Live Encounters Books-Reviews Volume Seven

November- December 2025

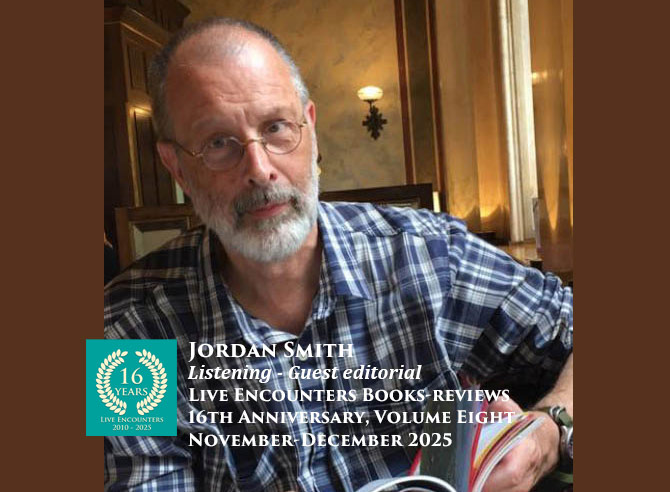

Listening, guest editorial by Jordan Smith.

I’m on my usual walk in the woods near my house, and as usual I have earbuds in place and I’m listening to music. Today it’s an album by a group of Ornette Coleman alumni, Old and New Dreams, a long-time favorite. But today I am also depressed, anxious, angry—why doesn’t matter; you have your own list, I bet—so much so that the music hardly registers. I’m thinking about stopping it and putting my earbuds in my pocket, and that is not how it usually goes.

About a quarter mile into the stand of mixed hardwoods, I’ve gone past the wall of bugs that shimmers at the trailhead, down the steep hill with the little side trail to the ledge where the high school kids hang out, across the creek on the new bridge the Boy Scouts built, half-way up the equally steep other side, turned to follow the trail that climbs the edge of the ridge more gradually, before I actually begin to hear the music. The first cut is Ornette’s “Lonely Woman,” bluesy and melancholy. If I were looking for music to fit my state of mind, this might do it, but that’s neither how nor why I want to hear it. What catches me a minute or so in is Charlie Haden’s bass. Low pulses repeated, it might be the abstraction to near-zero of Coleman’s subtle, complex melody, beautifully articulated by Don Cherry’s trumpet, but I can’t imagine one apart from the other, not in this moment, any more than I can imagine silence without sound, consciousness without the binary oppositions that seem to make it possible. Ornette’s melody is a cry, a woman’s cry, as he tells us in the title. Cherry’s trumpet gives it voice, but a trumpet is not a woman, and we’ve no way of knowing if her loneliness is something he shares, but he inhabits it as she inhabits his horn. And if Haden’s bass is neither, neither is it separable. It is the Tao that cannot be told, it is Thomas’ “the force that through the green fuse drives the flower,” it is Dickinson’s “formal feeling” that witnesses loss but cannot stop for it. A few more minutes into the track, Haden takes a solo, playing the melody with great insistence and delicacy, after a passage in which Ed Blackwell’s low drum meshed so closely with the bass you could hardly anticipate which you’d hear next, a moment of unity, which is presence defined by the absence which it defines. It is beautiful and entirely without sentiment.

I’ve been listening to Charlie Haden since I discovered jazz in my mid-teens. I may have read about Ornette Coleman’s music in Downbeat or in a book by Nat Hentoff, but I first heard one of his records in the listening room of the Rundell Library in Rochester, the massive and elegant building along the Genessee River (on opposite bank was the National Casket Company, whose sign, clearly visible from the listening room, was the subject of a memorable piece of light verse in the local paper, a comedic version of the Buddhist evening gatha about the decreasing number of our days) where I came to check out books I couldn’t understand. If it was avant garde or difficult, I wanted to know about it, if not necessarily to know it. Finnegan’s Wake defeated me. James Merrill’s poems resembled nothing in my life, and the Cantos… When difficulty outweighed pleasure, I hadn’t the chops for it. But that album—Ornette!, with Blackwell, Cherry, and Scott LaFaro on bass instead of Haden—I got right away. Dancing in Your Head Ornette would title another album decades later, and that’s what this early album was doing, especially, I thought, an aspiring trumpet player myself, when Cherry took the lead. The idiosyncratic solos, like good monologues amidst the conversational interplay, the propulsions and provocations and asides. The band wasn’t playing who they were. They were playing an idea of freedom, of who we all might be.

The next cut, “Togo,” begins as a Cherry solo, and then a voice articulates the rhythm. Blackwell joins in on percussion and then it’s his solo, his articulation of the pulse Cherry set up and, as at moments in “Lonely Woman,” the lowest drum fills in for what a bass might do, and it is hard to tell if I hear the bass as there or as absent. I was so locked into Haden on “Lonely Woman” that missing him here is almost as intense as hearing him. I don’t think I would have noticed any of this if I hadn’t been reading Where the Heart Beats, Kay Larson’s study of the influence of Zen Buddhism on John Cage. Larson retells a story that Cage loved to repeat, of his visit to the anechoic chamber at Harvard in search of total silence. It wasn’t there. He heard what the technician said was the low sound of his blood circulating and the high pitch of his nerves firing. This might have been disappointing—where was the silence? Instead, Larson explains, it was liberating, an insight into the way in which all our oppositions are co-dependent, each arising in the midst of our desire for the other. Haden lays out on “Togo,” but if you come to that song after “Lonely Woman,” you can still hear his presence in what he might have played. The next cut on the cd, “Guinea,” opens with another Cherry solo. Cherry’s tone on this album, recorded with the ECM label’s typical clarity and precision, is gorgeous, in need of no electronic enhancement. But the engineer has added a shimmer of reverb at the end of each phrase. He’s there, then he isn’t, but he still is. Then the shimmer becomes Blackwell’s cymbals.

