Download PDF Here

Live Encounters Magazine April 2023

The City: Inside the Mind and Outside

by Professor Ganesh N Devy

The most remarkable foundation of the city as a sociological institution is that it is profoundly ‘anti-national’. One is not describing here the city as a traitor, or as ‘a criminal in the eyes the given national code of law.’ What is meant here is that the historical process of the formation of nations –the nation as a political institution—has been very different from the historical process of the formation of the city as a sociological institution. The nation is an expression of the human race to bring many under a single and well defined space. The city, on the other hand, is the expression of the desire to bring one into many chronological orders.

“God made country, man made the city,” was perhaps the most popular line in the intellectual discourse of the eighteenth century, particularly after the heart rending scenes of migration fore-grounded by the literary works like Oliver Goldsmith’s The Deserted Village fired poetry and paintings born out of what the contemporary German philosophers termed the esamplastic imagination. The entire ‘Romantic’ generation of philosophers, painters and poets of France, Germany, Spain, Italy and England shunned the idea of having to create urban settlements. The copious paint brush of Turner, for instance, did not have a single stroke to spare for an urban dwelling or street, though the children there were as innocent as the ones in the villages.

If William Blake did speak of those children, as did Charles Lamb, it was to frighten the reader off the specter of the sinful existence that a city has in store for the rural migrants. Rousseau’s call for a return to Nature, though too late in the economic history of the colonial west, was found alluring by the pre-Marxists, the Romantics, the Symbolists and even the Pre-Raphaelites for a whole century. The idea of a city, despite its theatre and the tantalizing possibility of not only philandering but actually ‘making it’ by accepting the status of a ‘perpetual picaro’, took a fairly long time to rise out of its stigmatized status as a den of sins.

The adolescent heroes of Charles Dickens, the fascinating heroines of Flaubert and indeed the savage drama at the heart of the Beggars Opera, all point to how harshly the city was considered by the social ethics of the first two centuries of the Industrial Revolution. And indeed, those were the cities whose entrances were adorned by the docks crowded by the amorous sailors, crammed with ever narrowing lanes made heavy by houses rising to full three stories of height, obscuring the clear view of the cathedral or church, with back-doors opening into deep-cut gutters, covered but with manholes that made night journeys of burglars and criminals look like an adventure. The city as understood in those times, in short, was squalor.

To make a city beautiful, long winding paths to the country had to be dug up by cutting small hills. These long paths, initially built for horse carts and hansoms alone, and the bridges built to span the port side rivers allowing the thoroughfare between the citizen girls and the voyaging sailors, brought to the European cities for the first time a look, albeit a false look, of being seamless. Otherwise, of course, the cities giving rise to what Karl Marx called ‘the capital’ were condemned to be prisons created by the landless and rootless for themselves in an attempt to become the merchants of avarice.

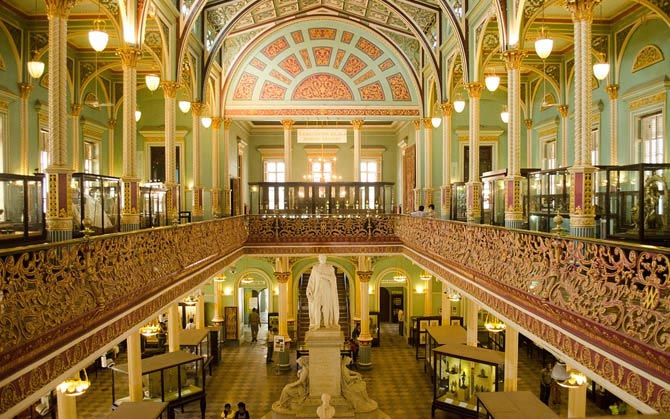

Of course, there was a saving grace in the form of the Royal silver line added to the low-market city shape, such as the Versailles and Buckingham Palace, for instance. But, really speaking, they belonged to the medieval period. Their beauties were born in Baroque or Gothic nurseries, their sinews built of arches and pillars coined in the idiom of Faith, just as the mosques in Spain and the forts in India were created on the foundation of theology rather than a pure unambiguous statement of pride and power as a present day Twin Tower in NY is.

It is not, of course, that the palaces were placed out of the cities; rather it was that the cities were spaced away from the royal enclosures, at least in the case of Paris, London, and Vienna. Rome was a bit too old to have received this unique urban planning feature, and it had already lost the city throb to the grand old Vatican. In Italy, of course, many other things happened in an anachronistic manner. Cities like Siena had already brought the entire citizenry within the fold of its peculiar royal splendor, drawn more out of the natural element than out of a divine sanction (as the political systems in other European countries liked to formulate). One has to understand that the Italian cities had perhaps to build themselves as –anti-fortresses to the Papal charm. The Diamond Palace at Brussels and the sun-dial in Bologna have a similar genesis.

Quite opposed to this, the world famous Las Rambles avenue of Barcelona, throbbing with licentiousness and energy such as only the Spanish language can express, was already established two centuries before the Industrial Revolution got under way, and even remotely dreamt of disturbing the pastoral glow and warmth of Spain. As a price, perhaps, the post-Revolution Barcelona had to keep tearing itself from the hustle-bustle, and keep climbing above the mean sea level as far as it can. In a sharp contrast to the English, French and the Dutch cities, the American cities are built differently. Even if the linguistic idiom forming the basis of their creation is drawn from European languages, the ‘imaginary’ fuelling their growth is deeply rooted in what the expression The American Dream symbolizes. They are racing as if it were to challenge the idea of horizons. Limits, what shit! They seem to say.

The force and the ferocity of the idea of city as the hub of civilization as forged in the self-absorbed and aspiring American city provides today the moving inspiration for a Hong Kong and Dubai. They are built as if the human civilization did not begin at all until the automobile came into existence. There is also another variety of the urban ‘grandeur’ interpreted literally as meaning big and bold. That is to be seen east of the now non-existing wall of Berlin. One is not, of course, thinking of the grand Chancery building or the Berlin University. They were very much a product of the surpluses produced by the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

But the central quarters of Moscow, and similarly of Beijing, have on show this grandeur. It occupies too much space. The quadrangles and court yards of their own agrarian past – in China’s case made tranquil by the Buddhist philosophy, came to be re-presented there after the revolutions in terms of “The Lord Alone Is True”, even the statues placed in these vast spaces were created quite clearly to intimidate and to silence the viewers. One never had the courage to ask ‘who, where and why?’ While trying to keep them in view within a single pair of eyes – as one could does while looking at the pietra dure of the Medici style, or just the amazing Michelangelo jobs.

Though the ancient past is a bit too forgotten unless it belongs to the affluent nations, Timbuktu too should be a model one needs to bring in the discussion of intelligent cities. Damascus and Kabul are the other names. Alexandria, of course, needs a major place in the list, both for its intelligence as a city as well as its irrevocable place in the history of the ancient as well as the modern world. We know very little of Manchu Pichhu, at least not as much as Pablo Neruda did, and the mythical Troy is not really accessible to us in terms of the usable ideas for creating and nurturing cities, even if it could set on sail a thousand ships of warriors at one time.

Relatively, more accessible are the ideas that were shaped in the colonial times. Kolkata and Mumbai, and their numerous younger and feeble siblings, quickly learnt that the Cantonment as the heart of the city must be kept outside the city, for security and authority. Though Sydney and Perth, easily far more intelligent than Chicago, they somehow carry clearly the mark of being the frontier cities coming up, in their case, the wide ethnic world of the southern hemisphere. Both Boston – still a lovely memory of the homelands across the ocean—and Washington, a city burdened with the responsibility of disciplining and civilizing the world, manage to look at the first glance a little untypical of the American idea of ‘monstrosity’ as a museum of beauty, they soon reveal their identities to the second time visitor.

So varied are the philosophical, ideological, artistic and cultural roots of the cities spread over the world that it is just impossible to offer a single definition of what a city really means, except that it is a place that holds too many in too small a space. But the hinterlands in many African countries, in Latin America, in Goa or Kerala show that the law of too many in a continuous space is not enough for the definition of city. These areas have hundreds of miles of non-ending rows of houses all along the drive ways and yet the local people do their cartography in terms of ‘adjacent villages’, not as a city. The density of population per square kilometer or mile, too, is not so much of a useful definition.

For thousands of pilgrimage places, the variable density as well as the constant density of population p.s.m. can be much higher than that in the very heart of the most populated city like Tokyo, Mumbai or New York. These, or any other quantitative measures such the per capita consumption of energy, food, consumable goods, bank savings, borrowings, schools available, medical facilities, or jobs/unemployment levels, do not seem to serve the purpose as the exceptions one cite far outnumber the norm sought to be set.

I heard in a recent conference held at Evian in France that a city is essentially a transportation hub. The argument was put forward quite energetically. I did not present the case of the Ambala camp or Panvel in Maharashtra that far outdo the neighboring Chandigarh and Pune, respectively, in term so of the ‘transport density’ but are not acceptable as cities at par with their more distinguished neighbors. The subtle relationship between Zurich and Geneva in Europe, or between Montreal and Vancouver, or for that matter between Agra Road and Delhi need to be considered with all nuances to understand why ‘transportation’ density can never be the measure for a location being a city or not.

If these quantitative parameters are not so good to define the unique formation that a city is, what would be the best alternative to finding its defining features? If the special scales do not yield results, can the temporal scales help? Perhaps they may, but in a limited way.

