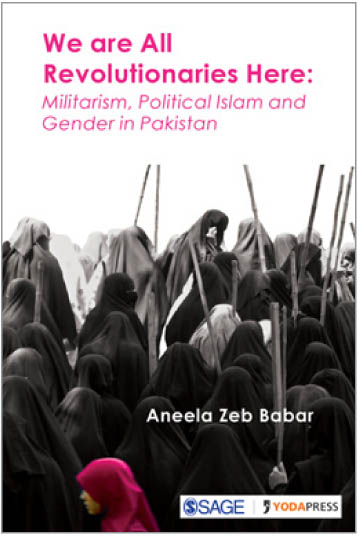

We are All Revolutionaries Here: Militarism, Political Islam and Gender in Pakistan by Aneela Zeb Babar

Published by SAGE Publications. 2017 / 196 pages /Hardback: Rs 695 (9789386062482) / SAGE Yoda Press

Aneela Zeb Babar is a researcher and consultant working on Islam, gender, migration and popular culture. Over the past eighteen years she has been pursuing a career within the academic, research and development sector being employed with universities and non-governmental and international developmental agencies in South and South-East Asia and Australia. She has a strong track record in advocacy of development, governance, gender and cultural issues.

Excerpt from Chapter: On Gendered Spatial and Ritual Politics in Canberra and Islamabad

Excerpt from Chapter: On Gendered Spatial and Ritual Politics in Canberra and Islamabad

The energy created by the ‘living room lectures’ and the introduction of new ‘moral communities’ had formed tensions as prescribed roles through- out the Canberra Pakistani community were changing. The ‘transnational gendered religious networks’ had also struck at what Rahman has declared as the ‘secularist cliché’ that religion be ‘relegated internally to the position of a private creed’ and ritual, as ‘being something merely between a man’s heart and his God’ (Rahman, 1984: 227–28). The challenge of pursuing modification in practice and rituals, while not outright confronting familial structures, has been prominent in the years the dars congregations gained popularity. This is true for other Pakistani communities around the world as well who find themselves in the new political, economic, and cultural settings of the West.

Has the element of cyber–consciousness introduced through Al Huda’s ‘online congregations’ contributed to the ways women now maintain and expand the transnational networks in the Pakistani diaspora? The globalisation of religious information and images through Al Huda-sponsored networks had contributed to a state of affairs where sharing the same geographical place, or any of the controls and restrictions over the mobility of women did not matter anymore. Through advances in telecommunications, through sharing and mastering these networks, women were able to build their own coalitions and find support structures that might not have been available to them earlier under the traditional class and power divisions of the Pakistani diaspora. What is particular about these alliances is their gendered nature, and the consequent reaction in Canberra’s Pakistan ever since these new groupings have gained a prominent profile emphasising that. The energy created by the ‘living room lectures’ and the introduction of new ‘moral communities’ have given rise to tensions as prescribed roles throughout the Canberra Pakistani community are seen to be changing.

What is problematic for Al Huda critics is the constant calls of Hashmi and her organisation ‘to homogenize the structure, religious behaviour and responses of women’s groups so to enforce a rigid Islam’ without allowing any space for the diversity of cultural and ethnic belief that had characterised how Pakistani women had interacted with Islam earlier.

I found much of the Al Huda discourse worrying especially when I read about Hashmi describing the 2004 earthquake in Kashmir and NWFP as God’s punishment for ‘immoral activities’. According to Hashmi, ‘The people in the area where the earthquake hit were involved in immoral activities, and God has said that he will punish those who do not follow his path.’ Opinions such as this are problematic considering the Al Huda Foundation had turned its attention towards the education sector in the earthquake-devastated region of Northern Pakistan hoping to redress the void created by the collapse of government schools (International Crisis Group Report, 2006).