One use of art, Larson quotes Cage as suggesting, is not self-expression, but self-alteration. Listening now as I reach the crest of the ridge where the hardwoods begin to shift towards the pine plantation that makes up the lower part of the park, I’m not so lost in myself; there’s less self to be lost in. Shimmer into something like that glint of cymbals. That possibility: like the music, it’s here and then it’s gone. And then the next song comes on, unexpectedly, T’ Monde’s Cajun version of Huddy Ledbetter’s “In the Pines.” I must have jiggled my phone in my pocket. Happens all the time. The music: here and then it’s gone, just like Mick Jagger sings.

And then it’s not. There are desolation and desperation in “In the Pines,” whether the version is T’Monde’s or Leadbelly’s or Fantastic Negrito’s or Bill Monroe’s or Kurt Cobain’s, that will not leave you when the music stops. If ever a song felt like a curse to be borne, this one is it. And an invitation too. How many versions are there, with each singer taking on the tangling and scraping of a scramble through those dense branches, as if there was another side to come out on. While the order of the verses floats depending on who is singing them, and so does the emphasis—infidelity, deadly labor, desperate love in a desolate landscape—two things persist: the deception that’s staring us in the face and the shiver when the cold winds blow through those woods. Presence and negation dancing. This world we recognize and barely know.

Which is another way of describing poetry, not just poems, but the nature of poetic composition, a subject treated beautifully in Christopher Nicholson’s The Making of Poetry, a study of the early works of Coleridge and Wordsworth that the author carried out by living in the countryside where they’d retreated, visiting their houses, walking their walks, and speculating on just what state of mind they might have fallen into, a way of reading that does honor to the lives and the writing. One step, and then another. One step follows and alters the one that implied its possibilities; one word strikes the empty ground of the page and anticipates the emptiness just coming. I do a lot of writing in my head in these woods, in the hardwoods where the oaks frame the sharp blue sky of an upstate summer, in the pines that cross that same blue in winter, like strike-throughs on a page, elisions that finally make the light clearer, more intense: a shimmer, a shiver where the cold wind blows.

The shimmer is the fear that we can’t hold what moves us most in the splendor of its presence. The shiver is the fear of the nothing that, as Stevens said, we cannot know until we became it. Now that I’ve let the music stop, it’s the poems that accompany me: “The Snowman,” and Dylan Thomas, and Emily Dickinson, the lines of Merrill and Pound that flummoxed me years ago in the library and that I live with now, complicated but companionable. (You’ve got your own list, I bet, and your own playlist of songs.) Marvin Bell’s “I’d have to ask the grass to let me sleep.” Marvin had a habit of interrupting a thought by saying, “You remember that poem by,” and he’d mention a poet, “the one that starts…” He knew I’d come to love Merrill’s work, so on our last visit, out of nowhere, he reminded me of the opening of JM’s “Mad Scene,” “Again last night I dreamed the dream of laundry.” It was his way of acknowledging that we were friends now, who were once teacher and student, and it was no more an interruption than the sudden revelation that comes just before the formulaic conclusion of a tale of Zen transmission, “and then he was greatly enlightened.” And then he was gone, but not, because see what I have remembered here between the hardwoods and the pines.

© Jordan Smith

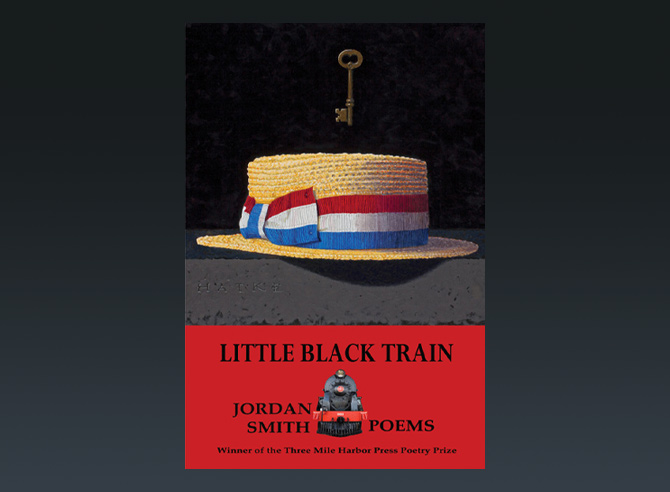

Jordan Smith is the author of eight full-length books of poems, most recently Little Black Train, winner of the Three Mile Harbor Press Prize and Clare’s Empire, a fantasia on the life and work of John Clare from The Hydroelectric Press, as well as several chapbooks, including Cold Night, Long Dog from Ambidextrous Bloodhound Press. The recipient of fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim and Ingram Merrill foundations, he is the Edward Everett Hale Jr., Professor of English at Union College.