Live Encounters Poetry & Writing 16th Anniversary Volume Four

November- December 2025

At Grass, guest editorial by David Rigsbee.

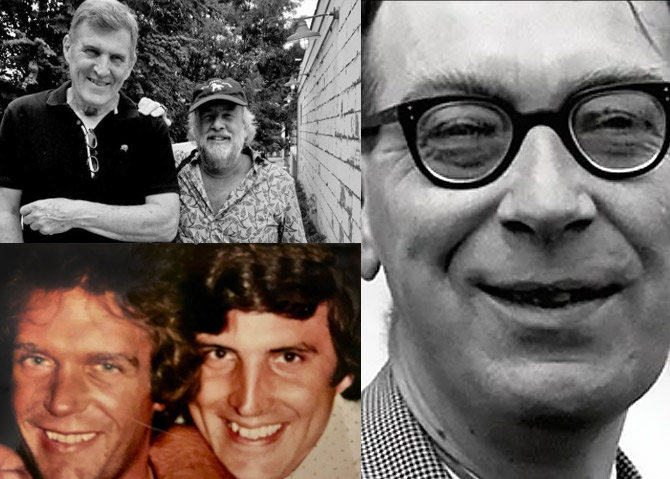

David Rigsbee and Michael Waters, ca. 2016. Photo courtesy David Rigsbee.

Philip Larkin. Photo credit: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/blog/philip-larkin-life-art-and-love/

There’s a poem by Philip Larkin that bears on plight of poets as they age, using racehorses as its conceit. The poem begins by showing us two thoroughbreds at a distance. They belong to a breed that once won famous races and now fifteen years later stand anonymous in a field. Larkin doesn’t present this as diminishment. The shift from “the starting-gates, the crowd and cries” to standing “at ease” in pastoral anonymity feels like a kind of earned peace, even dignity. It asks: what if the aftermath, the quiet aftermath, has its own validity? He then explores the ramifications and raises an issue that has been on the minds of my poet friends and me.

On July 4th of this year, I went with my old friend Michael, an accomplished and prolific poet, to the beach at Asbury Park, New Jersey. He joked that we could swan our way in Speedos down the famous boardwalk and sink into the beach sand in our aluminum chairs. Michael had always been an encyclopedic historian and aficionado of rock music. I once asked him if he remembered the group who sang an old tune from my junior high days, “Denise,” and in a nanosecond he shot back: “Randy and the Rainbows!” That was their hit, and they never charted again. On this day Michael supplied us with baseball caps signaling his fealty, and now mine, to The Ramones. It was like accepting a communion wafer. Of course what turned up were two poet dudes in their seventies, regarding the families and children strolling by, and occasionally looking out to sea, but also reflecting on the recent deaths of such poets as Stephen Dunn, Michael Burkard and Gerald Stern, all of whom we knew, and of the ailments of others within our range: failing eyesight here, the onset of dementia there, maladies as varied as gout and cancer.

Michael and I have known each other over half a century, and in this fact alone, our experiences took on their own kind of rhyme scheme: teaching, lovers, wives, children and grandchildren, shared books, emergencies and all manner of existential changes. It was Bergson who reminded us that time was something more accurately felt than marked. We also talked about oeuvres and careers, who was still at work, who survived, even thrived, who could write and perhaps more tellingly who never learned how to, who were self-blinded and who merely odd, like toadstools persisting in plots of basil.

The poem acknowledges that “their names were artificed” to be “inlaid” in memory—but the horses themselves seem indifferent to whether anyone remembers. They’ve moved beyond any need for recognition, if indeed they had this need in the first place.

Their status now might offer a complicated consolation: the races mattered in their moment, aroused enthusiasm, fan loyalty, and the spectacle of energy and mastery at work, just as (it is implied) a poem promised aesthetic pleasure, shaped sensibilities, and invited imaginative participation, etc. Whether that poem goes on to be known by successive generations should not be confused with its intrinsic value. Or so this line of thinking goes.

In Larkin, the horses stay together; they “shelter” each other. There’s something about shared experience, mutual recognition among those who understand what the others have been through. In my circle of poet friends we know each other’s work and share reference points.

The web of recognition and understanding has its own completeness. As for the lure of ambition, it should be noted that the horses once had greatness “flung” over them—in other words, it was imposed. Now they possess time differently, inhabit their lives rather than being driven through them. As for us, we had our entire poetic training—as had the generation before us—built on the assumption of continuity. The implicit promise was that this transmission would continue: our work would enter a similar stream, be available to future poets in the way those voices were available to you. But what if that model of literary time is dissolving? It’s not through anyone’s failure, but through genuine historical shift—the sheer proliferation of voices, changed reading practices, different cultural priorities, the fragmentation of any shared canon.

This is where “At Grass” turns philosophical. The horses don’t know they’re forgotten. But we do—or at least we’re contemplating that possibility. So the question for me becomes: can you choose the horses’ condition? Can you actively embrace making work whose primary justification is not its future reception but something else entirely? What would that something else look like? Well, there’s the satisfaction of the making itself—the problem-solving, the music, the craft involved in capturing something true about experience, regardless of the audience. There’s the sharing of allusions and standards, such as I find in the wide net of Americana that so many of the poets roughly my age can never seem to exhaust. And yet (and Randall Jarrell, himself turning up on few reading lists, remarked that “and yet” was a proper next move to almost any observation) here’s the other thing. Poetry isn’t private meditation. It’s an art form that assumes

communication and connection. A poem without readers isn’t quite complete as a poem. So there’s real loss in imagining your work becoming inaccessible to future practitioners. Maybe the tension is irresolvable; which might be why “At Grass” proceeds with an image of the horses simply standing and looking on, not transcending their situation but inhabiting it. It’s not consolation exactly, but a kind of earned equilibrium it surely is.

So what started out as my memory of discussions I have had with my poet friends and the feeling that our time and our own favorite poems from the previous generation have been superannuated becomes an accounting of a deeper sort.

This isn’t a pity-party. It’s a thing, and I want to think of it in terms of poets who have passed on and those who are about to. Larkin’s poem, by a less circuitous way than it would first seem, reminded me of the death of an aunt of mine from 40 or so years ago. She was the oldest member of my mother’s large, hardscrabble farm family in the south. She was more cheerful than she had cause to be, having lost her only son to an early stroke (he was also hobbled by polio) and her husband, who succumbed of Lou Gehrig’s Disease. What I thought of was the manner of her death: a stroke that yanked her from life and left her wedged between the refrigerator and the kitchen counter. Larkin feared a similar death, of being wedged between a radiator and a bookcase. And that was in fact how he died. My aunt’s death both mirrors and rhymes with Larkin’s. She had no poetry in her, but who is to deny a connection between private mortality and cultural passing?

As for Michael and myself, it was a good day. We passed the legendary music club The Stone Pony on the way back to his car. I was sunburned, but I added to my store of trivia the fact that that Blondie and Sam & Dave had been among the stars who over the years rocked the same stage as Springsteen. Michael also explained that Randy and the Rainbows’ single 1963 hit, “Denise” had been gender-flipped by Blondie and went on to become a massive international hit (“Denis”) in 1978. I don’t know if Larkin himself ever himself experienced being “at grass.” I suspect not, any more than my aunt did. The poem concludes, however, quietly and majestically with the image of the horses being led by “only the grooms, and the grooms boy/ With bridles in the evening come.” They’ve had their race, whether they knew it or not, and the track has long been raked smoothed again.

Still, something in us stirs when an old poem reenters the air. A line brought up from memory, even a half-forgotten one, still carries a vestigial sound, the background noise, of the years it has traveled. The past, it seems, is not behind us but grazing nearby, head down in the long grass. Perhaps that’s what it means to outlast one’s moment—not to remain visible, but to remain available. The field doesn’t notice who’s famous; it only receives what comes to rest there.

© David Rigsbee

David Rigsbee is the recipient of many fellowships and awards, including two Fellowships in Literature from The National Endowment for the Arts, The National Endowment for the Humanities (for The American Academy in Rome), The Djerassi Foundation, The Jentel Foundation, and The Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, as well as a Pushcart Prize, an Award from the Academy of American Poets, and others. In addition to his twelve collections of poems, he has published critical books on the poetry of Joseph Brodsky and Carolyn Kizer and coedited Invited Guest: An Anthology of Twentieth Century Southern Poetry. His work has appeared in Agni, The American Poetry Review, The Georgia Review, The Iowa Review, The New Yorker, The Southern Review, and many others. Main Street Rag published his collection of found poems, MAGA Sonnets of Donald Trump in 2021. His translation of Dante’s Paradiso was published by Salmon Poetry in 2023, and Watchman in the Knife Factory: New & Selected Poems was published by Black Lawrence Press in 2024.