book gathers together some of her most influential political essays, interviews, speeches, testimonies, and memoirs for the first time – On the Arab-Jew, Palestine, and Other Displacements LINK

An Interview Conducted by Manuela Boatcă and Sérgio Costa.*

Preface by Manuela Boatcă and Sérgio Costa: Scholar Ella Habiba Shohat has long dealt with the real and imaginary boundary lines that inform some of the most insidious conflicts of our times. She defines herself as an “Arab-Jew” of Jewish-Baghdadi background, who has made the U.S. her adopted home, where she is Professor of Cultural Studies at New York University […] Her work unsettles and reinterprets the boundaries between “the West and the Rest,” as well as between the global South and global North. We spoke with Ella Shohat in a Berlin restaurant about the politicization of culture and the culturalization of politics. Here she tackles such varied subjects as the intimate connections between Jewish and Muslim histories and culture and the debates over circumcision, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism, always in a sensitive and empathetic manner, while still retaining analytical distance and a sharp theoretical vision.

Sérgio Costa: As you know, politics in the post-war world was dominated by the presence of nation-states, and intellectual debates were very much shaped by a feeling of national belonging. Intellectuals were, in a certain way, pressured to declare their loyalty to a single national state. Your biography and your oeuvre are very much in-between—between national belongings, between ethnic belongings, and without a fixed national position. Could you please tell us about your trajectory and how this in-between positionality has influenced your work?

Ella Shohat: After World War II, with decolonization and partitions, life shifted for many communities. There were transfers of populations, wherein one identity was transformed into another identity. A Muslim Indian became a Pakistani. In our case, Arab Jews became Israelis. All of this happened virtually overnight. These new official identities did not reflect the feelings of the displaced people, and could not translate the contradictions on the ground. This new situation did not necessarily reflect those communities’ sense of belonging. Hence, a crucial tension was generated between one’s official documentation and one’s emotional map of identity and sense of home and belonging. I have tried to explain this historical context in order to make sense out of our brutal rupture in the wake of partition. I grew up in Israel as a Jew, in a country that defines itself as a state for the Jews and as a Jewish state, which was presumably a solution for “the Jewish problem.” But for which Jews, and a solution for what? Being schooled in Hebrew in a Jewish state required that I completely reject everything associated with my home: namely, the Arabic that we spoke at home; my Iraqi parents; my Iraqi grandparents who didn’t speak a word of Hebrew. The fact is that many people in my community missed Baghdad. But in this context, Iraq and the Iraqis were the enemy of the state to which we now officially belonged. I often describe my experience as a child as one of virtual schizophrenia, where I had to simultaneously live two identities, one outside of the home and another inside the home.

In 1948, after the partition of Palestine, a huge number of Palestinians were dispossessed and became refugees. Many ended up in neighboring countries, in Syria, in Iraq, in Lebanon, in Egypt (not to mention other parts of the world). What was the impact of Palestinian dislocation on Arab Jews? The Arab Jews never suffered a holocaust in the Arab world, but the emergence of Zionism and the situation with Palestinians created intense anxiety. It was no longer possible to simply be a Jew cohabiting with Arab Christians and Arab Muslims. But while Arab Christians and Arab Muslims could maintain their identity, Arab Jews could not. Suddenly, we had to choose between a Jewishness that was equated with Israel, seen as virtually coterminous with the West and with Europeanness, versus an Arabness that was now equated with Islam and the East, and for the first time, an East without Jewishness. The conflict between Israeli Zionism and Arab nationalism generated a situation where we had no place.

SC: What role did religious practices play in relation to these identity constructions?

ES: It is often forgotten that there have always been tensions—including in Europe and the Americas—between Zionist Jews and those religious Jews who from the very beginning thought Zionism was an aberration because it was secular. They believed that the only acceptable moment to return en masse to the Holy Land would be with the coming of the Messiah. (Many secular Jews were also skeptical.) But, after the Holocaust, the Zionist perspective gained momentum and came to be seen as more legitimate among Jews, slowly becoming a kind of normative discourse.

It is also problematic when the history of Jews in Arab countries and in Islamic spaces is viewed as being identical to the history of Jews under Christianity—that is, as a history of relentless persecution. Today, this narrative has unfortunately become a dominant—and, I would argue, Eurocentric—mode of representing Jewish histories.

Even Orientalists such as Bernard Lewis, despite the problems with many of his formulations, did recognize the existence of a “Judeo-Islamic symbiosis.” The Judeo– Muslim dialogue was both cultural and theological. So, although there were certain moments in the history of Jews within Islam where discrimination, and sometimes even persecution, took place, there was also a pattern of strong cultural affinities and relatively peaceful co-habitation. In any case, Jews were not the only minority in a Middle East replete with ethnic and religious minorities; thus, our history cannot be discussed only in relation to Jews within Christian Europe, but must be discussed also in relation to the diverse minorities in the Middle East.