This brings me to another feature of the Al Huda discourse that made me nervous about being part of the congregation. I fear that over time Al Huda would enforce a ‘uniform guide’ to religious interpretation that does not allow any competing discourses. Did Hashmi’s lectures becoming the ‘one truth fits all’ remind me of all that was troublesome about religious belonging in Pakistan during my childhood years? Growing up in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, my neighbourhood friends and I had discovered that we recited our evening prayers differently from each other. When I went to my grandfather who had taught me my prayers, and was the ‘wisest person about religion’ we could think of, he tried to simplify sectarian and ritual differences between us by stating the fact that ‘my neighbours are Punjabis’. That seemed adequate to my friends and myself, and their longer prayers could be slotted somewhere alongside other facts like why they could tolerate spices, could watch TV long after my bedtime, and spoke better Urdu. There were no winners or losers about who prayed correctly, and we were at peace. Maybe when they went back home, their parents might have deplored my family’s religiosity. But during the short period of religious fervour of our school years, whenever we prayed together after evening play time we were comfortable with our differences. Years afterwards, when I narrated this episode to colleagues at university, they weren’t so tolerant. Times had changed, they said, and wouldn’t it be more prudent for me to harmonise my prayers with theirs, ‘for I did want to be a good Muslim, right?’ Maybe it was around this time that I stopped praying in front of others, as I was getting tired of being corrected constantly. Roughly around the same time I withdrew from engaging in what Pakistanis call ‘drawing-room debates’ over my religious beliefs. I had resigned myself to the discomforting knowledge that terms like Islam and Muslim were neither straightforward nor without controversy, so it was best I kept quiet rather than antagonise my friends’ parents. It is this that kept me hesitant to participate more actively in the women’s congregations in Canberra.

I was reminded of this episode when I read Rushdie’s personal debate on his relationship with Islam:

I am not a Muslim, that’s what you meant. No supernaturalism, no literalist orthodoxies, no formal rules for you. But Islam doesn’t have to mean blind faith. It can mean what it always meant in your family, a culture, a civilisation, as open-minded as your grandfather was, as delightedly disputatious as your father was, as intellectual and philosophical as you like. Don’t let the zealots make Muslim a terrifying word, I urged myself; remember when it meant family and light….I reminded myself that I had always argued that it was necessary to develop the nascent concept of the ‘secular Muslim’, who like the secular Jews, affirmed his membership of the culture while being separate from the theology…. I told myself, you can’t argue from outside the debating chamber. You’ve got to cross the threshold, go inside, the room, and then fight for your humanised, historicised, secularised way of being a Muslim. (Rushdie, 1991:435–36)

It made me nostalgic for a time when I too was comfortable with being Muslim, when I didn’t have to be apologetic to my neighbours about my family’s particular ‘ethnic relationship’ towards being Muslim. However, if I was so eager to reclaim this lost relationship, wasn’t it time that I too started grappling with the contentious issues of differences within our religious faith? I am glad I started this process, for I realised quickly that for some time I had my own prejudices and stereotypes about Muslim women, the same ones that others are so familiar with. Over the months the picture I had in my mind was at odds with the actual fears and hopes, anxieties and aspirations of the Pakistani women. These women were challenging the assumptions that, if they were treated as equal members of the community, the community would risk erasure due to a loss of difference from the ‘conquering other’. Why has it been that Muslim women continue to be perceived as passive members of a monolithic community sitting morosely apart, when they could very well be active participants in multicultural cultures whose perspective they too shared in their daily lives? My interviewees took their commitment to Islam not only as one among many moral and spiritual values, but also as something which was itself interpreted and exhibited differently in their relationship to Canberra society. However, what worries me is whether Pakistani women’s connection with Al Huda would gradually move them away from the ‘multiple dialects’ they spoke of culture, ethnicity and politics to one of a single language of belonging and interpretation. This plurality is what I fear we will miss.

However, I hope one’s endeavour to explore a history of Pakistan with the Pakistani women as narrator would not only identify a different gender, but also a new generation and class of interpreters for Islam. There had been a growing need to document the experiences and instances of resistance, solidarity and agency disseminated through alternative voices, activist movements and channels in the transnational and regional forums, those that have remained sceptical of hegemonic discourse. The experience of diaspora had encouraged and facilitated the process of Pakistani women being able to address and thereby reframe the power framework of who has the authority to interpret religious texts. This could lead to a fresh medium of expression on matters to do with religious belief and diversity, not only for themselves in their personal lives, but also for others in the community.

The growth of the gendered transnational networks of religion mediated exclusively by, and focused towards and funded by, women’s contributions challenges the way the male elite have traditionally controlled religious spaces in diasporic communities. This could only happen if one applies alternative means of seeing not only the socio-political practices of diasporic communities but also how one views the religious behaviour of the women living in these communities. Though women may explain their religious involvement and social performances as moral obligations and religious responsibilities, in many ways they are challenging the authority of others to define and interpret religious duties for them.

——————

© Aneela Zeb Babar

Excerpt from Chapter:

Excerpt from Chapter: