Live Encounters Poetry & Writing 16th Anniversary Volume One

November- December 2025

Vestibule, poems by Stephen Haven.

Vestibule

We volleyed white against his pickup.

rushed him as he hawked Sassafras spring

in 5-gallon jugs. Fired a round against

the rag-tag shop he ran from his old trailer.

In blue coveralls, rubber, knee-high boots,

he’d King Billy Goat Gruff out the door.

Our quicksilver leapt its bed where those

wooded paths hit blacktop. He was always

game to chase us. Long elementary

chain-on-tire months, we’d Rambo also

hoods that rang in fishtails. Larger rigs

drummed the kettles of their empty beds.

Jake brakes hissed. Teamsters ditched

the warmth of their cabs: We nimbled the vigil

of all their candles but still they followed,

hunted me all the way through the idyll

of my first college inter-term. One last time

a shock of snow stunned a four-wheel drive.

I fired from a bridge straight down at him.

He morphed into a heat-seeking missile,

thundered beneath the railroad trestle.

Some long-gone trouble hopped the curb,

bit the track, two fat tires spitting gravel,

two thumping against the ties. Crazy Fucker,

I muttered as I looked over my left shoulder.

Yes, I ran. I was afraid of a man who played

chicken with the ghost of a late-night train.

Up the ladder of that 5-alarm fire, nestled

behind a rooftop railing, I peered down as he

swung his ride into the Sahara of that yard.

He eased a scarred silence from cab to ground.

When he looked up to the mute god in me

where he couldn’t see, the dim-lit quad

squared a ring around him. Then he took

some steps with his arms only. Boots and jeans

trailed a groove in the ground behind him.

From his elbows in the one good light

the quiet never broke but it was breaking

Christ-like on the aluminum and the ice.

I had no slight to offer the haunt he suffered me.

In that refracted silence I was fairly sure

deep inside himself a boy cried out.

In the absence of a word, both boys heard.

I wondered where he’d been, if he ever

bludgeoned what bludgeoned him. Then snug

in my twin bed, just as it was always said,

the chancel of sown sin, faithful as the moon,

lumbered from the roof of that white vestibule,

lit a candle in the dorm room dark, hushed,

shushed, watched me as I watched him, and for

the longest time, hawked me from that height.

CERAMIC REPLICA, QUEEN ANNE’S

CHAPEL, MOHAWK VALLEY, 1712

The wire cross thin as a syringe.

Seated at your desk you lean

across it, barely see it, touch

the blinds, leach the daylight in,

the mission your father’s parish

quickened, your eye almost

grazing that miniature tip,

the small, fired clay your father

saved, cherried in the wood

of his last study. You hold it in

one hand, the gray stone, the black

hinged door, Queen Anne’s Chapel,

1712, etched above that entry,

nine white windows split

into quadrants, a silent copper bell

tiny in its still tower. Keeping a low

profile, above the absent call

to Evensong, the wired right angles

of your near miss, a soldered clip.

Unglazed in the bottom of that clay

penciled in your father’s script,

250th Anniversary, 1962, Made

by the Brotherhood of St. Andrew.

The Iroquois grew skeptically near

apples in white flower everywhere.

The Revolution torched them,

harbored in that one burnt mission

dead Brits, dead priests, praying Indians.

Pick your poison, Johnny, pick it well,

Yanks and Union Jacks, hold them

like a gem to the cataract

of your one good eye, then shut

its brother, baby, pray for your

burnt site. How strange

to think you might have been

struck in the lens by your father’s

life-long gig! Each bedside chat,

each shut-in, each drive to teach

literacy in one prison, the devotions

of a life, and somewhere

in the burnt offering of this desk

the legacy of your own

familial touch. Razing that stone,

blood glazed in your father’s mold,

you rub the smoke and mirror

of that show. A gentle ghost

trickles up. You spirit

your way home, wish yourself

a corporate million, soot choking

the flowers near the watchtower

commanding your kitchen.

Somewhere in the potter’s fire

it’s you yourself you must marry

with your one blind eye, the father

you prayed by, this crazed bisque,

the Queen’s saved silver grown

strange and flat, leavened by the stab

of a small gray cross.

The Daily Double

You wake to find the world as it is

and know it to be a heaven. Against your

better disbelief the Earth as it is

and always now will be, and now forever

is again. You know that you have fallen

out of it, and here in your waking,

refreshed in an everlasting lastingness,

insects drill their malarial bills. Heaven is

the long thin oboes of mosquitoes

just as you never wanted it camping in

the Adirondack Mountains. Or else you

wake to a gaggle of geese, snow-white herons

overhead, herring spawning in a creek

so thick you might scoop those scales

in bunches with the cornucopia

of your thin hands. Or Shangri-La takes

you to 105 degrees, the antithesis

of anything that ever sailed

or soldered you. Between the pincers

of your thumb and index, you skewer

deer ticks by the dozens and still

behind one knee dementia buries

its necessary blackhead. You scratch

the concentricity of that target

then wake to the reality of your

absent father in one bare bulb.