If we propose that a city is a place that brings the past and the future in a union, makes both permeable, manages to evolve an idiom of translating one to the other, we may be able to bring many of the world’s numerous cities under this single definition. These, for instance, can include Delhi, Shanghai, Vienna, Paris, Madrid, Venice, Tehran, Lhasa, Antwerp, Edinburgh, London, and a long list of such others. Indeed, it has been the greatest among the accomplishments that the city as a medium of history has to its score that it allows modernity to flow out the local tradition, that it enables modernity to be grafted successfully on to the tradition.

The only problem with this definition is that the combat and collaboration between tradition and modernity can be witnessed taking place with the same degree of intimacy and animosity in the smallest of the human habitation. Every primer of Anthropology will tell us that even among the most traditional among traditional societies, and among the smallest among the small indigenous groups, the tension between modernity and tradition plays itself out in precisely as numerous ways as in larger places and populations.

Perhaps, rather than pointing to the dialectic between the traditional and the modern, it may be closer home to maintain that the city has a greater capacity to hold the two together without one destroying the other completely. One may even say that the city holds within itself many times, that it is not just a diachronic companion to the human soul, but a poly-chronic sustainer of the human spirit of quest. When a city blocks one or many levels of time existing within it, it slowly starts dying as a city. The ones that insist on keeping all of their ‘traditions’ entirely ‘unsullied and pure’ start ossifying and end up being ossified on their own volition.

Not all cities in the past have gone down only because of being surrounded by or destroyed by what the Latin term describes as ‘barbaric vernaculars.’ Most spell out the demise by closing their minds. The two most known examples of this and celebrated in imaginative literature are the ancient Troy and the twentieth century Oran as in Albert Camus’ The Plague.

They first closed its gates to all possibilities of ‘combat’ as indication of the destruction; the second sealed its borders as a cure for its inner infection. London, prior to the great fire was getting close to this condition; but decided to open up after the calamity – though the significance of the shifting of the theatre space has yet to be fully stated—and London laid the foundation of its status as the perpetual City. Similarly, it is the vicinity of Long Island to it, a place where the refugees could find a safe haven that should be seen as the great source of the New York Tradition. But these instances are merely from the perspective of social or spatial composition.

It is those cities that allow many Times to live together within its spaces that alone ensure their sustainability. A city, in other words, has to be chronologically eclectic. Such eclecticism enables it to provide spiritual solace to a larger sociological, ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity, particularly so since the city is a non-theological formulation. This should also provide us clues to measuring city-fatigue or city-stress. The stress arising out transportation mismanagement can, perhaps, be cured by innovating transport technologies; but the city-stress caused by elimination of one or several levels of time from its life styles, habitation patterns, speech rhythms, visual forms, can hardly be reduced or cured by any innovation in technologies.

Why television has not succeeded in reducing that stress in any city is a question that urban architects must closely study. Similarly, what was it in the city of Dublin that compelled all outward migrants to maintain their links with the city, while a similar behavior is not seen in relation to either Manhattan that looks mono-chronic or Madurai that looks, but at the other end of the spectrum, equally mono-chronic, is something that we need to understand well.

A city becomes sustainable only if it learns to live in many times with an equal degree of ease. In India, the phenomenal and completely unpredicted growth of Delhi is a result of Delhi’s ability to be historical, contemporary and futuristic at one and the same time. On the other hand, a mighty medieval capital like Champaner went down like nine pins because it remained obsessed with the present alone. It blocked itself from the past that sat aloof on top of the Pavagadh hill, and the future that was spreading out in the plains of Ahmedabad.

In contrast, when Ahmedabad replaced Champaner, it survived as a thriving city for four centuries even when dynasties came up and went down, different industries and livelihood patterns came up and went down. Put very simple, the cities without sympathy for the past and a sensitive and friendly eye for the future, really, have no present as well.

The most remarkable foundation of the city as a sociological institution is that it is profoundly ‘anti-national’. One is not describing here the city as a traitor, or as ‘a criminal in the eyes the given national code of law.’ What is meant here is that the historical process of the formation of nations –the nation as a political institution—has been very different from the historical process of the formation of the city as a sociological institution. The nation is an expression of the human race to bring many under a single and well defined space. The city, on the other hand, is the expression of the desire to bring one into many chronological orders.

Seen from a purely pedestrian point of view, a given city invariably forms a part of one or the other nation. Any city is bound to have its political affiliation and in that sense it belongs to nation. But while cities thrive on their ability to host diversities, nations prosper because they succeed in bringing people under a common or shared code of political and legal norms.

Perhaps, the human race has an innate (genetic) inclination towards fostering diversity. Therefore, the nation as a political institution has been relatively short-lived than the city as a civil institution. In history we have numerous examples of specific national identities having gone down, whereas the cities within those nations have continued to exist, survive and even thrive.

This has been the world’s experience during the worst of the wars. In some cases, when the houses, buildings, markets and temples in a city have been plundered and destroyed in a war, the city itself—its sense of being itself—has remained undestroyed. Thus, one need not look at the city as a sub-set of a nation, though the political maps as of now beckon us to do. Similarly, the city need not be seen as a ‘scaled up’ village. The village-city-the state is a false hierarchy arising out of various historical coincident.

It is because the city as an institution is not of the same family as the institution that nation is, cities constantly strive to open dialogues with many cities, many nations. This dialogue is never of conflict, confrontation or collaboration. It is invariably the dialogue related to assimilation, transfer, and transactions. In other words, the nation is a text; the city is its constantly renewed translation. And like a typical translation, the city has two idioms, one close to the idiom of its original location, and the other close to the idiom of its receiving audience. Here, of course, I speak in metaphor and not in the literal sense of the term ‘idiom’.

I am thinking here more the idiom of being, the existential consciousness which enables the phenomenology of entanglement. It is therefore that though the city is not the producer of natural products, it is the mother of all fashions. The city knows how to name human aspiration, how to translate it into reality and how to translate at the same time the commodities from the real world into a new language of aspirations. In this work, the city remains engaged quite remorselessly. Therefore, the city is not a ballad for patriotism; it is an epistle for existence. That is the second most important reason why all cities I have been through have become me.

Every time I have moved into a new city, it has primarily been moving into a new dwelling. The houses I moved into in different cities were either better than the other houses there, or worse than them. They were never just houses by themselves. Moving into a new city was always moving into a new competitive space. In those houses, there were things that were necessary to make life possible, and I did not make any of those by myself. The shapes and sizes, the textures and styles, the functions and utility of those things were all designed by other people, elsewhere.

I merely found myself surrounded by those objects, with my existence incomplete without them. Thus, moving into a new city was always moving into the time and space made by others. In a way, this was to remain an unfinished being, an incomplete becoming. No, not my mind was complete in itself. It brought with it to the new city layers of memory, of many times. But the space remained the same. It was the space that plunged me into a competitive space where I arrived to realize how incomplete I was.

This was always a sure recipe for feeling alienated. In that alienation, I was a beast of burden carrying many times in my memory, and carrying them into the same space. So many cities passed through my life, but the space I found in them was the same. I could escape that space only if I entered the crevices of those cities, found the forgotten people, entered their consciousness and started looking at the world through their eyes. When that happened, I could find myself, felt a little less unfinished, incomplete, continues with the rest and not broken away from them.

The elephant people in Baroda, the Gypsies in Leeds, and the Kanjar-bhats in Kolhapur were all such people who joined for me one layer of time in my mind with the other scattered layers of time, extended my space confined to my cluttered dwellings out towards those wandering feet in the streets. When that happened, I thought, at least momentarily the space and time in which I lived became one, neither retaining their identity, both together they were my ‘spots of time’, allowing me to see myself in the mirror of the world around me. At all other times, and in all other places, I was blinded by the distance between the city space and my time.

© Professor Ganesh N Devy

Professor G. N. Devy, was educated at Shivaji University, Kolhapur and the University of Leeds, UK. He has been professor of English at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, a renowned literary critic, and a cultural activist, as well as founder of the Bhasha Research and Publication Centre at Baroda and the Adivasi Academy at Tejgadh. Among his many academic assignments, he has held the Commonwealth academic Exchange Fellowship, the Fulbright Fellowship, the T H B Symons Fellowship and the Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship. He was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award for After Amnesia, and the SAARC Writers’ Foundation Award for his work with denotified tribals.

His Marathi book Vanaprasth has received six awards including the Durga Bhagwat memorial Award and the Maharashtra Foundation Award. Similarly, his Gujarati book Aadivaasi Jaane Chhe was given the Bhasha Sanman Award. He won the reputed Prince Claus Award (2003) awarded by the Prince Claus Fund for his work for the conservation of craft and the Linguapax Award of UNESCO (2011) for his work on the conservation of threatened languages.

In January 2014, he was given the Padmashree by the Government of India. He has worked as an advisor to UNESCO on Intangible Heritage and the Government of India on Denotified and Nomadic Communities as well as non-scheduled languages. He has been an executive member of the Indian Council for Social science Research (ICSSR), and Board Member of Lalit Kala Akademi and Sahitya Akademi.

He is also advisor to several non-governmental organizations in France and India. Recently, he carried out the first comprehensive linguistic survey since Independence, the People’s Linguistic Survey of India, with a team of 3000 volunteers and covering 780 living languages, which is to be published in 50 volumes containing 35000 pages. Devy’s books are published by Oxford University Press, Orient Blackswan, Penguin, Routledge, Sage among other publishers. His works are translated in French, Arabic, Chinese, German, Italian, Marathi, Gujarati, Telugu and Bangla. He lives in Dharwad, Karnataka, India. https://gndevy.in/