Manuela Boatcă: There seems to be little awareness of the location of Jews within a global perspective. In Europe and the U.S., and perhaps in other parts of the world as well, many people see Jews as always and everywhere European, a view that excludes not only Arab Jews but also Latino Jews and African Jews. Would you say that this is part of the construction of Jewishness as Whiteness? Do you think that this has something to do with the way that the Jewish Diaspora is constructed in terms of European history to the exclusion of other parts of Jewishness across the world?

ES: Yes. Because of a certain Eurocentric discourse, it has been difficult to articulate a Judaism embedded in Arab culture. With colonial domination in the Middle East and North Africa, certain institutions gained power, including Euro-Jewish institutions that were connected to colonial power, which were instrumental in our Westernization even before the arrival to Israel. For example, the Alliance Française Israelite, or the Jewish French schooling system, was established in North Africa, Lebanon, Iraq, and Turkey. As part of French enlightenment, the Alliance combined a French education with a kind of secular Jewish education, all in the French language. But this Western influence existed even before French colonial rule or outside its colonized territories, in places that were still under the Ottoman Empire before World War I. In Baghdad, the Alliance Française-Israelite continued after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, when Iraq came under British influence. French Jews saw themselves as instruments of reason and civilization and extended this view even to their co-religionists within the Islamic/Arab world. It was not only the French state that promoted this “civilizing mission;” the French Jews believed in it as well and spread it to non-Western spaces.

MB: This hegemony of the White European Jew seems to be a quite recent moment, yet the whitened European Jew is also a moment in the history of Jewishness. What do you think of that schism?

ES: I think it is fascinating because the whitening of the Jew takes place on several levels. If we go back to Iberia, with the Inquisition and the limpieza de sangre (the purity of blood), we see that the diabolization operated against the Jew and the Muslim together. And racist discourse, especially as it culminated in 19th-century scientific racism, categorized Jews along with Asians and Africans, for example, as inferior. Hegel’s “idealist” approach in The Philosophy of History sees diverse peoples, especially Africans and Jews, as living “outside of History”—a highly problematic concept: how can any community be regarded as living outside of history, outside of time and place?

Zionism can thus be seen as the response, at the discursive and theoretical level, to these prejudicial discourses, an attempt to place the Jew inside of history. Theodor Herzl’s visionary utopia Altneuland has the “New Jew” transforming Palestine, imagined as a backwater, into a modern, civilized space. In a way, Herzl was responding to anti-Semitic discourses about the Jew. Zionism, to my mind, can be described as an effort to whiten the Jew philosophically and even literally. The ideal of the New Jew was posited in contrast to the anti-Semitic stereotype of the Ostjuden: a kind of feminized, weak, wandering Jew, a luft-mensch pondering texts. The New Jew was to be masculine and a worker of the land, grounded in nature, no longer the cosmopolitan exiled diasporic but a Jew who has returned to his homeland. The notion of the New Jew was influenced by the Jugendkultur, or youth movement in German, and appeared in Hebrew novels and Zionist and (later) Israeli cinema; the hero would often be blond, blue-eyed, or at least light skinned, and of course never graced with the stereotypical hooked nose. This de-Semitization took place within the logic of Western hegemony, somewhat like the case of the Aryanization of Christ in European painting. And therefore one can argue that there has been a kind of Aryanization and whitening of the Jew as a result of the experience of anti-Semitism. Moreover, Israel was created with the idea that it would be a Western outpost—a Switzerland of the Middle East, as the phrase went—even though located in the Middle East, and even though the majority of Jews in Eastern Europe were called Ostjuden, and even though Israel ended up with many Jews from places like Yemen, Iraq, Syria, and Morocco. It would be hard to describe Israel, then, as simply a Western entity. And, of course, this characterization ignores the Palestinians who are citizens of Israel. Even in demographic terms, then, Israel cannot be simplistically reduced to “West,” but nonetheless this equation persists.

SC: To skip to some current debates, it is quite ironic that this political investment of Jews in Westernizing themselves seems to have limits, at least in religious practices. As you know, circumcision is interpreted by some legal scholars and now by a court in Cologne, Germany, as a barbaric ritual that violates fundamental rights of children. So lawyers are using universalistic arguments in order to restrict the religious freedom of parents. Do such conflicts show a limit for this strategy of Westernization?

ES: That is an interesting question because the problem with these debates is that they fragment and fetishize one aspect of a culture, resulting in an ahistorical discourse that is insensitive to the history of colonial domination and Western hegemony. It also becomes a kind of self-righteous discourse that presents itself as acting on behalf of “the universal.” The target of these discourses is obviously what has been seen as “the particular” and those “others” who need to be saved from their particularity. The circumcision debate mobilizes a similar discourse that has been used around the veil. The question is: who represents and acts on behalf of “the universal”? The particular/universal dichotomy often gets enlisted into a rescue narrative.

We cannot forget how colonial discourse often represented colonialism as not simply conquering and exploiting, but also as advancing a universal civilizing mission, rescuing those barbaric people—especially, of course, their women and children—from their own horrible traditions, rituals, and culture. This idealist discourse was framed by the arrogant imperialism that saw itself as bringing light to dark places.

This is unfortunately one side of the Enlightenment. And addressing the intersection of the Enlightenment meta-narrative with colonial discourse does not mean rejecting the Enlightenment in general. The Enlightenment is a complex phenomenon featuring contradictory discourses; what is required, therefore, is to highlight its philosophical contradictions as well as its imperial dark side “on the ground.” In the colonial context, the Enlightenment often meant cultural subordination and psychic devastation. So the question is, what is a “barbaric practice,” and who has the right to determine what is barbaric? Who has the right to say, “I am the savior of these children?” It is not a question of being “for or against” circumcision.

I come from a culture of circumcision, but I would not necessarily see myself endorsing it just because it is my tradition. Apart from the fact that there are Jews and Muslims who refuse to circumcise their children, I object to the way the movement against circumcision has relied on an Orientalist imaginary. I would be disturbed by any kind of state idolatry that would grant the nation-state the power to determine, legalize, and enter the private/community zone of familial decisions and disallow certain cultural practices, under the assumption that “the state knows best.”

Also, especially in contexts of dislocation and alienation, where individuals and communities find it difficult to maintain their language, culture, and identity—as in the context of Germany, where there is little dignified place for Muslim culture(s)—a rejection of circumcision cannot but be interpreted as another form of cultural violence. Such a rejection is inevitably perceived as an imposition of Christian practices, values, and traditions on Muslims. Given colonial history, as well as the persistence of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, circumcision, like the veil, becomes a highly contested signifier. Of course, some might argue that these are not Christian values but just universal secular humanistic values. But humanism can be seen as a sublimated, secularized form of Christian ideas such as providence, salvation, charity, etc. The rescue narrative concerning Muslim children assumes the cultural normativity of Christian children whose Christian background goes often unstated. Yet, all children are born into particular contexts and nation-states, as secular or religious, of a certain class or ethnicity; in other words, every child is born into a web of multiple affiliations, intersecting identities, and potential identifications.

SC: Perhaps, for example, some children are born with a Christian name…

ES: If one has a Christian name, is taken to church as a child, is shaped by certain ideologies, sometimes in a sublimated semi-secular form, one is no less particular than a Jew or a Muslim. So what makes the state the arbiter of which particulars are legitimate and which not? Why is going to a church a more legitimate practice in a supposedly secular state; why is celebrating Christmas and the story of Christ’s resurrection considered acceptable? To resort to a reductio ad absurdum, why should children be exposed to the story of the crucifixion, of nails being hammered into the body of Christ, with all the blood and the tears? One might argue that the crucifixion story is traumatizing for children, and that children should not be exposed to it, and that fact alone would sanction state intervention. It is certainly legitimate to have a discussion about whether or not circumcision is a good idea. The debate is a healthy one, but I am concerned about granting the state, to paraphrase Max Weber, a monopoly on religious violence, especially when state power is wielded in a discriminatory fashion.

Moreover, it is important to recognize that there is a particular burden concerning the history of circumcision in Christian Europe in terms of the role of circumcision in terms of passing and assimilation during the Holocaust and World War II, not only in Germany but in Vichy France. If the authorities suspected someone of being Jewish but passing for a non-Jew, the authorities could check whether the person was circumcised. During World War II, Jewish children who were sent to be adopted by non-Jewish families were warned by their biological parents to “never go to the urinal” in order not to be exposed as Jews. Given the history of circumcision as a marker of identity that could determine life and death, how could we not recognize that circumcision has served as an index of stigmatized religious minorities? In a contemporary context of Islamophobia—where people feel very vulnerable around the denial of their identity, about the refusal of their culture, about the persistent equation of Islam with terrorism—to my mind, any kind of policing of the practice can only be read as a kind of imposition, as assimilation, and even as a kind of cultural violence on the part of the German nation-state. Against this backdrop, violence cannot be read as solely something Muslim parents do to their children, who therefore need to be rescued by the state.

The implicit focus of the circumcision debate has been on Muslims, but what would be the place of the Jew in that discourse? Would the state allow Jews to continue with the ritual but not Muslims? There is a sense that in the wake of the Holocaust, the German state has to be sensitive about offending Jews. But where do we draw the lines about related Muslim religious practices that may be regulated differentially? One is reminded of the French banning of religious insignia, where it was common knowledge that it was aimed at Muslims and not at Catholics (crucifixes, for example), or at Jews (with the kippa), or at Sikhs (with their turbans), or at Santeiros (with their amulets), and so forth.

MB: The debate about circumcision would also be the point where the protests of Muslim communities and Jewish communities in Germany would come together and have come together. Because, there, a politics of coalition emerged where there had long been a dividing line that emphasized the difference between Muslims and Jews.

ES: It is an irony of history, at least of recent history.

Because in recent times, largely because of the Arab/Israeli conflict, there has been a construction in the public sphere of Jews and Muslims as always already enemies. In the media, journalists often appeal to the cliché that “this conflict goes back thousands of years.” But historically that is false; it largely goes back to the late 19th century and the emergence of Zionism. For many centuries and even millennia, Jews and Muslims often faced Christian prejudice together. During the Reconquista, culminating in 1492 and the fall of Granada, the remaining Jews and Muslims were forced to either leave or convert.

Perhaps the Inquisition was the first case of policing by an emerging power—a kind of embryonic nation-state formation. The policing of culinary practices and bodily rituals were part of this religious-cultural surveillance. To investigate if conversion was real, the authorities would check the penises of male babies or children. Another form of policing by the Inquisition was to enter the kitchens and search for colanders. Jewish kashrut (and for that matter Islamic halal) dietary laws require draining of the blood. In Jewish tradition the draining is performed through salting the meat and usually with a colander, allowing the blood to drip out to separate from the meat. Thus the very presence of a colander in a converso house was proof of Jewishness for the Inquisition.

Another marker of Jewish and Muslim identity was the prohibition on eating pork. Could one speculate that the widespread practice in Spain of hanging pork in restaurants, something not found in many countries, was meant as a marker of identity? Does it go back to the Reconquista, where the serving of jamón became a distinctive marker of Christian identity vis-à-vis the Jews and the Muslims?

The two stories/histories of Jews and Muslims are often told in isolation, but in fact the two groups were subjected to the same inquisition and continued to live together within Muslim spaces. The convivencia of Iberia was in fact the norm within Muslim spaces even if unusual within Christian spaces. Jews were invited by the Ottoman Empire in 1492 to settle within its diverse territories. Sephardi Jews in Turkey, Bulgaria, Greece, Egypt, and Morocco, have continued to speak Spanish up until very recently. Yet the dominant view of Jewish–Muslim relations continues the false narrative about an eternal split between the Jew and the Muslim, but ironically this current debate brings to the surface the largely erased Judeo-Muslim history.

In my work, I have insisted on the Judeo-Muslim hyphen, because while the Judeo-Christian hyphen implies a legitimate meta-narrative, the Judeo-Muslim hyphen has been elided. Yet, historically the Judeo-Muslim hyphen could be seen as the norm rather than the Judeo-Christian, which is a relatively recent phenomenon, going back to the Euro-Jewish Enlightenment and reinforced by Zionist Eurocentrism.

Synagogue of Barcelona

Spain has recently issued a call to those who can prove Sephardi ancestry to apply for Spanish citizenship, but has not issued a similar call to Muslims who would also be able to prove their Andalusian ancestry. As with France’s ban on religious insignia and Germany’s circumcision debate, Spain’s policy legitimizes one “Semitic” group but not another within the new European context. In this sense, a de-Orientalization of “the Jew,” as it were, has taken place, but not of the “Muslim-Arab.”

MB: The question of cruelty to animals was also brought into the debates about circumcision in Germany. Opponents on both sides of the issue raised arguments about the idea of pain. I think what is fascinating is that, in order to avoid the question of religion or religious practices, the issues that are raised are those of cruelty to animals, bodily harm, or things that seem not to be related to cultural practice but are rather stigmatized as criminal acts that have been written out of legitimate social practice.

ES: I think it is legitimate to bring out these questions of bodily harm and cruelty to animals. The overlapping dietary laws of Jewish sh’hita and Muslim dhabiha (ritual slaughter) insist on avoiding cruelty to the animal through detailed regulations about the kind of knife used, where it is applied, etc. There can be conversation and argument in the public sphere about whether ritual slaughter is indeed a form of cruelty to animals. Similar questions apply to circumcision: is it a form of bodily harm? It is vital to generate this conversation; but there is a difference between having this conversation and translating it into the state imposing a single point of view. Such an approach does not take on board the burdens of history, does not acknowledge the philosophical dilemmas, and does not face the ways in which prohibiting circumcision is problematic when declared in the name of a pseudo-universality.

*A conversation conducted on September 22, 2012 by Manuela Boatcă, Professor of Sociology and Chair of the School of the Global Studies Program, University of Freiburg, Germany; and by Sérgio Costa, University Professor of Sociology and Director of the Institute for Latin American Studies, Freie University, Berlin. Published in the Culture Section of Jadaliyya, November 18, 2013.

Ella Shohat is Professor of Cultural Studies at the departments of Art & Public Policy and Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies at New York University. Over the past decades, she has lectured and written extensively on issues having to do with Eurocentrism, Orientalism, Postcolonialism, transnationalism, and diasporic cultures. More specifically, in a series of publications, Shohat has developed critical approaches to the study of the Arab-Jew. Her books include: Taboo Memories, Diasporic Voices (2006); Israeli Cinema: East/West and the Politics of Representation (1989; Updated Second Edition with a new postscript chapter in 2010); Le sionisme du point de vue de ses victimes juives: les juifs orientaux en Israel (2006); Talking Visions: Multicultural Feminism in a Transnational Age (1998); Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation and Postcolonial Perspectives (coedited with Anne McClintock and Aamir Mufti, 1997); Between the Middle East and the Americas: The Cultural Politics of Diaspora (coedited with Evelyn Alsultany, 2013, Arab-American Book Award’s Honorable Mention, The Arab-American Museum); and with Robert Stam, Unthinking Eurocentrism (the Katherine Kovacs Singer Best Book Award, 1994; 20th Anniversary Edition with a new Afterword chapter, 2014); Multiculturalism, Postcoloniality and Transnational Media (2003); Flagging Patriotism: Crises of Narcissism and Anti-Americanism (2007); and Race in Translation: Culture Wars Around the Postcolonial Atlantic (2012).

Ella Shohat is Professor of Cultural Studies at the departments of Art & Public Policy and Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies at New York University. Over the past decades, she has lectured and written extensively on issues having to do with Eurocentrism, Orientalism, Postcolonialism, transnationalism, and diasporic cultures. More specifically, in a series of publications, Shohat has developed critical approaches to the study of the Arab-Jew. Her books include: Taboo Memories, Diasporic Voices (2006); Israeli Cinema: East/West and the Politics of Representation (1989; Updated Second Edition with a new postscript chapter in 2010); Le sionisme du point de vue de ses victimes juives: les juifs orientaux en Israel (2006); Talking Visions: Multicultural Feminism in a Transnational Age (1998); Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation and Postcolonial Perspectives (coedited with Anne McClintock and Aamir Mufti, 1997); Between the Middle East and the Americas: The Cultural Politics of Diaspora (coedited with Evelyn Alsultany, 2013, Arab-American Book Award’s Honorable Mention, The Arab-American Museum); and with Robert Stam, Unthinking Eurocentrism (the Katherine Kovacs Singer Best Book Award, 1994; 20th Anniversary Edition with a new Afterword chapter, 2014); Multiculturalism, Postcoloniality and Transnational Media (2003); Flagging Patriotism: Crises of Narcissism and Anti-Americanism (2007); and Race in Translation: Culture Wars Around the Postcolonial Atlantic (2012).

Shohat coedited a number of special issues for the journal Social Text, including “Palestine in a Transnational Context,” “Edward Said: A Memorial Issue,” and “911-A Public Emergency?” Her writing has been translated into diverse languages, including: Arabic, Hebrew, French, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Polish, Turkish, and Italian. She has also served on the editorial board of several journals, including: Social Text ; Middle East Critique ; Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies ; and Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication . Shohat is a recipient of such fellowships as Rockefeller and the Society for the Humanities at Cornell University, where she also taught at The School of Criticism and Theory. Together with Sinan Antoon, Shohat was awarded the NYU Humanities Initiative fellowship for their “Narrating Iraq: Between Nation and Diaspora.” She was also awarded a Fulbright research/lectureship at the University of S.o Paulo, Brazil, for studying the cultural intersections between the Middle East and Latin America. Recently, Shohat has been examining “the question of the Arab-Jew” in conjunction with “the question of Judeo-Arabic.”

http://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/O/bo26304220.html

© Professor Ella Habiba Shohat