Now who will crack your bread?

In a hunger so hot and heavenly

it all seems Earth again, power saws

revolve their circular hymns.

Once again, the early morning shift

hums as you thought you left it

rotting its $3.12/hour in a clock

you punched one adolescent noon

then fled the smell of stale tobacco

lingering forever among the plastic

chairs and linoleum of Building Six.

Now it is your mother who simply

dissolves to nothing again:

She is nowhere in the bone spurs

of your heavenly ankles,

nowhere on the loading dock

where each deathless blast stirs

the insomnia of this daily double.

You watch her picking gravel

from her corned feet, weighing

the pressure behind one retina,

detached from everything

she will never see, one wink

weighing the surgical click

of your scoped-out knee,

your patched hip waiting on

its lost bone, one gnawed metallic

thankfulness, long and round,

your Kaddish, your rosary,

your prayer rug pointed East.

Three Friends

He refused to shovel shit at the home

of his foster parents and would punch

dumb beasts square in the face until one day

he broke his hand. When he turned sixteen

by law they sent him home to the city

where violence marked him, chalked

silhouette shadowing even his absence.

We feared the sudden explosion of his

diminutive frame, as if the dominant passion

of puberty trumped scale, reason,

and the experiment of newly-grown bodies

blossomed its most beautiful barbed flower

in abandon only. Then one night

something happened, I don’t know: Snow

was drifting through one broken window.

Someone named Ross wanted to play

instead of Black Jack, Pinochle. A bottle

smashed against the plasterboard.

Brooks—all five foot four of him—grabbed

an old ax, swung once and twice, so drunk

that all he could do was miss, threw it down

and ran outside into the bloodless snow.

Brooks’s dog ran back and forth. Ross passed

out finally on the couch. I couldn’t stay

and had nowhere to go, so I went out,

along the river, through the sleepless night

all night and nearly froze. When I got back

at noon, Ross cracked a grin: “Where

the hell you been?” It’s a wonder Ross

didn’t kill Brooks then. Brooks just opened

another bottle, never mentioned the ax,

the scattered cards and broken glass.

They bit the hair of the dog that bit them

and laughed and laughed. I drank too.

Huddled in the corner, watching whiskey

help old friends stay friends, I grew older.

And warmer than I’d been that night

sheltering only in the lockkeeper’s doorway

while the frozen Mohawk broke up

and brushed by the long silence

of the Mohawk Carpet smokestacks.

© Stephen Haven

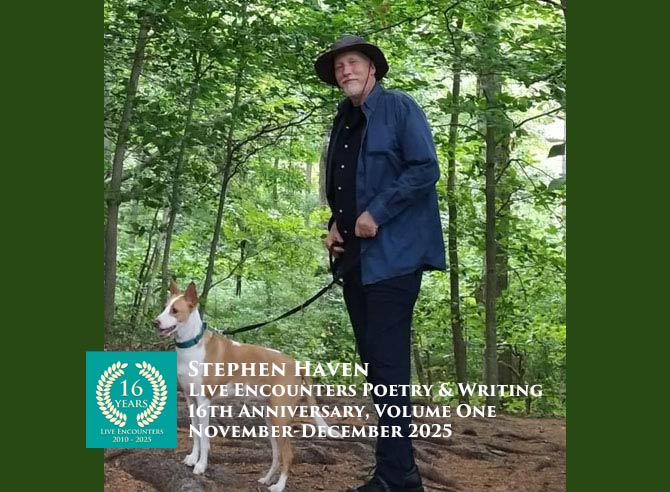

Stephen Haven’s fourth book of poems, The Flight from Meaning, was published by Slant Books in February 2025. In earlier form, The Flight from Meaning was a finalist for England’s International Beverly Prize for Literature. His earlier collections are The Last Sacred Place in North America, winner of the New American Poetry Prize; Dust and Bread, for which Haven was awarded the Ohio Poet of the Year prize; and The Long Silence of the Mohawk Carpet Smokestacks. His work has appeared in American Poetry Review, The Southern Review, North American Review, Image, Salmagundi, Arts & Letters, The Common, The European Journal of International Law, World Literature Today, Blackbird, and other journals. His book-length memoir, The River Lock: One Boy’s Life Along the Mohawk, was published by Syracuse University Press. With Wang Shouyi, Li Yongyi, and Jin Zhong, in 2021 he published the 300-page (Mandarin and English) anthology of collaborative translations, Trees Grow Lively on Snowy Fields: Poems from Contemporary China (Twelve Winters Press). He has received grants and fellowships from the Fulbright Foundation, Yaddo, MacDowell, the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, the Djerassi Foundation, and five Individual Excellence Awards in Poetry from the Ohio Arts Council. https://www.stephenhaven.com/